The Lion In His 75th Winter

Monday, November 26, 2007

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

(With profuse apologies to Robert E. Howard)

Still carven with the heraldry of a dynasty decades gone, the door closed behind his well-wishers, and all at once the walls, ceiling, and floor of the chamber were only a more well-appointed version of the dungeons into which his many captors had flung him. They crowded in upon the king, tightening their grip in much the same fashion, it seemed to him, as would the old age he had held at bay for so long. He listened to the retreating footsteps, footsteps which to his irritation tripped lightly, almost mincingly. The footsteps of men too young to have been at Valkia and Tanasul, too young for the siege of Khorshemish or the foray that caught thirty war-chiefs bickering over Zogar Sag’s old ostrich feathers at Gwawela. The footsteps of those born too late even for the great eastern campaign that had ended with Hyrkanian horsemen gazing in awe across the Vilayet as the night sky was lit by what had been Aghrapur and was now the funeral pyre of Yezdigerd’s ambitions. The footsteps of courtiers and dissemblers.

His stormy nature mutinied against the notion of celebrating his 75th birthday. The feigned merriment of the interlude just past fell away from him like a mask, and his face was suddenly even older than the occasion implied, his eyes clouded. For weeks the inherent melancholy of his ancestral hills had been dampening the dynamism he had always taken for granted, paralyzing him with a crushing sense of the futility of human endeavor and the meaninglessness of life — of his life as it would be told and retold in the far future. His kingship, his pleasures, his fears, his hopes, and all earthly things were revealed to him suddenly as dust and broken toys. He now knew that the borders of the life he had lived would be transgressed, flouted. Dozens of spurious episodes, devoid of either veracity or invention, would diminish him, as if jesters from an alien, frivolous court had been vouchsafed the power to dress him in fool’s motley. Dropping his snow-lion head in his formerly mighty hands, he groaned aloud.

By what weird and winding paths had he wandered into a mind-mist clammier and more all-enveloping, an outlook more draped in darkness and deep night, than even the worst weather to be endured in his dour homeland? Long ago he had told a woman who danced for him like the leaping of a quenchless flame that he sought not beyond death. That state might be the blackness averred by the Nemedian skeptics (some of whom, lured by the king’s far-famed tolerance and his queen’s magnanimous hospitality to her countrymen, now lectured in Tarantia), or Crom’s realm of ice and cloud, or the wintry plains and warrior-welcoming halls of the Nordheimer’s Valhalla. Little had it mattered to him, so long as he could live deep while he lived, relish the rich juices of red meat and stinging wine on his palate, the hot embrace of white arms, the mad exultation of battle when the blue blades flamed and crimsoned. Life but an illusion? Then he was no less so, and being thus, the illusion was real to him.

Illusory or not, life had been a ceaseless battle, a series of battles, since his birth, with death the most constant of companions. It flanked him sociably; stood at his shoulder beside the gaming-tables; beckoned tavern keepers to bring the next round. Its eye sockets watched over him as he took his rest. He had minded its presence no more than a king minds the presence of his cup-bearer (and several of those had tried to poison him at the behest of the Stygians and Turanians). Some day its fleshless grasp would close, and if that day had drawn nearer, what of it? But of late fell dreams had flocked to his bedside, gathering like the vultures waiting for the end when he hung on Constantius’ cross outside Khauran. These dreams taunted with visions of events beyond his death blacker than the skeptics’ nothingness and bleaker than the cheerless eternity of his own people. He was no stranger to fictions in which he was the protagonist; a score of ballads had celebrated the ferocious and audacious exploits from just the piratical chapters of his life, and many poets had looked on the subject matter he offered them with favor, in the days of his wanderings, and in the time of his kingship. With grim humor and, more infrequently, genuine respect, he had attended to the few efforts to refine the raw and riotous into stately epic that men had dared to perform in his presence. Had he not always known that a great poet was greater than any king?

So at first, having been made more of a reader by travels and perils than even those best acquainted with him would have believed a barbarian could be, he had devoured the stories which the recently attendant dreams fetched for him. But lir an mannanan mac lir! These scribblers of a world as strange to him as Andarra, or Tothra, or Kuth of the star-girdle, they were no poets! Although they had the uncannily true-to-life accounts of a single predecessor, to whom the king’s actual words and deeds had been transmitted in mysterious and mystic fashion, to model their imitations on, their tales were populated only by gray groping phantasms, slack-stringed or clumsily jerked puppets. In their battles the combatants bled only wasted ink, and their lissome beauties were no more tangible than the smoke from burning refuse. Oh, he had been permitted a few glimpses of better efforts with the old, true bardic blood in their veins — hair’s-breadth escapes in a version of Kordava dreamed with such detail and so much danger that almost the king could remember a sojourn there, a hunt for the treasure of lost Python south of the Zarkheba, and a wild tale of a monstrous lotus-plant.

But always these exceptions were overwhelmed by so-called adventures like that in which he tarried in Yezud, mooning hopelessly and haplessly over a nondescript temple dancer. Another claimed to chronicle his bid for the throne, but had him disdaining to finish off an abject Numedides with the doltish words, “I do not hunt mice. Tie up this scum until we find a madhouse to confine him.” Still another brought in the very god of the king’s people to save his favorite from a sorcerer of Paikang, with the deity windily declaring “You are a son of Crom, and he will not let you suffer eternal damnation! You have always been true to him in your heart, and the black arts of the East shall not have your soul!” The king was too distraught even to enjoy imagining what would have befallen that particular storyteller had he attempted to regale a Cimmerian audience with his tale.

Still more offensive was a scene in which, as in too many of the supposed annals of his later reign, he was shadowed by a brat whose name was a cloying diminutive of his own (what barbarian ruler of civilized subjects would provoke them so needlessly? His real sons had been given old, proud Aqulonian names), while he indulged in a maudlin reverie about the fallen Thoth-Amon, supposedly thinking, He was the greatest of all the foes I have overcome. I shall miss the old scoundrel, in a way. Recalling the wolfish grin that had in fact played about his lips when the thoroughly bisected and semi-ophidian halves of the Stygian had left off thrashing, the king reflected that most of the tale-weavers betrayed an utter lack of interest in seeking to understand what drove the man whose legend they were purportedly embellishing.

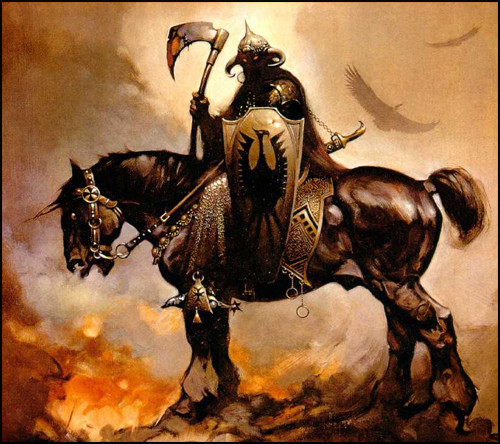

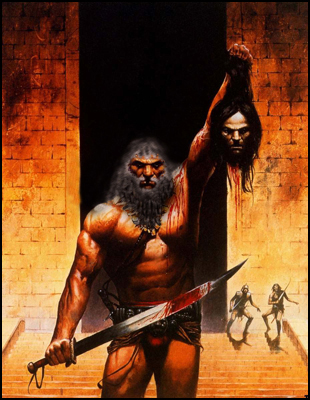

The artists of that age insisted upon rendering him not only witlessly bare-chested, like some stripling who’d never fought in aught else but a midsummer skirmish on the northern marches, but with every last body-hair plucked, a custom favored by Shadizaran she-males in the Deviants Quarter. This travesty was beset in every sketch and painting by monsters as myriad and meaningless as the midges that plague marsh-farers. Worst of all had been a form of tapestry, the images of which moved with a semblance of life, if no pretense of accuracy. Almost immediately infuriated by the slanderous suggestion that a Cimmerian clan would be but a moment’s sword-fodder for southern raiders, the king’s rage had become incandescent when he realized that his youthful self was being impersonated by a mummer with as overdeveloped and artificially maintained a physique as Baal-pteor’s. Slow of movement and dull of wit, this impersonator spoke but haltingly, with an untutored accent closer to that of a manure-mired yokel from Gunderland, or a village idiot in the Border Kingdom’s most backward barony, than a Cimmerian burr. He grew to what apparently passed for manhood while bound to something called a Wheel of Pain, at which he labored with bovine docility. The king had come awake with a cascade of imprecations before the strange tapestry could unfold any more of its sorry excuse for a story.

The dreams had persuaded him that a nightmarish swarm of idiot chroniclers and caricaturists would crawl across his life, obscuring its events. And had it ever been his life at all? Perhaps he had never lived, but only been put through his paces to earn debased coins in a marketplace where poetry’s beauty and power earned yawns or jeers. The king had never submitted to thralldom easily, as the many Hyperboreans he’d sent to their god Bori while still a stripling could have attested. Why should he not cheat those who would enslave an insipid likeness of him by striking out for a realm beyond even death’s gray lands, a place of nonbeing? So the demons who were now his counselors whispered until that night, when, having joined in neither the drinking nor the singing at his own feast, he approached his lordly couch as if it were his newest battlefield. Had Zenobia still been alive and next to him, she would have begged him to desist from running his finger along the edge of an age-old dagger, a royal heirloom looted by the first Aqulonii and reputed to bestow not the gift of surcease but the darker boon of never having existed.

Then it seemed to him that Yag-kosha, or Yogah of Yag, appeared before him, morning-crowned and shining, with wings to fly, and feet to dance, and eyes to see, and hands to point, a Yag-kosha such as the king had only fleetingly glimpsed in the blazing heart of a great jewel. And point that strange being did, to the excruciations of rack and brand with which Yara would have continued to coax his secrets from him, had a bold outlander not scaled the elephant tower. Yogah took the king through the early chapters of his life, showing him Atali’s brothers as they placed many more smoking hearts on Ymir’s board, Bàªlit and her corsairs unavenged, a matter for the madman’s laughter of were-hyenas; Thugra Khotan, Thog and Thaug all abroad in the world for long years, Aram Baksh still supplying fresh viands for palm grove repasts, Yimsha’s lord, the rule of mostly demon-kind having palled, dispatching the Black Seers time and again to hold the gorgeous East in fee; the ebony giants of an isle far out on the Western Ocean gloating over their collection of shrunken and ossified mariner remains; Velitrium ashes dusting the surface of the Thunder River.

And after Yag-kosha there came to the king from the black heart of Mount Golamira the sage Epemitreus: “Said I to you once that your destiny was one with Aquilonia? Feeble was my vision. The womb of Fate is big with your feats, and your destiny is one with the dignity and potential freedom of all who come after. Always will men tell stories of conquerors, but all the more do they need tales of the unconquerable to set against them.” Then Epemitreus showed the king what would have come to pass without him: Arpello of Pellia enjoying a reign briefer but no less calamitous than that of his cousin Numedides, while the Kothians and Ophireans ravened through the streets of Shamar and the fruitful fields of Attalus. Meanwhile the fairest daughters of Aquilonia were whisked to the cellars beneath a citadel of scarlet, the same pits in which hell-rooted Yothga slaked its thirst with Pelias’ soul. But even as he witnessed the dreadful scenes the king was aware that Arpello, the southern invaders, and even Tsotha-lanti were merely jackals and wolves gulping down their paltry meals before the Dragon stooped to his meat.

As if sensing this Epemitreus now displayed the Dragon’s Hour, an Hour that would endure for millennia, the triumph of Fear and Night. The priests of Asura and the priests of Mitra found a fellowship at last, in the equally ghastly dooms that befell them. There being no fools like cunning fools, Orastes and Amalric and Valerius and Tarascus died during the early days, died cursing their folly for attempting to saddle and bridle the Dragon. Then the dark, long-memoried folk of mountain villages shunned by other Nemedians began to stir, as their revenant priest-king thaumaturgically reshaped the dust of three thousand years. The physical features of the Hyborian kingdoms wavered, as if doubting their own solidity, while the purple towers of yester-age shimmered at the edges of sight. Blood sluiced away the vestiges of reality and the red Acheronian tide rolled in unstoppably, cresting like the waves that drank the cities of long ago. And the present was swept away by a future that would only ever be the past dreamed by the Dragon.

Epemitreus looked expectantly at the king, who shook his gray-and-white mane and grinned a trifle sheepishly. The dagger lay discarded in a corner. Macha and Nemain, but his life had meant something, had not only left its mark on the world but thwarted others who would have marked it far more terribly! Things and happenings assumed new values. The worthless babble of uncomprehending chroniclers faded and failed. He stretched himself in a manner more catlike and less cautious than had been the case for years, and seated himself at a work-table, conscious of the magnitude and vital importance of himself and his remaining tasks.

Happy 75th birthday, old friend!