Owchar Reviews The Return of the Sorcerer

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

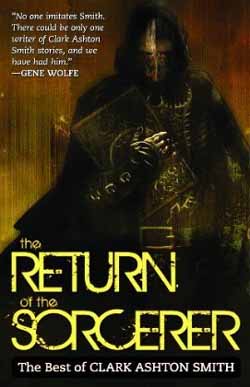

Last weekend, Nick Owchar reviewed The Return of the Sorcerer for The LA Times. The book itself is a new “best of” collection featuring the tales of Clark Ashton Smith and is published by Prime Books.

Last weekend, Nick Owchar reviewed The Return of the Sorcerer for The LA Times. The book itself is a new “best of” collection featuring the tales of Clark Ashton Smith and is published by Prime Books.

Owchar starts out well enough, noting that the “Weird Tales Circle” does not get near the attention it should from mainstream literary critics. I agree. Umpteen tomes have been published going on about the “Bloomsbury Group,” whilst the inferno of synergistic creativity that blazed around the core members of the “Weird Tales Circle” goes largely unexamined. As Leo Grin stated four years ago, “someday a book combining the lives of all three Weird Tales geniuses — Howard, Lovecraft, and Smith — will have to be written.”

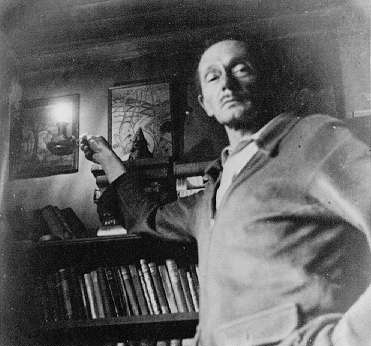

Mr. Owchar proceeds to quote a bit from what sounds like a solid introduction by CAS (and REH and HPL) fan, Gene Wolfe. Owchar calls Smith “an overlooked master of a wholly original vein of horror and hallucinatory science fiction,” while also noting CAS’s endeavors in the fields of poetry as well as the graphic and sculptural arts. Towards the end of his review, he expresses a deep admiration for Smith’s work and a hope that Klarkash-Ton’s oeuvre will soon achieve the recognition it so richly deserves.

Beyond the positive points noted above, I think Nick Owchar’s review suffers from some serious problems.

The paragraph that Owchar devotes to a quick overview of Smith’s life is riddled with errors and half-truths. He alludes to CAS dealing with “mental issues” in his youth. While Clark appears to have suffered depression from time to time, I’m not sure the mention was necessary. Smith definitely experienced long-term physical after-effects from a bout of scarlet fever contracted as a child, as well as battling what may have been tuberculosis (the diagnosis is still unclear) for several years.

The paragraph that Owchar devotes to a quick overview of Smith’s life is riddled with errors and half-truths. He alludes to CAS dealing with “mental issues” in his youth. While Clark appears to have suffered depression from time to time, I’m not sure the mention was necessary. Smith definitely experienced long-term physical after-effects from a bout of scarlet fever contracted as a child, as well as battling what may have been tuberculosis (the diagnosis is still unclear) for several years.

Owchar then states that “Smith settled in a cabin not far from Auburn.” Directly following the “mental issues” sentence, that statement might lead one to believe that CAS had fled to the wilderness in an attempt to escape from society; a sort of proto-Kaczynski or McCandless. In simple fact, Clark moved there with his parents when he was about nine years old.

It is then stated that Clark Ashton Smith stopped writing fiction completely in 1935. This is patently false. While his prose output dwindled to about one story every two years following the death of his father in 1937, Clark Ashton Smith did continue writing fiction. Smith had little incentive to do so following the death of both his parents (who depended on his income), especially in the ’40s and ’50s, which were hard times for virtually every weird fictioneer in the field. I recommend Allan Gullette’s short biography of CAS for those wanting a succinct, accurate and accessible picture of Mr. Smith’s long life.

Referring to the initial (and eponymous) story in the collection, the LA Times reviewer claims that it “reads like a Lovecraft clone.” Perhaps Mr. Owchar is unaware of the fact that “The Return of the Sorcerer” was written in fairly close collaboration with HPL. During January of 1931, the two giants of fantasy batted plot ideas for that tale back and forth in their letters. It comes by its cachet of Arkham-ness with all honesty and legitimacy. Lovecraft and REH both loved it, and “The Return of the Sorcerer” remains one of Smith’s most popular tales (thus its inclusion in this collection), if not one of his most characteristically “Klarkash-Tonian.”

Owchar extends this “Lovecraft clone” business to Smith’s stone-cold classic, “The City of the Singing Flame,” calling it “a pale tribute to Lovecraft’s ‘Call of Cthulhu.’ ” I just don’t know what to say to that. Somehow, this insight was denied to authors and critics as perspicacious as Harlan Ellison, Ray Bradbury and Tim Powers (not to mention HPL himself). If anything, the story strikes me as a soaring, ground-breaking tribute to some of the works of A. Merritt, an author whom we know CAS admired.

The reviewer ends the essay by noting that Smith’s tales are “intriguing,” and possess “unexpected narrative turns.” He vitiates this praise, in my opinion, by calling Clark Ashton Smith’s prose “reckless and messy.” Every scrap of data we have to hand indicates that CAS was a meticulous word-smith, one who would go through several drafts of a tale, reading each aloud in the haunted hills above Auburn. Smith was a poet praised by his peers as a genius from the time he was a teenager. Reckless and messy? He was not. Vibrant, experimental, vivid, self-assured? Yes, he was.

DEUCE ADDS: Mr. Owchar was kind (and assiduous) enough to append a postscript to his review acknowledging that some of his facts might not have been as accurate as he would have liked. As veteran readers of TC may know, Nick Owchar wrote a well-researched essay regarding Solomon Kane.