Sailing With the Sea Kings of Mars: Brackett’s The Sword of Rhiannon

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

Erik Mona and Planet Stories pulled off a sweet commemoration of a diamond jubilee this last June with their reprinting of The Sword of Rhiannon. It was in the June 1949 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories that Leigh Brackett’s, “The Sea Kings of Mars,” first appeared. With Brackett’s approval, that tale has been reprinted with the title of The Sword of Rhiannon ever since (or nearly so).

Beginning with the Ace Double that featured Conan the Conqueror on the flip-side, nearly all subsequent printings of Brackett’s novel sported The Sword of Rhiannon as the title. Simple (socio-) economics. As Leigh noted in her afterword to The Best of Leigh Brackett, post-war editors were getting more leery of publishing her type of ERB-influenced tales; tales where the Red Planet supported an ancient, humanoid population amidst which Earthmen found adventure. This was due to the (at the time) recent (and dream-shattering) advances in the sciences. Apparently, faster-than-light drives were more “real” than the possibility of life on Mars (though the opposite seems just as likely today). Renaming this story “The Sword of Rhiannon” allowed a better chance of an unwitting (and lucky) reader picking up the book and then getting pulled in by Brackett’s hard-boiled, Howardian prose. The fact that Leigh persisted in writing later tales like “The Secret of Sinharat” and “The People of the Talisman” is a testament to her authorial courage and passion for the Martian “sword-and-planet” sub-genre.

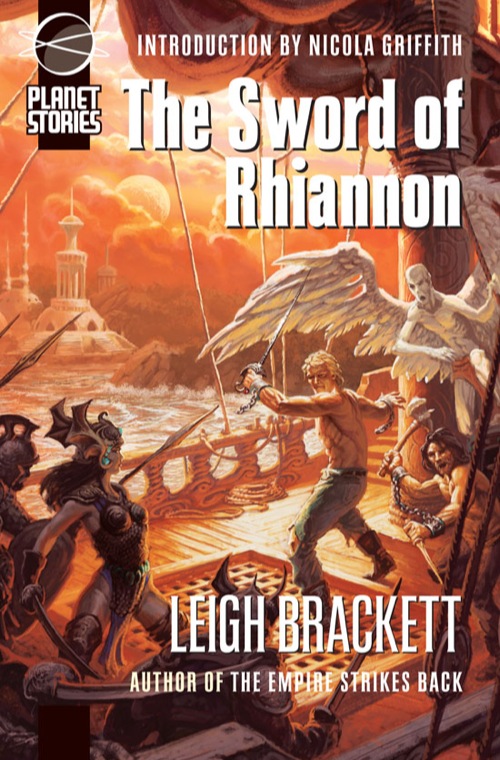

Paizo’s new reprinting of The Sword of Rhiannon is the best showcase for this novel thus far assayed, in my opinion. The cover by Daren Bader is well-wrought and action-packed. Nicola Griffith’s introduction, while quite thoughtful and appreciated by yours truly, could have been a bit better, perhaps. Then again, that leaves room for the tossing-in of my two coppers, doesn’t it? On with the tale…

Brackett sets her stage in the Low-Canal Martian town of Jekkara, a spiritual sister-city of Robert E. Howard’s Zamora, the City of Thieves.

Carse walked beside the still black waters in their ancient channel, cut in the dead sea-bottom. He watched the dry wind shake the torches that never went out and listened to the broken music of the harps that were never stilled. Lean lithe men and women passed him in the shadowy streets, silent as cats except for the chime and whisper of the tiny bells the women wear, a sound delicate as rain, the distillate of all the sweet wickedness of the world.

Matthew Carse himself, a space-brat raised on Mars, a defrocked planetary archaeologist-turned-thief, is limned in these terms:

The little thief stared in impotent rage at Carse, standing tall in the lamp glow with the sword in his hands, his cloak falling from his naked shoulders, his collar and belt of jewels looted from a dead king flaring. There was no softness in Carse, no relenting. The deserts and suns of Mars, the cold and the heat and the hunger of them, had flayed away all but the bone and the iron sinew.

A bit later, Carse’s thievish Low-Canaller guide, Penkawr, waxes rebellious:

He turned and fixed Carse with a sulky yellow stare. “I found it,” he repeated. “I still don’t see why I should give you the lion’s share.”

“Because I’m the lion,” said Carse cheerfully.

I dare anyone to dispute that Leigh Brackett had read Robert E. Howard and was influenced thereby. Actually, I’ll save you the trouble. She said so on several occasions, and in The Sword of Rhiannon she proves what an apt pupil she was.

Carse soon undergoes a transcendent experience rivaling anything in “Queen of the Black Coast” or “Marchers of Valhalla.” Thereafter, he finds himself back in Jekkara, where he meets Boghaz of Valkis. Boghaz is a light-fingered step-child of Mundy’s Chullunder Ghose and a Dutch uncle to Glen Cook’s Mocker; a silver-tongued, Falstaffian thief with a heart of debased gold.

The twain quickly find themselves shackled to an oar aboard the galley of the PrincessYwain of Sark. Partaking of aspects of REH’s Belit, Moore’s Jirel and Merritt’s Sharane, Ywain is described in this manner:

She stood like a dark flame in a nimbus of sunset light. Her habit was that of a young warrior, a hauberk of black mail over a short purple tunic, with a jeweled dragon coiling on the curve of her mailed breast and a short sword at her side.

Later in the novel, Ywain says of herself that, “My father Garach fashioned me as I am. A weakling with no son — someone had to carry the sword while he toyed with the scepter.”

King Garach maintains his hegemony over half of Mars due to his alliance with Caer Dhu. The Dhuvians are few in number, but possess fearsome powers, powers they use to aid and intimidate their pawn who sits the throne of Sark. When the shadow kings of Mars reveal themselves to Carse, one can feel the ghost of Robert E. Howard at Brackett’s shoulder…

Sinuous bodies that moved with effortless ease, seeming to flow rather than step. Hands with supple jointless fingers and feet that made no sound and lipless mouths that seemed to always open on silent laughter, infinitely cruel. And all through that vast place whispered a dry harsh rustling, the light friction of skin that had lost its primary scales but not its serpentine roughness.

The Sword of Rhiannon is not Brackett’s “sword-and-planet” masterwork. In my opinion, that would be her “Book of Skaith” trilogy (also recently published by Planet Stories/Paizo). Leigh hadn’t been in the writing game quite a full decade when she penned The Sword of Rhiannon and was yet to come into her full powers as an author. That said, Brackett had obviously found her own voice at that point, assimilating her influences and carving out her queendom in the science-fantasy field. The Sword of Rhiannon moves at a relentless pace and is filled to the brim with plot-twists and reversals of fortune. Carse is a “damaged hero” in the classic Brackett mold who hews and schemes his way across a gorgeously-imagined world. The Sword of Rhiannon was a milestone in Leigh Brackett’s career and is a novel well worth reading today.

found her own voice at that point, assimilating her influences and carving out her queendom in the science-fantasy field. The Sword of Rhiannon moves at a relentless pace and is filled to the brim with plot-twists and reversals of fortune. Carse is a “damaged hero” in the classic Brackett mold who hews and schemes his way across a gorgeously-imagined world. The Sword of Rhiannon was a milestone in Leigh Brackett’s career and is a novel well worth reading today.