Three friends of The Cimmerian in the news

Wednesday, March 18, 2009

posted by Leo Grin

Print This Post

Print This Post

Don Herron’s The Dashiell Hammett Tour: Thirtieth Anniversary Guidebook is released

Don Herron is the best critic in Howard studies, bar none. However, REH is but a small part of his professional output. He’s most famous for helming the longest-running literary walking tour in the US, San Francisco’s Dashiell Hammett Tour. Over three decades it has become a Bay Area institution and a must-do for mystery fans and literati alike. In 1991 City Lights, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s legendary counterculture imprint, published Don’s The Dashiell Hammett Tour: A Guidebook, which garnered great reviews and has been much sought after on the used market, often selling for over $100 in fine condition.

Now, Don has released a brand new, fully revised and updated version of his book. Published by Vince Emery as a part of his Ace Performer Collection, a group of titles by and about Hammett, this new edition looks beautiful, and is in hardcover to boot. Don has been running around doing various appearances in support of the release — just in the last few weeks he hit Boise, Idaho; Tuscon and Scottsdale, Arizona; and a bunch of places in and around San Francisco. MSNBC has a write-up of the book’s contents and of Don’s future book signings in the Bay Area. You can also keep up with the action at his website.

All of Don’s books are well worth hunting down — he’s collected, in fact, by the prestigious Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, an organization that calls him on their website “the godfather of San Francisco mysteries.” But The Dashiell Hammett Tour book occupies a special place in his canon. The tour has been written up hundreds of times in virtually every major newspaper and venue, making it one of the most popular of its kind in the world. It (and Don) even appeared as an answer/question combo on Jeopardy! once. (To bring a bit of Cimmerian flavor into all of this: Don found out about the Jeopardy! thing when his good pal, the fantasy writer Fritz Leiber, called him up with the info. Leiber was a Jeopardy! fiend in his later years and caught wind of the Herron appearance during his usual afternoon viewing.)

So if you are a Hammett fan, or a fan of great literature in general — pick up a copy of the book at Amazon or wherever fine mystery books are sold.

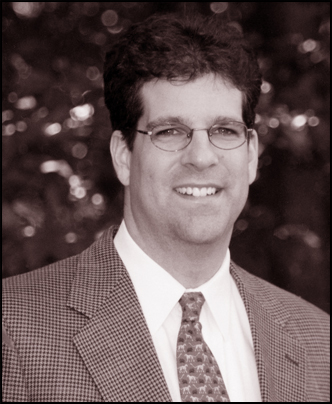

John J. Miller on Charles Dickens in The Wall Street Journal

John J. Miller has been the single best friend of Robert E. Howard studies in the mainstream media over the last few years. He’s written about REH in The Wall Street Journal, interviewed Rusty Burke for National Review Online, and covered Paul Sammon’s Conan the Phenomenon on his Between the Covers podcast interview series. All of these were fair-minded pieces that seemed to go above and beyond in the attempt to get the facts straight, and each offered valuable assessments of the guy whose literary output inspired The Cimmerian in the first place. And hey, as anyone who is politically minded knows, fighting the good fight in popular culture often means absorbing a few punches, like this one from a blog called The Mystery of the Haunted Vampire:

Finally a National Review writer pens a column I agree with. From The Wall Street Journal:

The Conan stories make up only a small fraction of this huge output: There are 21 of them, including a novel, and they were written at breakneck speed between 1932 and 1935. As with everything by Howard, their quality varies dramatically: A fantasy classic such as “Beyond the Black River” remains a riveting tale that undermines popular notions of frontier progress and manifest destiny; “The Vale of Lost Women,” however, is a clunky piece of hackwork that would be instantly forgotten were it not for the fame of its star character.

Yet the stories share a fundamental power because Howard was a skilled action-adventure storyteller. So were a lot of other pulp writers, of course. What ultimately set Howard apart was a dazzling imagination that dreamed up the sword-and-sorcery subgenre of fantasy literature before anybody had heard about J.R.R. Tolkien and his hobbits.

With Conan, Howard created a protagonist whose name is almost as familiar as Tarzan’s. In his influential essay on Howard, Don Herron credits the Texan with begetting the “hard-boiled” epic hero, and doing for fantasy what Dashiell Hammett did for detective fiction. Suddenly, the world — even a make-believe one such as Conan’s Hyboria — was rendered seamier and more violent, and Howard described it in spare rather than lush prose.

Interesting how John J. Miller never mentions that Conan overthrew a tyrannical ruler. I guess when you have a history of surrendering your freedoms to the whims of a despot like Miller and his colleagues at the National Review do, you don’t want to point out when heroes fight for their liberty. Or perhaps that is the answer there: Conan fought for the causes he believed in. The chickenhawk hacks at the National Review want others to fight their fights for them.

Talk about taking one for the team! (and wait until our own Steve Tompkins notices that Conan’s world is called Hyboria in the article, a term Steve ranted about to great effect here).

At the same time John has been promoting the Howardian cause in various venues, he’s also been writing about a staggering number of other fantasists, mystery writers, sci-fi novelists, and horror mavens: H. P. Lovecraft here, Tolkien here, C. S. Lewis here, here, here, and here, Russell Kirk here, Dr. Seuss here, Dungeons & Dragons here, Jules Verne here, Arthur Machen here, Beowulf here (and the animated Beowulf movie here), David Gemmell here, Arthur C. Clarke here, Ernest Hemingway here, Dracula here, Michael Crichton here, Edgar Allen Poe here. And let’s not forget the podcast interviews: George R.R. Martin here, Dean Koontz here, Otto Penzler and his Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps here, John Rateliff’s The History of the Hobbit here, David Anderegg’s book about nerds here, Ursula K. Le Guin here, Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia here, Harry Turtledove here, Anne Rice here, Joseph Pearce on Frankenstein here, Orson Scott Card here, Kevin O’Brien on Howard favorite G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown series here, T. Jefferson Parker on In the Shadow of the Master: Classic Tales by Edgar Allan Poe here. New Cimmerian blogger (and inveterate headbanger) Brian Murphy will appreciate John’s take on Brian’s favorite metal band, Iron Maiden. And there’s even a charming little piece online about what John told an assembly at his kids’ school about being a writer.

Other fandoms would kill to have someone in the mainstream media slugging away on their behalf who was half as prolific or generous as John has been to Howard. His latest published piece is on the great unfinished novel of Charles Dickens, The Mystery of Edwin Drood — you can read his take on the whole business here. Keep your eyes peeled for John’s byline — wherever it appears, good genre and pop culture writing will be waiting for you.

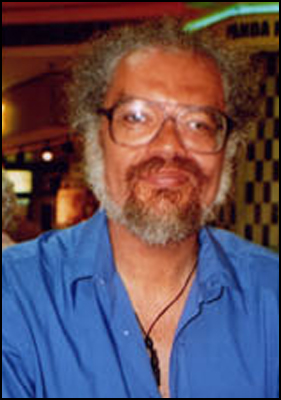

Charles R. Saunders’ The Trail of Bohu released

We’ve already covered this here at TC, both here and here. But it certainly bears repeating: If you’ve never experienced what our good friend Charles has dubbed “Sword & Soul,” then you’re missing out on one of the great achievements in fantasy, especially in the crafts of worldbuilding and subcreation. That a reputable mainstream publisher hasn’t long ago bought up all five of the Imaro novels (the last two of which have yet to see print) and published them in an omnibus edition should be a source of acute shame throughout the industry. Ditto the failure of Afro-centric media outlets — publishing imprints, magazines, TV and online media — to herald one of the absolute pioneers in the field of African-American fantasy, stories written by an African-American and for everybody. Cimmerian website manager Steve Tompkins once told me that he considered Saunders “the Walter Mosley of fantasy,” and anyone who has read Mosley’s Easy Rawlins series or his brooding novels about Socrates Fortlow will get where he is coming from.

In a field where all sorts of forgettable multi-volume doorstops get printed each year to little fanfare and even smaller sales, it astounds me that publishers aren’t leaping at the chance to grab a series that is as original as anything you can find on the shelves, yet one that has strong connections with classics like Howard’s Conan. Saunders’ prehistoric, magic-filled, fantasticated Africa brims with inventiveness and adventure. The world feels incredibly authentic and lived-in due to Charles’ use of his large amount of obscure yet compelling research into real-life African civilizations. Names, customs, spells, religion, wars, cultures — all are filtered through an imagination forged by the classics, the pulps, and the S&S fiction of the 1960s and ’70s. What emerges is one of the great fantasy worlds: Nyumbani, an Africa seen through a glass brilliantly, where magic and swordplay and love and hate all blend into a powerful brew as compelling in its sheer breadth and depth as Middle-earth and The Hyborian Age.

And yet, like all great fantasy, there is always so much else rumbling between the lines of Saunders’ stories, always some thematic undercurrent touching on questions of belonging, questing, faith, race, friendship — the Soul that goes hand-in-hand with the Sword. Those who have drunk deeply from Charles’ nonfiction — “Die Black Dog! A Look at Racism in Fantasy,” “Of Chocolate-Covered Conans and Pompous Pygmies,” Sweat and Soul: The Saga of Black Boxers from the Halifax Forum to Caesars Palace, “Why Blacks Don’t Read Science Fiction,” “Why Blacks Should Read Science Fiction,” et al. — can acutely appreciate all of the subtext and self-awareness that was poured into these tales. In the context of critical and cultural depth, it could be said that the Imaro and Dossouye stories are some of the most important ever written in the field of fantasy. Charles Saunders was the first black writer to tackle Sword-and-Sorcery head-on, confronting all of the cultural and racial baggage dragged along with the subgenre since its public debut in the August, 1929 Weird Tales. The balancing act he achieves between championing the genre’s strengths while simultaneously crushing its weaknesses and prejudices remains unequaled over three decades after the first Imaro story saw print.

Steve Tompkins did an excellent, must-read interview with Saunders in The Cimmerian V4n5 (October, 2007), wherein many of the nuances of Saunders’ artistry are explored. Here’s the introduction to that interview, which gives a good capsule overview of what makes Charles’ writing so significant to those of us who follow the history of the field, and who haven’t forgotten the past (or given up hope for the future):

Charles R. Saunders has done as much for Howard’s legacy by demonstrating what else the Howardian subgenre of Sword-and-Sorcery can do as he has by writing numerous articles about REH characters and concepts. Nobel laureate Toni Morrison is one of many to note the past availability of an “accommodatingly mute, conveniently blank” Africa for a variety of popular culture purposes: “It could stand back as scenery for any exploit or leap forward and obsess itself with the ways of any foreigner; it could contort itself into frightening malignant shapes…or it could kneel and accept elementary lessons from its betters.” Within heroic fantasy it was Saunders who called a halt to all this, who insisted on an Africa for the Africans, as dreamed by an African-American. His Nyumbani is an iridescent, many-cultured mosaic of the lost but real kingdoms of Africa, shadowed by sorcery, bloodied by the wars and banditry to be expected wherever human beings coalesce as peoples and polities, and stalked by the barbarian warrior Imaro, a direct descendant of Conan in his indestructibility and uncontrollability. Imaro’s fame soon rivaled that of Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane in ’70s/’80s semiprozines like Dragonbane, Phantasy Digest, Dark Fantasy, Fantasy Crossroads, Space and Time, The Diversifier, and Weirdbook, and Saunders became a standout in anthology after anthology: The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories, The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories 3, Swords Against Darkness IV, Heroic Fantasy, Hecate’s Cauldron, Amazons!, Sword & Sorceress. Finally DAW Books gave him the chance to shape Imaro’s early adventures into the novels Imaro and Imaro II: The Quest for Cush; the all-new, and escalatingly epic Imaro III: The Trail of Bohu followed in 1985. But 1981’s Imaro was hobbled by litigation-inviting cover copy (“The epic novel of a black Tarzan”) that forced a recall of the first batch printed, a pill made more bitter because Saunders envisioned his hero not as a Lord Greystoke in blackface but as “the brother I always wished would show up and kick Tarzan’s ass.”

The three novels thrilled almost everyone who read them, but not enough people did for DAW to publish the fourth and fifth books. In 2006 Night Shade Books revived, and Saunders revised, the series, to the great joy of those who remembered the ’80s novels. However, mere months after the 2007 release of the new-and-improved The Quest for Cush, it was dispiriting déjàvu all over again; forget about the fourth and fifth novels, Night Shade was going to deny us even the third. But hope springs eternal (and also pantherishly); Imaro is as difficult to kill off the printed page as he is on it, and stratagems for his survival — as well as various Howardian topics — all featured in my recent interview with Saunders.

The failure of the published Imaro novels to gain traction in the marketplace had far more to do with the missteps and shoddy marketing of their respective publishers than any deficiency in the books themselves. It always amazes me that award-winning publishers can, under the fog of their own high self-regard, be such brazen incompetents. Take the most recent publisher of the first two Imaro books, Night Shade Books. Five years ago I gave them a major chunk of change for their five-volume series of William Hope Hodgson stories, and to this day the last volume has yet to appear, despite their releasing many other books each year. If it takes them a half-decade to get out a book of public domain stories, what hope did poor Saunders ever have with them? But after being burned twice, Saunders has taken matters into his own hands, and is now getting the Imaro and Dossouye books out in nice trade paper editions from Brother Uraeus’ Sword & Soul Media publishing imprint. Imaro has a small but dedicated fan base that has been (in some unfortunate cases) literally dying for the rest of the Imaro books to finally appear. Any way that we can get them, we’ll take them.

But I do sincerely wish that some enterprising East Coast publisher would at long last get on the ball and see what a gem they could have in Imaro, Dossouye, and Saunders. With the right marketing, the series could become a hot seller not just to the Walter Mosley reading public, but to fantasy fans in general. I’m confident that’s going to occur someday — the cream always rises eventually — but I hope it doesn’t happen too late to do Charles any good, the way it did for guys like Howard and Lovecraft back in the day. Oh well, if Sword & Soul Media can get the last two Imaro books out by the end of this year, then Saunders can get cracking on his next novel, one that might click with Tor or Del Rey or Pyr, someone of that ilk. Until then, you can still get the first two Imaro Books, Imaro and The Quest for Cush, from Night Shade, and the third, The Trail of Bohu, from Sword & Soul Media. You can also get the first Dossouye collection from Sword & Soul Media. That site references Saunders as the “critically acclaimed author of the cult classic Imaro novels” — “cult classic” is a description that sounds just about right. May his cult ever grow.