Laying Down The [First] Law

Thursday, October 9, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

It was cased all in bright armour sealed with heavy rivets, a round helmet clamped over the top half of its skull, eyes glinting beyond a thin slot. It grunted and snorted, sounds loud as a bull, iron-booted feet thudding on the stone as it thundered forwards, a massive axe in its iron-gloved hands. A giant among Shanka. Or some new thing, made from iron and flesh, down here in the darkness.

Its axe curved in a shining arc and the Bloody-Nine rolled away from it, the heavy blade crashing into the ground and sending out a shower of fragments. It roared at him again, maw opening wide under its slotted visor, a cloud of spit hissing from its hanging mouth. The Bloody-Nine faded back, shifting and dancing with the shifting shadows and the dancing flames.

That Frazetta-grade dream of a red meeting is from Joe Abercrombie’s 2007 novel Before They Are Hanged, and so is this one:

He came on closer, this shadow, and he took on more shape, and more, and the clearer he got, the worse grew the fear.

He’d been long and far, the Dogman, all over the North, but he’d never seen so strange and unnatural a thing as this giant. One half of him was covered in great plates of black armour — studded and bolted, beaten and pointed, spiked and hammered and twisted metal. The other half was mostly bare, apart from the straps and belts and buckles that held the armour on. Bare foot, bare arm, bare chest, all bulging out with ugly slabs and cords of muscle. A mask was on his face, a mask of scarred black iron.

He came on closer, and he rose from the mist, and the Dogman saw the giant’s skin was painted. Marked blue with tiny letters. Scrawled across with writing, every inch of him. No weapon, but he was no less terrible for that. He was more, if anything. He scorned to carry one, even on a battlefield.

In the two-years-plus since we lost David Gemmell at an intolerably early age, nothing, absolutely nothing, has so reassured me about the future of heroic fantasy as Abercrombie’s sequence The First Law: The Blade Itself (2006), Before They Are Hanged (2007), and Last Argument of Kings (2008). All 3 white-knucklers are now available in the U. S. from the Pyr imprint of Prometheus Books.

The Blade Itself is 527 pages long in the Pyr edition, Before They Are Hanged 537 pages, and Last Argument of Kings, 636 pages. Pagecounts like those will be a turnoff for some potential readers; I sorrowfully picture the estimable Howard Andrew Jones vanishing into the vastness of the steppes as fast as his Cossack steed can carry him. My own opinion is that Abercrombie earns every one of his pages. Yes, sword-and-sorcery does extraordinarily well for itself in novelettes and novellas, but the industry is about as receptive to those formats as to an expanded version of The Satanic Verses illustrated with those Danish cartoons that went over so well in the Dar al-Islam. And although the subgenre’s canonical novels, books like The Hour of the Dragon, The Broken Sword, Swords of Lankhmar, Stormbringer, Darkness Weaves, and Morningstar are seldom of the thick-as-a-brick persuasion, longer novels can acquire a cumulative power by revealing the ultimate fate or innermost essence of characters with whom we’ve spent many hundreds of pages. When we’re lucky breadth and depth back length‘s play.

I’m avoiding the word trilogy in connection with The First Law not only because the term has become such a punchline in any discussion of fantasy as a publishing pheenom, but also because I don’t think Abercrombie wrote one. He might not have pulled a Tolkien by writing one long novel in its entirety before delivering any of it to his publisher, but that’s what his story reads like: one long-and-proud-of-it novel. Putting down The Blade Itself and picking up Before They Are Hanged is now no bigger a deal than turning the page to the next chapter, but it must have been frustrating for those first readers back in 2006 (2007 Stateside) when no “next chapter” could be had. For its part Publisher’s Weekly chose to rain on the parade that was only just getting underway:

British newcomer Abercrombie fills his muddled sword-and-sorcery series opener with black humor and reluctant heroes … The workmanlike plot, marred by repetitive writing and an excess of torture and pain, is given over to introducing the mostly unlikable characters, only to send them off on separate paths in preparation for the next volume’s adventures.

Other complainants faulted The Blade Itself for being short on both disclosure and just plain closure; Abercrombie has responded by invoking the same august predecessor I did:

The Lord of the Rings, surely the sun around which all epic fantasy orbits, makes little effort to wrap up its individual books on anything more than a relatively important moment. No one ever seems to criticise Fellowship of the Ring for leaving a lot of threads dangling. Perhaps that is the key thing about long arcs. They can be frustrating while readers drum their fingers waiting for the next installment, but once the series stands complete, and the reader can just go and get the next one off the shelf (providing the author didn’t make a balls-up of the ending) such issues are soon forgotten.

Now that the one fell swoop approach is possible with their purchase and perusal, the three books of The First Law give readers the opportunity to watch Abercrombie’s story shed its puppy-fat and baby teeth while improving its hand-eye coordination to lethal effect. After a slam-bang opening, long stretches of The Blade Itself are given over to hithering and thithering, but one never suspects authorial dithering. Sure, some patience is required as pawns, knights, and bishops are maneuvered into position on a chessboard that overarches several continents, but Tad Williams’ The Dragonbone Chair and R. Scott Bakker’s The Darkness That Comes Before required more, nor does The Blade Itself leave readers feeling blindfolded, disoriented, and severely impaired by short-term memory loss, as is the case with a few too many chapters of Gardens of the Moon before Steven Erikson’s dramatic improvement in Deadhouse Gates.

We shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but as soon as we’ve finished judging said book by its contents, the cover then becomes fair game. Abercrombie’s publishers clearly wanted no part of the Ken Kellyisms, so tired as to seem to suffer from sleep apnea, of the current Cosmos Books REH paperbacks, or the Fabio-goes-to-war happy-crappy of Tor’s hardcover crimes against Erikson. Instead, they’ve seized a visual identity all their own by going with “grip-friendly” paper with a “burned surround” and a screw-conformity nonrepresentational design suggestive of court documents captured by illiterate barbarians, not so much well-thumbed as ill-used, crumpled, slashed, charred, and bled-upon.

Such covers proclaim in a low growl that the reaver’s torch has been passed to a new generation. Abercrombie was born, in Lancaster, in 1974, the year Marvel launched The Savage Sword of Conan and Michael Moorcock finished off Corum with The Sword and the Stallion. So he was 10 in 1984, the year of Legend and an essay that now seems to create a context for his eventual arrival, George Knight’s Hardboiled Heroic Fantasist” in The Dark Barbarian. He was 20 in 1994, the year “child of mountains” Karl Edward Wagner went forever into night, and 22 in 1996, the year George R. R. Martin made an impact on epic fantasy like Grond battering down the gates of Minas Tirith — Abercrombie has confided that “. . .in terms of influences from written fantasy, between ’93 and ’02, Game of Thrones (and A Song of Ice and Fire in general) is definitely the outstanding (if not the only significant) one.”

But this young writer’s influences unsurprisingly extend far beyond usual-suspect rows of Ballantine, Bantam, or Gollancz paperbacks. Challenged by the SFRevu site with “the old ‘elevator pitch to a movie producer scenario’ in which you must explain your trilogy in a sentence or two,” Abercrombie rocked that imaginary elevator: “Imagine if Tarantino had made Lord of the Rings. Imagine Conan the Barbarian with the self-awareness of Unforgiven. Imagine LA Confidential . . . with swords.” Elsewhere in the same interview, he said of James Ellroy, “I particularly admire the tightness of prose and plot, the brutality and unflinching realism, the skull-popping surprises, the messiness of real life, the loose ends and the sour resolutions. No one’s a hero or a villain, they’re just varying kinds of scum.”

He elaborates on his multimedia influences in a blog-entry:

I read quite a bit of noir and crime, particularly James Ellroy, which taught me some good lessons about hard-hitting prose and twisty plotting. I worked as a documentary editor which gave me some understanding of how to construct a narrative, of how to streamline and cut down (says the writer of enormous 200,000 word books, but hey, I like to think they’re pretty tight). I watched a lot of interesting films, including Tarantino’s stuff (Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction had strong effects on me), John Woo and manga, the list is endless (well, not actually endless, but bloody long). TV changed, I think, in this period, starting to throw up some really interesting series which were shifting media in general in a more realistic, complicated, ruthless direction – stuff like The Sopranos, The Shield, 24 (at least to begin with), Band of Brothers, and later Deadwood, Nip/Tuck and The Wire (man, I love The Wire) – a movement that seems to be creeping into SF TV now with shows like Heroes and Battlestar Galactica. All of that settled on me as well, I’m sure, and I think my approach to action writing probably owes more to what I’ve watched than what I’ve read.

At this late date anyone conversant with teevee criticism might be sick of being told that The Wire is the finest work ever done on American television, but as they would say on the show, the game is the game. Across 5 seasons David Simon and his noir-head dream team (writers like Richard Price, George Pelecanos, and Dennis Lehane) delivered a panoptic, and in a sense postapocalyptic, study of cutthroat politicking and statistics-massaging crimefighting with the remaining resources of a deindustrialized, revenue-starved American city at stake. The Wire is detectible in Abercrombie’s work by way of mean streets the mercilessness of which reach deep into the unpaved countryside from the city of Adua, capital of the Union, the central (and therefore hard-pressed on two fronts) geopolitical entity of The First Law. Feudalism is on the way out and capitalism is on the way in; both naturally step all over humanism. The Inquisition’s Arch Lector Sult, for whom existence is a zero-sum gaming exercise, schemes to be the power behind the throne, and the altar, and the teller’s window, even if he does sneer about “Bankers, shopkeepers, salesmen. Little men, with little minds and little ambitions. Men whose only loyalty is to themselves, whose only duty is to their own purses, whose only pride is in swindling their betters, whose only honour is weighed out in silver coin.”

Noir-ish is not only the seemingly species-wide corruption but the search for The Seed, “a rock from the world below” or “the Other Side made flesh.” When this super-weapon is finally used, the neighborhood-leveling, fallout, and radiation sickness are a reminder of what Nicholas Christopher wrote in his Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City (1997): “Noir not only traces its roots to the dawn of the Atomic Age, but also displays an ongoing obsession with all things nuclear.”

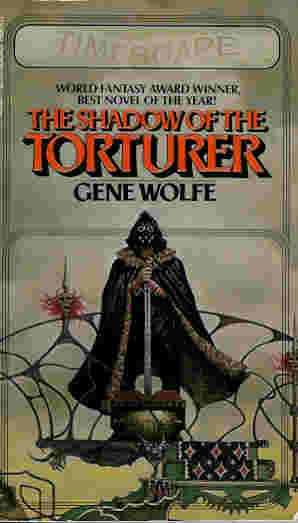

Of The First Law‘s antiheroine Ardee Abercrombie has explained “She’s intended to be a passive-aggressive, self-destructive, manipulative drunk with a sharp sense of humour. I guess that’s not necessarily endearing, and you’re always taking a risk when you work with characters that are heavily flawed or unsympathetic. But part of the approach with these books was to see how dark I could make the characters and still involve the reader with them.” The answer turns out to be pretty damn dark, although I’m beginning to suspect that, over a decade after Martin’s A Game of Thrones plunged into the mire with the precision of an Olympic gold medalist diver,it’s time to retire or at least furlough the descriptions dark and gritty. Too many opportunists are trying too hard to create and chronicle what Dr. Cox on Scrubs would call “bastard-coated bastards with bastard filling” so that we find the U. K. ‘s David Bilsborough, in an interview that’s richocheted around the portion of cyberspace devoted to fantasy, congratulating himself thusly: “Yes, my heroes are foul-mouthed, go to the pub, smoke roll-ups, get divorced, do ca-ca in the woods, and, truth be told, after all that time on the road, smell pretty high. They also fight out of desperation and fear rather than bravery or honour, like thugs or butchers, and there’s no glory, only blood and vomit.” Granted, the dramatis personae of these new professional grittyists never require diuretics or laxatives; in the unlikely event that Darrell K. Sweet were to be commissioned to paint a cover for one of their books, after sampling a chapter he’d probably react like Mr. Creosote in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. But other than that, Karl Edward Wagner and Glen Cook did it first and did it grittier decades ago, and the straining to be unholier-than-thou can be rather like an effort to weave Severian’s fuligin cloak (fuligin is “the color that is darker than black” in Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun).

Abercrombie has oh-so-much more than grittiness to offer; his characters are in the gutter, but some still gaze starward even if the fog of war and the fug of disillusionment veil the celestial lights. Events conspire ceaselessly against belief in a better world, but the people that become important to the reader cling to the belief that they can be better versions of themselves. Their best weapon against the enveloping darkness, their only Phial of Galadriel, is usually humor, and of no one is that more true than Inquisitor Glokta, once the Union’s beau sabreur as a champion fencer and dashing cavalryman, now, after prolonged torture as a POW, Arch Lector Sult’s principal dogsbody. His experiences have reduced his once-athletic body to a desecrated tomb, which his mind still haunts: “Eight years since the Gurkish released me, yet I am still their prisoner, and always will be.”

Having been so thoroughly tortured, there was apparently naught for Glokta to do but become a torturer, an Inquisitor, himself. His obvious predecessor in this specialty is the aforementioned Severian, but partway through The Shadow of the Torturer Wolfe’s character leaves his Guild, whereas Glokta plies his trade for 3 whole books. In addition, Severian is a famously unreliable narrator, whereas Glokta is an infamously reliable POV character in that he makes no excuses for anyone, least of all himself. Torture is nothing new in modern fantasy; recall Uccastrog, CAS’ Isle of the Torturers, the Valbroso/Zorathus interlude in The Hour of the Dragon, and Aragorn’s coercive interrogation of Gollum. But never before have we spent so much time looking over the shoulder of an adept like Glokta; it cannot be a coincidence that The First Law appeared during a period in which our world became “The Pit and the Pendulum” writ large. In popular culture torture has been Jack Bauer’s go-to move, his shortcut, the Alexander-blade with which he solves the Gordian knots of attentat after attentat. Torture is the entry, blood-red and boldfaced, on John McCain’s resume that sets him apart, and for a time set him against several powerful exponents of the practice’s efficacy. What is torture and what isn’t? How often does the torturer predetermine the answers to be extracted before he even initiates the questioning? Can torture “truly” ever be of epistemological utility? How does the experience change the torturer as well as the person being tortured?

Questions of that sort ask themselves while Glokta is asking questions, and each session demonstrates the author’s instinct for just how far to go. What is described is not so much disgusting as it is indicative of Glokta’s disgust with himself. Abercrombie has much of Martin’s ruthlessness and some of his ruefulness, and Glokta is his Tyrion Lannister, his outsider-as-insider. Both characters are simultaneously “players” and “sportscasters,” but of a special sort in that they challenge, even subvert the games in which they participate and on which they comment.

Glokta moves, painfully, against an urban backdrop; the other towering character of The First Law, although he passes through Adua, is the product of a North that’s all Abercrombie’s own own but also archetypal. A region as cold and gray as the stones underfoot, part Scottish highlands, part the Scandinavia of the baresark, the blood-eagle, and the Holmgang, and entirely unforgiving of either pacifism or pretense. Here war is the province of “Thralls, peasants pressed into service, lightly armed with spear and bow, fast moving in loose groups,” of Carls, each chieftain’s “own household warriors, well armed and armoured, skilled with axe and sword and spear, well disciplined,” and of “the Known Men, the Named Men, those warriors who’ve earned great respect in battle,” who captain the Carls, or “act as scouts or raiders.” Tom Shippey described chapters 6 to 8 of The Hobbit as “exploring with delight that surly, illiberal independence often the distinguishing mark of Old Norse heroes,” and surly, illiberal independence has seldom been as endearing as it is with Abercrombie’s Northrons. Their sagas trail them like second shadows:

“Northerner, eh?” asked a massive shape in the doorway.

“Aye, who’s asking?”

“The Stone-Splitter.”

He was big this one, very big, and tough, and savage. You could see it on him as he shoved the cupboard away with his huge boot and crunched forward through the broken plates. It meant less than nothing to the Bloody-Nine though — he was made to break such men. Tul Duru Thunderhead had been bigger. Rudd Threetrees had been tougher. Black Dow had been twice as savage. The Bloody-Nine had broken them, and plenty more beside. The bigger, the tougher, the more savage he was, so much the worse would be his breaking.

Even the most inventively choreographed and insistently kinetic action scenes can come across as faceless, pointless scrums unless the participants register as characters. The power of the blows struck is contingent upon how powerfully conceived, how striking, the combatants are. Most of the sword-and-sorcery writers of the Seventies who weren’t named Wagner, Saunders, or Smith either never realized this or never incorporated the realization in their quickie cash-ins. Abercrombie triumphs in this arena; with his aging warrior Logen Ninefingers, “a man who’s wrought more death than the plague, and with less regret,” we’re talking an advent of a similar order of magnitude to when Druss the Deathwalker, more granitic and impregnable than the fortress he was defending, stymied the Nadir back in 1984, or the king of Aquilonia first snarled “Who dies first?” in 1932. I don’t bandy such comparisons lightly, but Logen, a laborer at “dark work, that needs doing,” larger than life and as much of a fell sergeant as death, is deserving.

Although “a man made of murder,” Logen feels too much to be merely a killing machine; he knows he is slipping and slowing. He possesses the “gift” of being able to speak to spirits, and (despite that hyperbolic less-remorse-than-the-plague claim) the curse of being aware of how many ghosts drift dolorously in his wake. When he surveys the unhallowed past that was the prologue to the self presented in The Blade Itself, he starts off sounding like Conan in “Black Colossus,” but ends up closer to William Munny in Unforgiven:

“I’ve fought in three campaigns,” he began. “In seven pitched battles. In countless raids and skirmishes and desperate defenses, and bloody actions of every kind. I’ve fought in the driving snow, the blasting wind, the middle of the night. I’ve been fighting all my life, one enemy or another, one friend or another. I’ve known little else. I’ve seen men killed for a word, for a look, for nothing at all. A woman tried to stab me once for killing her husband, and I threw her down a well. And that’s far from the worst of it. Life used to be cheap as dirt to me. Cheaper.”

“I’ve fought then single combats, and I won them all, but I fought on the wrong side, and for all the wrong reasons. I’ve been ruthless, and brutal, and a coward. I’ve stabbed men in the back. Burned them, drowned them, crushed them with rocks, killed them asleep, unarmed, or running away. . .”

Throughout the 3 novels, we observe Logen Ninefingers (barely) surviving duels and battles in which craft and chance act as warp and woof, but Abercrombie also has a pitch-black ace up his chain-mailed sleeve: In certain extremities, against certain enemies, this barbarian, intimidating enough in his own right, relinquishes control to the Bloody-Nine, and we realize that a man and a purely destructive, trans-berserkerian force are sharing the same skin. Logen doesn’t need a Stormbringer or Druss’ Snaga the Sender, Logen becomes a Stormbringer. Each time the Bloody-Nine fights (and Abercrombie is canny about picking his spots) a terrible beauty is born, a Totentanz of exhilaration and excruciation.

“Dance!” laughed the Bloody-Nine, and the sword reeled around him. He filled the air with blood, and broken weapons, and the parts of men, and these good things wrote secret letters, and described sacred patterns that only he could see and understand. Blades pricked and nicked and dug at him but they were nothing. He repaid each mark upon his burning skin one-hundred fold, and the Bloody-Nine laughed, and the wind, and the fire, and the faces on the shields laughed with him, and could not stop.

He was the storm in the High Places, his voice as terrible as the thunder, his arm as quick, as deadly, as pitiless as the lightning.

Abercrombie recently reminisced to Juliet Marillier at the Writer Unboxed site about creating Logen “seven or eight years” before The Blade Itself was accepted for publication:

[He] was maybe a bit more thoughtful than your average barbarian even in his first incarnation, but he didn’t have that edge of world-weariness, the sense of humour, or nearly such a dark side. I guess, on the specific issue of Logen’s development, in the intervening years between the first effort and the second I had some minor contact with violence which was enough to make me appreciate how totally divorced from reality is the heroic ideal about fighting that is often portrayed in heroic fantasy. Violence has this glamour, this attraction, especially for men, but in reality is utterly destructive both for victim and perpetrator, and even for those on the periphery. So Logen became a way of exploring that gulf between the heroic ideal and the dark realities of being a man of violence.

In one blog-post Abercrombie confessed that he strives to imitate Sergio Leone “in all things,” and there is something of Harmonica and Frank killing their way toward each other in Once Upon a Time in the West in Logen’s relationship with his former taskmaster Bethod, who “forced the North together, with fire, and fear, and steel” :

“I ran before,” he muttered, “and I only ran a circle. For me, Bethod’s at the end of every path.”

He, his fellow wolfshead the Dogman, Glokta, Ardee, and a “Black Sonja”-figure named Ferro Maljinn (“Death was her trade and her pastime” are foremost among the who’s who, but what about the where’s where? “The roads from Shaffa to Ul-Khatif, from Ul-Khatif to Daleppa, from Daleppa to the sea, all are thick with soldiers. The Emperor puts forth all his strength. The whole South moves. Conscripts from Kadir and Dawah, wild riders from Yashtavit, fierce savages from the jungles of Shamir, where men and women fight side by side.” As in The Malazan Book of the Fallen, multiple landmasses are convulsed by invasion and conquest; fortunately, Abercrombie is good at naming place-names:

. . .Names in fantasy are hugely important, and potentially can render a character interesting or ridiculous at a stroke. I agree that it’s particularly irritating when names don’t seem to have any consistency or meaningful root. Tolkien obviously solved that by inventing whole histories and languages to draw from. I took the route of least resistance by — as you observe — basing my various cultures loosely on real-world equivalents so that I had at least some kind of template to draw from. Stealing them, in essence, but partly in the hope that the names might carry in them some echoes of the real world cultures from which they were drawn, give readers a kind of shorthand to identify the kinds of people we were talking about. So the Union I based around a kind of Holy Roman Empire (largely Germanic) with some banking and commerce from medieval Flanders and a political system closer to the Venetian Republic. That produced names like Sult, Marovia, Valint and Balk, Bremer dan Gorst. Gurkhul was more like an Ottoman Empire that had absorbed a whole range of Middle-Eastern and African cultures, producing names like Uthman-ul-Dosht, Khalul, Mamun, and Ferro Maljinn. With the North I went for something slightly different, a kind of Viking or Scots culture, but with a northern English tilt to the language, and in which the men were given names when they reached manhood related to some deed they’d done or the place they’d done it — things like Rudd Threetrees, Caul Shivers, Forley the Weakest, and Black Dow.

Stealing them, in essence, but hoping for “some echoes of the real world cultures” and “a kind of shorthand” — this is of course the Howardian / Hyborian approach to nomenclature, and a reminder of just how myopic and ignorant the contention that REH and his techniques are non-factors in contemporary fantasy really is. Like Howard’s Turan, like Paul Kearney’s Merduks in The Monarchies of God, Gurkhul is on the march, a dread empire that feeds on more than just its own successes:

“This war will not be like the last. Khalul finally sends forth his own soldiers. An army many long years in the making. The gates of the great temple-fortress of Sarkant are opening, high in the barren mountains. I have seen it. Mamun comes forth, thrice-blessed and thrice-cursed, the fruit of the desert, first apprentice of Khalul. Together they broke the Second Law, together they ate the flesh of men. The Hundred Words come behind, eaters all, disciples of the Prophet, bred for battle and fed over these long years, adepts in the disciplines of arms and of High Art.”

Other standout settings include far western wastelands once the seat of an Old Empire, its capital a post-imperial necropolis the catacombs of which are no haven for persecuted believers but the haunt of inhuman inheritors. Bayaz, Abercrombie’s far-sighted, long-lived, short-fused Magus, assembles an inauspicious fellowship for an ominous quest in this region, noting “We are left only with the ruins, and the tombs, and the myths. Little men, kneeling in the long shadows of the past.” A fast clean style does not prevent Abercrombie from being invitingly quotable:

“Some of us are only suited to dark tasks.”

“There’s nothing worth less than what men think of you after you’re back in the mud.”

“A man with a spear needs a lot of friends, and they all need spears as well.”

“The recruiting sergeant sells dreams but delivers nightmares.”

“Maidens might wet themselves over cheap and worthless victories, but they don’t so much as blush for ‘I did my best.'”

“But good men will only go so far along dark paths. Others must walk the rest of the way.”

“Do you know what’s worse than a villain? A villain who thinks he’s a hero.”

“Only the entirely worthless are entirely free. The worthless and the dead.”

“They say you can see all the beauty in the world in the way a hanged man swings.”

“The more you kill, the better you get at it. And the better you get at killing, the less use you are for anything else. Seems to me we’ve lived this long ’cause when it comes to killing we’re the very best there is.”

“You have no understanding of the war you fight in, of the weapons and the casualties, of the victories and the defeats, every day. You do not guess at the sides, or the causes, or the reasons. The battlefields are everywhere.”

It was a bad day for men, all in all, and a good one for the ground. Always the way, after a battle. Only the ground wins.

Steven Erikson enjoys sinking an elbow into the well-padded ribs of comfort-food fantasy, and so apparently does Abercrombie:

“I’ve been trying to get through this damn book again.” Ardee slapped at a heavy volume lying open, face down, on a chair.

“The Fall of the Master Maker,” muttered Glokta. “That rubbish? All magic and valor, no? I couldn’t get through the first one.”

“I sympathise. I’m onto the third and it doesn’t get any easier. Too many damn wizards. I get them mixed up one with another. It’s all battles and endless bloody journeys, here to there and back again. If I so much as glimpse another map I swear I’ll kill myself.”

By the time the reader reaches Last Argument of Kings, Crummock-i-Phail, “the maddest bastard in the whole damn North” and a briar in Bethod’s boot, talks Logen, the Dogman, and a few other Named Men into holing up in “a place well loved by the moon. A strong valley, and watched over by the dead of my family, and the dead of my people, and the dead of the mountains, all the way back until when the world was made.” The ensuing siege of their makeshift fastness in the simply-but-evocatively named High Places surely has David Gemmell building a furniture-fort in the Valhallan meadhall and daring REH & KEW to dislodge him. And because Bethod hurls allies-who-aren’t-men against the walls and gates before risking his Carls, anyone who thrilled to the Uruk-hai massing in front of Helm’s Deep quite simply can’t afford to miss this.

Tom Shippey borrowed the phrase “the infantry of the old war” from Tolkien’s Beowulf essay to describe the orcs, and we’ve grown accustomed to such catapult-fodder with Stephen R. Donaldson’s ur-viles, Guy Gavriel Kay’s urgach, and Robert Jordan’s Trollocs. Abercrombie’s Shanka (“Flatheads” to Logen) imprint themselves on readers a bit more emphatically, in part because the Bloody-Nine’s hatred rages like a wildfire when they’re nearby. They were fashioned from “clay, and metal, and left-over flesh” but driven “into the darkest corners of the world, and there they have grown and bred again, and now come forth to grow, and breed, and destroy, as they were always meant to do.” Aside from the Shanka, Abercrombie is “Gemmellian” in that most of his monsters are human, or formerly human, like Balaz, who could almost be the author’s attempt at an unsettling rewrite of the scene in The Two Towers where Gimli says “I thought Fangorn was dangerous” and Gandalf pounces on the word:

‘Dangerous!’ cried Gandalf. ‘And so am I, very dangerous: more dangerous than anything you will ever meet, unless you are brought alive before the seat of the Dark Lord.’

In terms of future featured creatures, while it doesn’t sound like any mass breakout from a fantasticated bestiary will occur in Best Served Cold, a standalone scheduled for June of 2009, the next Abercrombie does promise to be a joy to read:

A very dangerous woman is betrayed by her employer, her brother killed and she left maimed. So she sets out to seek vengeance on him and the six men who helped, and recruits a set of mismatched and untrustworthy allies — a master poisoner and his unlikely apprentice, a psychopathic convict obsessed with numbers, a Northman trying to escape a life of violence and failing (not who you’re thinking), a torturer (not who you’re thinking), and an over-the-hill mercenary who’d do anything for one last drink. Soon the most deadly killer in the world is dispatched to put an end to their schemes for good, while in the background, and then the foreground, a bitter war rages for control of Styria. The results, as one would expect, are fast and furious, occasionally humorous, always unpredictable, and very, very bloody.

The Northman-who-isn’t-Ninefingers and the torturer-who-isn’t-Glokta bespeak a writer disinclined to duck challenges.

Revisiting the issue of length, The First Law might appear overlong to some readers, especially those with a pulp-trained attention span, but as a prodigy of heroic fantasy storytelling the 3 books are not nearly long enough. Saying goodbye to Inquisitor Glokta and Logen Ninefingers aches like a bereavement. A preference need not be a prison, and while we all hope that, Valka willing, new markets for sword-and-sorcery novelettes and novellas emerge someday, long-form doesn’t mean malformed. With Joe Abercrombie our favorite subgenre is in good, and formidably sword-calloused, hands.