The Sword-and-Sorcery Legacy of Clark Ashton Smith

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

Clark Ashton Smith gets credit for a lot of things, at least by those who are aware of his work. He was arguably the first poet to versify from a truly cosmic viewpoint when he wrote his legendary “The Hashish-Eater.” His poetry and prose, as well as his inimitable drawings, paintings and sculptures, captured the attention and respect of H.P. Lovecraft, who name-checked CAS in his own tales more than any writer, even Dunsany. Smith was a highly valued correspondent of Robert E. Howard. Clark Ashton Smith was admired by (and sometimes mentored) younger authors such as Bradbury, C.L. Moore and Leiber. His tales of Zothique were patent inspirations for later works by Jack Vance and Gene Wolfe.

One thing that Clark Ashton Smith decidedly does not receive much credit for is being one of the founding fathers of the heroic fantasy genre. On this, his one hundred and seventeenth birthday, I’d like to give him his due.

It would be hard to find anyone to dispute the fact that Robert E. Howard created the Sword-and-Sorcery genre when he hammered out “The Shadow Kingdom” on his Underwood. Written in late 1926 and published in 1929 by Weird Tales, “The Shadow Kingdom” was soon followed by more S&S yarns like “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune” and “Red Shadows.” Those proved popular and and soon more supernatural adventures featuring the likes of Bran Mak Morn and Turlogh Dubh hit the pages of The Unique Magazine. Seemingly, REH stood alone during the late ’20s and early ’30s as the lone fictioneer willing and able to craft tales of heroic fantasy. Or did he?

In 1931, a little over two years after the publication of “The Shadow Kingdom” (and a solid year before the first Conan yarn), Weird Tales published “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros” by Clark Ashton Smith. It told the story of Satampra Zeiros and Tirouv Ompallios, two thieves from the lost continent of Hyperborea. Just good ol’ boys making their way any way they knew how, but that was a little bit more than the law would allow.* Finding themselves short of pazoors, the twain, after consultation over a wine-skin, decide to seek the shunned ruins of Commoriom. Once there, they try to plunder the basalt temple of Tsathoggua, but find that the fane still has a guardian…

I would like someone to tell me exactly what would disqualify the story described above from being classed as “Sword-and-Sorcery”? Satampra is a big, lusty, wine-loving scoundrel with no shortage of guts. Essentially, he falls into the same category as later characters from REH such as Kalmbach and Taurus of Nemedia. In fact, who’s to say that Howard wasn’t partially inspired by CAS’ tale when he crafted “The Tower of the Elephant”? Also, keep in mind that even Howard had yet to spin a yarn like “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros” in 1931. Not Kull nor Solomon Kane nor Turlogh Dubh were known for robbing shadow-haunted temples for treasure (though it is probable that Kull did so in some untold tale).

The next story from CAS to fall pretty squarely in the purview of heroic fantasy was “The Ice-Demon,” published by Weird Tales in early ’33. In this tale, once again set in Hyperborea, we find two venal merchants being led to the cursed (and glaciated) treasure of King Haalor by one Quanga. Quanga is described as a “huntsman,” a man skilled in woodcraft, fearless and lacking in superstition, but with a taste for gold. The three treasure-hunters discover that finding the hoard was the easy part…

Once again, I fail to see why this tale should be excluded from the canon of early Sword-and-Sorcery. If so, then we may be parsing hairs to the point of absurdity. If, as is often asserted, Sword-and-Sorcery is to fantasy what noir is to detective fiction, then “The Ice-Demon” qualifies as Sword-and-Sorcery.

“The Charnel God,” praised as “magnificent” and “tremendously powerful” by REH, was published in early 1934. Phariom and his young bride find themselves in the city of Zul-Bha-Sair after surviving the massacre of their caravan. His wife falls into a death-like coma and the priests of the ghoul-god Mordiggian come for her. Phariom attacks but is beaten senseless by the superior numbers and supernal strength of the priests. Going after his woman, Phariom falls in with a necromancer who also seeks something from the temple of Mordiggian…

Despite Howard’s endorsement, I feel that this story tends slightly more to the fringe of heroic fantasy than the previous two. This is due to Phariom’s somewhat reluctant and peripheral role in the tale. That said, the story fully deserves its reputation as one of CAS’ classics. A truly rippin’ yarn, as John C. Hocking once noted. I’ve long wondered if the subterranean temple of Mordiggian (and his strange minions) provided some small inspiration for REH when he wrote “The Servants of Bît-Yakin.”

My fellow blogger [redacted] has already noted that “The Colossus of Ylourgne,” which was published in the spring of ’34, is a Sword-and-Sorcery yarn. The protagonist, Gaspard du Nord, is a lapsed pupil of the necromancer, Nathaire. While possessing some skill in the black arts, Gaspard is no frail bookworm and he’s got physical courage in spades. After catching a dark glimmer of what his former tutor intends, he sets out to beard the necromancer in his lair. Gaspard’s final stroke against what Nathaire has become is a ballsy move worthy of even a Howardian hero. If any seek to exclude this tale from the S&S canon due to Gaspard’s use of magic, I suggest they back up that position by throwing all their Elric volumes on the bonfire as well.

When “The Black Abbot of Puthuum” appeared in the pages of WT in late 1936, Smith and Howard no longer stood alone in the dawn of heroic fantasy’s First Age, since C.L. Moore had seen four of her “Jirel of Joiry” tales published in The Unique Magazine starting in late 1934.

“The Black Abbot of Puthuum” finds Cushara and Zobal, veteran guards of King Hoaraph, acquiring a beautiful virgin for His Majesty’s harem. Accompanied by the watchful eunuch, Simban, the four start back across the desert of Izdrel. They are soon surrounded by a moving wall of sorcerous darkness which only dissipates at the front gate of a lonely and dilapidated monastery. There they encounter an abbot of immense size and disturbing mien…

I’m sorry. This tale is Sword-and-Sorcery. If I didn’t know that Fritz Leiber had already finished “Adept’s Gambit” in early 1936, then I would swear that this was an influence on his (and Harry Fischer’s) Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tales.

Clark Ashton Smith decided to give Satampra Zeiros and Sword-and-Sorcery one final go in 1957. “The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles” follows Satampra as he and his sweetheart-in-crime, Vixeela, attempt to thieve the begemmed chastity-belts worn by the “virgins” of Leniqua the moon-god. Sword-and-Sorcery ensues.

Clark Ashton Smith did not write Howardian Sword-and-Sorcery. That goes without saying. As he nearly always did, CAS trod his own literary path and wrote Klarkash-Tonian heroic fantasy. The lineage of that much-ignored strand in the tapestry of our favorite genre can be traced from C.L. Moore and Leiber on through Jack Vance, Moorcock and beyond. I’d like to think I have made a strong case for Smith’s inclusion within the mighty halls of heroic fantasy. More than that, I hope that at least some of you will go now and read those tales he created with such care and art and passion.

*Please forgive my small homage to Waylon Jennings. I couldn’t resist.

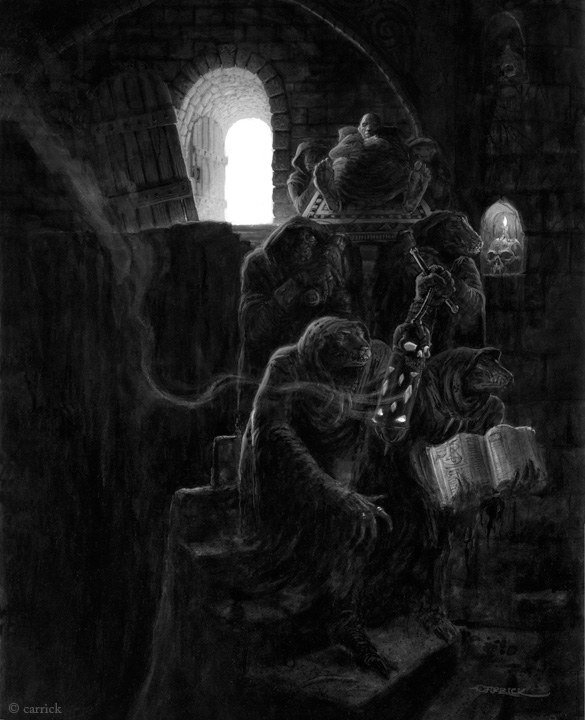

**Art by Justin Sweet, Paul Carrick and Erol Otus.