Saluting the Sorcerer

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

posted by Leo Grin

Print This Post

Print This Post

EDITOR’S NOTE: First published in 1963, “The Sorcerer Departs” was Donald Sidney-Fryer’s magisterial bio-critical essay on the work of poet and fictioneer Clark Ashton Smith. Almost a half-century on, it remains the best. The full 17,000-word version, accompanied by new editorial matter, is currently available in a handsome booklet from Silver Key Press.

On the occasion of the Bard of Auburn’s 117th birthday, and with the permission of Sidney-Fryer himself, The Cimmerian hereby presents a vastly truncated version of that essay to its readers, which we have titled “Saluting the Sorcerer.” It is our hope that the piece stimulates you to seek out Smith’s work — most of which is widely available in various in-print and out-of-print editions — as well as begin to delve into the prodigious poetry and critical writings of Donald Sidney-Fryer.

SALUTING THE SORCERER

By Donald Sidney-Fryer

I pass. . . but in this lone and crumbling tower,

Builded against the burrowing seas of chaos,

My volumes and my philtres shall abide:

Poisons more dear than any mithridate,

And spells far sweeter than the speech of love….

Half-shapen dooms shall slumber in my vaults

And in my volume cryptic runes that shall

Outblast the pestilence, outgnaw the worm

When loosed by alien wizards in strange years

Under the blackened moon and paling sun.

In an age dominated by those whom George Sterling once derided as “the brave hunters of fly-specks on Art’s cathedral windows,” the poet Clark Ashton Smith (1893–1961) is sui generis. His Art embodies the thesis put forth by Arthur Machen in his study Hieroglyphics (1902) that “great writing is the result of an ecstatic experience akin to divine revelation.” The first major poet in English to be influenced by Poe, Smith certainly does not belong to any Weird Tales “school” — nor yet does he belong to any Gothic or neo-Gothic tradition except that of his own synthesis and creation. In the words of his own epigram: “The true poet is not created by an epoch; he creates his own epoch.”

Smith was born of Yankee and English parentage on January 13th, 1893, in Long Valley, California, about six miles south of Auburn. In 1902 his parents, Fanny and Timeus Smith, moved to Boulder Ridge, where father and nine-year-old son built a cabin and dug a well. Here Smith lived almost continuously until 1954, and one can easily imagine the effect that the surrounding countryside had on the sensitive and imaginative boy. It was a veritable garden of fruit trees, evergreens and park-like areas located on the rolling foothills of the Sierras, while arching overhead the nocturnal immensitudes of the heavens were rendered remarkably clear in the clean, smog-free country air.

Writing later that “As a schoolboy, I believe that I was distinguished more for devilment than scholarship,” Smith did not go on to either high school or college. He preferred to conduct his own education. (Later, when he turned down a Guggenheim scholarship, it was for the same reason.) To judge by his creative work, we may be sure that Smith — always an omnivorous but discerning reader — proved to be his own best teacher.

From the very first Smith seems to have been attracted to the exotic and faraway. He had terrific nightmares from his early boyhood onward — many of his mature horror stories were based on these nightmares. He once wrote that his “first literary efforts at the age of eleven, took the form of fairy tales and imitations of The Arabian Nights. Later, I wrote long adventure novels dealing with Oriental life, and much mediocre verse.”

In 1906, Smith made an important literary discovery:

Unique, and never to be forgotten, was the thrill with which, at the age of thirteen, I discovered for myself the poems of Poe in a grammar-school library; and, despite the objurgations of the librarian, who considered Poe “unwholesome,” carried the priceless volume home to revel for enchanted days in its undreamt-of melodies. Here, indeed, was “balm in Gilead,” here was a “kind nepenthe.”

Later, and equally important, Smith discovered Poe’s short stories. Then when almost fifteen another epochal influence appeared:

Likewise memorable, and touched with more than the glamour of childhood dreams, was my first reading, two years later, of “A Wine of Wizardry,” [by George Sterling] in the pages of the old Cosmopolitan. The poem, with its necromantic music, and splendours as of sunset on jewels and cathedral windows, was veritably all that its title implied. . . .

The cosmic-astronomic poetry of Sterling, together with the beauty of the Auburn countryside, may have suggested to Smith to try his hand at the same theme. Through the suggestion of Emily J. Hamilton, a teacher at the Auburn high school, Smith came into personal contact with Sterling, at that time the unofficial poet laureate of the West Coast and very much the social lion. This personal friendship and correspondence lasted for sixteen years, until Sterling’s death in November 1926.

During 1911–1912 the eighteen-year-old wrote his first mature poetry, soon published with Sterling’s aid as The Star-Treader and Other Poems. The leading San Francisco newspapers proclaimed Smith “the Keats of the Pacific Coast,” and discerning critics hailed him as a prodigy and a genius. Sterling later wrote that “the story of… [Smith’s] triumph with his neighbors, when hundreds of copies of his first book of verses were promptly bought up in a small California hill town is a romance in itself.” Thus Smith made his debut into the bohemian literary and artistic life on the West Coast, centered in San Francisco and the surrounding area, that at various times included such notables as Bret Harte, Frank Norris, Jack London, Ambrose Bierce, Joaquin Miller, Edwin Markham, Ella Sterling Mighels, Charles Warren Stoddard, Nora May French, Ina Coolbirth, Gertrude Atherton, and many others. However, for all the éclat of his introduction to this life, Smith continued to live with his parents at their cabin on Boulder Ridge.

During 1911–1912 the eighteen-year-old wrote his first mature poetry, soon published with Sterling’s aid as The Star-Treader and Other Poems. The leading San Francisco newspapers proclaimed Smith “the Keats of the Pacific Coast,” and discerning critics hailed him as a prodigy and a genius. Sterling later wrote that “the story of… [Smith’s] triumph with his neighbors, when hundreds of copies of his first book of verses were promptly bought up in a small California hill town is a romance in itself.” Thus Smith made his debut into the bohemian literary and artistic life on the West Coast, centered in San Francisco and the surrounding area, that at various times included such notables as Bret Harte, Frank Norris, Jack London, Ambrose Bierce, Joaquin Miller, Edwin Markham, Ella Sterling Mighels, Charles Warren Stoddard, Nora May French, Ina Coolbirth, Gertrude Atherton, and many others. However, for all the éclat of his introduction to this life, Smith continued to live with his parents at their cabin on Boulder Ridge.

Between 1912 and 1922, the year Smith’s second major poetry collection appeared, Smith first came to know both Les Fleurs du Mal and the Petits poèms en prose of Baudelaire, and began contributing to a wide variety of magazines. Sometime after the publication of The Star-Treader, Smith suffered a nervous breakdown and an attack of tuberculosis; from the former he fortunately recovered but the latter, while arrested, continued to bother him intermittently the rest of his life.

In 1918 the Book Club of California issued fifteen of Smith’s poems in an édition de luxe of 300 copies, under the title of Odes and Sonnets — the preface by George Sterling contained not only a discerning appreciation of Smith’s genius but also an incidental prophecy that Smith was “unlikely to be afflicted with present-day popularity.” Distinguished recognition, however, was immediate. Edwin Markham, a poet now most famous for the poem “The Man With The Hoe,” wrote: “These poems have lines of unusual beauty, glints and gleams of true genius. There is something terrific in Smith, as there was in John Martin, the illustrator of Milton’s Paradise Lost. It cheers me to know that you Californians have honoured yourselves in your honouring of this distinguished poet.” Grace Atherton Dennon, editor of the west-coast poetry magazine The Lyric West, wrote: “Your poems are rich in feeling and expression. I regard you as a genuine poet, one whose name will endure.” And from across the Atlantic the distinguished English poet and essayist Alice Meynell Smith wrote: “I think the imagination in your poems very remarkable, and wonderfully original. They are poems of true genius.” In recognition of his services to literature the Book Club of California presented Smith with a bronze plaque designed by the noted San Francisco sculptor Edgar Walter, an honor bestowed only on such literary notables as Sterling and Edwin Markham.

About this time Smith began a number of important correspondences, one with the poet Samuel Loveman, a close friend of Ambrose Bierce and the author of The Hermaphrodite and Other Poems; and, about 1922–1923, possibly through the offices of Loveman, with H. P. Lovecraft. This last was the beginning of what must have been a wonderfully rewarding friendship through letters for both men, as it is evident that they held many views, opinions, and tastes in common — in archaeology, astronomy, astrology, languages ancient and modem (and a consequent interest in the systematic invention of personal and place names for fictional purposes), demonology, sorcery, mythology, legendry, folklore. Yet for all such similarities in taste and opinion, the creative work of each man is strikingly different from that of the other, and each fully appreciated the other’s genius.

In 1922, Smith selected and arranged into book form the best from the work of the years following the appearance of his first volume, and that December published in Auburn his second major poetry collection Ebony and Crystal, Poems in Verse and Prose, with a preface by George Sterling and dedicated to Samuel Loveman. Again distinguished recognition was immediate. Henry Anderson Lafler wrote: “I wonder that you speak so slightingly of these poems. It seems to me that nothing being written today overtops them. You and George Sterling are two eagles in ‘strong level flight,’ winging sunward above flocks of sparrows.”

The novelist and poet Frank L. Pollock wrote:

I must make you all possible compliments on your magnificent piece of blank verse, “The Hashish-Eater.” The technique is superb, the verse hard-spun and close-woven. It would be difficult to conceive of greater power and variety of imagination, or a greater splendour of vocabulary. Almost every episode has the material for a long poem in itself — in fact you have used up enough poetical material to make half a dozen volumes of modem poets. As a decorative poem, it seems to me that this is one of the finest things I have ever read. I do not think there are six men living who could have done it — certainly no one else in America. Continually one comes cross absolutely right and infallible lines, giving the joy of a thing perfectly said; or some burst of metaphor that is like a flash of lightning; or some violent and vivid feat of imagination. I could pick examples by scores; there is only an embarras des richesses.

The secretary of the Book Club of California, Alfred M. Bender, was similarly impressed: “Thank you for your wonderful poem, ‘The Hashish-Eater.’ The subject may seem unappealing to many, but it has such richness of imagination, sustained thought, and stately beauty of expression that I am sure it will enhance your reputation and bring you new laurels. It should be an inward satisfaction to add another star to the firmament of California literature. Your place is growing firmer with each new effort.” Smith’s great friend and mentor George Sterling added that “‘The Hashish-Eater’ is indeed a most amazing production. It contains more imagination than anything else I have ever read.” And in the poetry journal L’Alouette for January 1924, appeared a highly favorable review of Ebony and Crystal by Smith’s correspondent living across the continent, H. P. Lovecraft, who gave unstinted and eloquent praise to the volume, especially to its crowning achievement “The Hashish-Eater.”

Unfortunately, the fact that Ebony and Crystal was privately published in a limited edition (as was the following volume, Sandalwood), prevented it from reaching a nationwide audience, with the consequent larger critical recognition. Acclaim of his own age or not, Smith continued on his own supremely independent way, letting no external clamors or censures interfere with the voice of his own personal daemon. During the 1920s he was contributing to a wide range of publications, from those of national or international circulation to the “little” magazines. The poetry journal The Step-Ladder honored Smith by devoting its entire issue of May 1927 to his poems (principally from Ebony and Crystal and Sandalwood). Among this wide range of magazines was one whose founding in 1923 was to play a pivotal role when Smith later came to write short stories. This was Weird Tales “The Unique Magazine” (as the subtitle ran), in which Smith first appeared in the issue for January 1924 with the poems “The Red Moon” and “The Garden of Evil” (later collected into Sandalwood as “Moon-Dawn” and “Duality,” respectively).

During the first half of the 1920s, Smith became a “journalist” and contributed to The Auburn Journal eighty-one poems (fifty-nine originals and twenty-two translations from Baudelaire) and 329 original, and seventeen selected, epigrams and pensées. In October 1925, again in Auburn, Smith published his third major poetry collection Sandalwood, dedicated to George Sterling; a volume distinguished not only for its many beautiful love poems but also for nineteen translations from the French of Charles Pierre Baudelaire, a remarkable accomplishment in view of the fact that Smith knew virtually nothing of the French language a year prior, and hence had learned it in something less than a year. This volume, because of its private printing in a limited edition, has shared the fate of Ebony and Crystal of being little better than unknown. In addition to the recognition given Smith’s poetry of 1911–1925 by divers distinguished literary persons, the newspapers of the San Francisco area accorded long, elaborate, and overall excellent reviews to at least the first two of Smith’s three major early poetry collections. As the result of Ebony and Crystal, one critic wrote apropos of Smith that “Among the living [poets] he stands alone.”

The year 1925 also saw a new development in Smith’s creative evolution: in this same year he had written two short stories. He submitted them to Farnsworth Wright, the editor of Weird Tales, who rejected both, which he very well may have considered a little bit of too much, since both tales are essentially extended poems in prose. The stories proved Smith a unique poet in prose, in the manner of Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death.” In fact, it is not too much to say that technically Smith had almost created — or at least re-created — the genre of the extended poem in prose.

In November 1926, at the Bohemian Club in San Francisco, occurred the death of George Sterling, Smith’s great friend and mentor, ostensibly by suicide, a theory with which Smith never agreed. His death was a source of great bereavement, and Smith remained devoted the rest of his life to Sterling’s memory and to his poetry. A few weeks before, Sterling had said to David Warren Ryder: “Clark Ashton Smith is undoubtedly our finest living poet. He is in the great tradition of Shakespeare, Keats and Shelley; and yet, to our everlasting shame, he is entirely neglected and almost completely unknown.” (Also shortly before his death, Sterling had advised Smith, apropos of the latter’s poems in prose of death and similar subject-matter, to give up “this macabre prose,” a piece of advice Smith fortunately ignored.) One of the very last services which Sterling performed for Smith and the cause of his poetry occurred when the elder poet brought an article for publication into the editorial offices of The Overland Monthly in San Francisco. This article was a highly enthusiastic, almost ecstatic essay on Smith’s poetry entitled “The Emperor of Dreams” and written by the then eighteen-year-old Donald A. Wandrei. The Monthly subsequently published the essay in its issue for December 1926.

After Sandalwood, Smith gave up the creation in quantity of poetry and turned his attention once more to the writing of fiction. Earlier, in 1924, in the August issue of 10 Story Book — a magazine which featured a piquant combination of short stories with what are now known as “girly pictures” — had appeared Smith’s first professional short story since his contributions to The Overland Monthly and The Black Cat in 1910-1912. August 1928 saw Smith’s first appearance in prose in Weird Tales; this was in the form of prose translations of three poems originally in verse by Baudelaire — ”L’Irréparable,” “Les Sept Vieillards,” and “Une Charogne” — presented to the readers as Three Poems in Prose, by Charles Pierre Baudelaire and Translated by Clark Ashton Smith from the French. Smith had translated the verse originals into a supple and idiomatic English prose. In the succeeding issue for September 1928 appeared Smith’s first short story in Weird Tales; however, Smith did not begin the writing of fiction in any quantity until the beginning of the Depression in 1929. We must postulate the years 1925 to 1929/1930 as the period in which Smith was carefully preparing in his imagination the divers backgrounds for his stories.

Between 1929 and August 1936 Smith wrote more than one hundred short stories and novelettes for either Weird Tales under Farnsworth Wright or Wonder Stories under Hugo Gernsback. To the latter Smith contributed a highly imaginative type of science-fiction story. To the former he contributed all manner of tales, many of them laid in Smith’s carefully constructed backgrounds: the primeval continent Hyperborea; “the last isle of foundering Atlantis,” Poseidonis; medieval Averoigne; the last continent Zothique; the planet Xiccarph; and many other worlds. Although these stories may have been known only to a specialized audience, they introduced a new dimension in the art of the short story: many are actually extended poems in prose in which Smith has united the singleness of purpose and mood of the modem short story (as first established by one of Smith’s literary idols, Edgar Allan Poe) together with the flexibility of the conte or tale; an entire short story being unified and, in part, given its powerful centralization of effect, mood, atmosphere, etc., by a more or less related system or systems of poetic imagery. This ranks as a technical achievement of the first order, although it has received relatively little or no recognition. It is indeed fortunate that both Weird Tales and Wonder Stories existed during this period of intense creation in Smith’s life: by providing a more or less ready market for Smith’s stories, they served as the necessary commercial incentive which Smith, genius or not, financially needed.

All during this time (1929–1937) Smith continued to write verse but necessarily in a much smaller quantity. In 1933, George Work, the author of White Man’s Harvest, and one of the then best-known writers in the country, declared Smith “the greatest American poet of today” whose “poems do not compare unfavorably with those of Byron, Shelley, Keats or Swinburne.” In Controversy for November 1934 appeared the article “The Price of Poetry,” by David Warren Ryder. In this article Ryder acclaimed Smith as “a great poet” and as being “in our generation. . . the fittest to wear the mantle of Shakespeare and Keats,” thus adding his considered opinion to the similar one of George Sterling, George Work, and the well-known and respected educator and man-of-letters, Dr. David Starr Jordan, one-time president of the University of Indiana and the first president and “the builder” of Stanford University.

In 1936 the output of Smith’s tales started to drop off, and by the latter ’30s Smith had virtually stopped writing fiction. However, he continued writing verse until his death in 1961. The reasons for this cessation of fiction are not clear: it could have been that he had exhausted even his seemingly inexhaustible fancy; or perhaps the daemon no longer told him “tales of inconceivable fear and unimaginable love”; or Smith may have found the production of his small sculptures (a hobby begun in the early 1930s) more interesting. Numerous deaths also affected him during this time — his mother, Fanny Smith, died in 1935; friend and fellow author Robert E. Howard committed suicide in 1936; his father, Timeus Smith, died in 1937; and in March of this same year H. P. Lovecraft succumbed to cancer. HPL especially proved an enthusiastic and perceptive audience for Smith: both had regularly exchanged manuscripts before their publication and mutually commented on them.

During the late 1930s Universal Studios considered the possibility of filming two of Smith’s most extraordinary tales, “The Dark Eidolon” and “The Colossus of Ylourgne.” This project never materialized, and this may have been a blessing rather than a misfortune, however much Smith could have used the money. To have adapted either of these tales would have required not the typically conventional treatment of Universal Studios but such combined talents as those of Vincent, Alexander, and Zoltan Korda as demonstrated in their classic fantasy film The Thief of Bagdad with its excellent score by Miklós Rózsa. Conrad Veidt, the evil Vizir and archimage in this film, would have been superb as the archimage Namirrha in “The Dark Eidolon” or as the medieval sorcerer Nathaire in “The Colossus of Ylourgne.” Alas, the might-have-been….

Whatever may have been the reasons for the cessation of his writing fiction, Smith only wrote little more than a dozen stories between the late 1930s and his death in 1961. Also, he had returned to his first love, the creation of poetry in verse: by late 1941 Smith had three collections or cycles of verse in preparation: Incantations, The Jasmine-Girdle, and Wizard’s Love and Other Poems (later retitled The Hill of Dionysus). Thus, it was during the penultimate decade of his life that Smith composed and/or assembled his final poem-cycles. Incantations contains mainly poems composed during the 1920s and 1930s, hitherto largely uncollected, as well as many unpublished poems. The Hill of Dionysus and especially The Jasmine-Girdle both contain many poems never-before published; both are cycles of love poems.

Whatever may have been the reasons for the cessation of his writing fiction, Smith only wrote little more than a dozen stories between the late 1930s and his death in 1961. Also, he had returned to his first love, the creation of poetry in verse: by late 1941 Smith had three collections or cycles of verse in preparation: Incantations, The Jasmine-Girdle, and Wizard’s Love and Other Poems (later retitled The Hill of Dionysus). Thus, it was during the penultimate decade of his life that Smith composed and/or assembled his final poem-cycles. Incantations contains mainly poems composed during the 1920s and 1930s, hitherto largely uncollected, as well as many unpublished poems. The Hill of Dionysus and especially The Jasmine-Girdle both contain many poems never-before published; both are cycles of love poems.

And if all the preceding mass of poetry, much of it new, were not already quite enough for a man in his fifties — a man who had moreover in the early part of his career created three major collections of poetry — Smith also experimented with such miniature forms as the quintrain and the haiku, the last surely the quintessence of quintessential forms. All-told, he now created over one hundred miniature poems, a small sampling of which is presented in Spells and Philtres (Arkham House, 1958). In addition, Smith learned Spanish during this decade, made translations from Spanish poets, and even wrote a small number of poems in Spanish. Such productivity, much of it in new forms and in new directions and some of it even in a new language for Smith, must be considered remarkable indeed for a man in age already past the half-century mark. Phoenix-like, the poet had been reborn out of the ashes of the fiction-writer.

The foundation of Arkham House in 1939 by August Derleth assured the publication of four collections of Smith’s short stories in book form: Out of Space and Time (1942), Lost Worlds (1944), Genius Loci and Other Tales (1948), and The Abominations of Yondo (1960). Upon publication of Out of Space and Time, the well-known writer and man-of-letters Benjamin De Casseres in his syndicated column “The March of Events” dated Sep. 23, 1942 (this column appeared on the editorial page of the Hearst newspapers), commented briefly on Smith’s first major prose collection and hailed Smith not only as a great poet and a great storyteller but as “a great prose writer” as well. A large sampling of Smith’s poetry was presented in Smith’s first published Arkham House poetry collection The Dark Chateau (1951), which Smith dedicated significantly “To the Memory of Edgar Allan Poe” and which contains many remarkable poems. A further and still larger sampling may be had in Smith’s second published Arkham House poetry collection Spells And Philtres (1958).

A near lifetime of celibacy, brightened here and there by the bowers of divers “enchantresses” (as he was wont to call them), came to an end in 1954 when Smith married Carol Jones Dorman, the last and “The Best Beloved” of Klarkash-Ton’s enchantresses. Between 1954 and his death in 1961 he maintained his residence alternately in Pacific Grove and near Auburn. The old cabin of the Smiths, in which Clark had lived for over half a century, from 1902 to 1954, burned down to the ground in August 1957. This was understandably a source of deep distress. Smith still chopped wood and did gardening during the last decade of his life, in addition to working on his quintessential sculptures. (During the ’20s, the ’30s, and the ’40s, Smith had done much hard manual labor — fruit-picker, fruit-packer, cement-mixer, hardrock miner, mucker windlasser, wood-chopper, gardener — but his literary output shows very little reflection of this work.) However, these last years saw relatively little literary activity, although he did continue to write poetry sparingly.

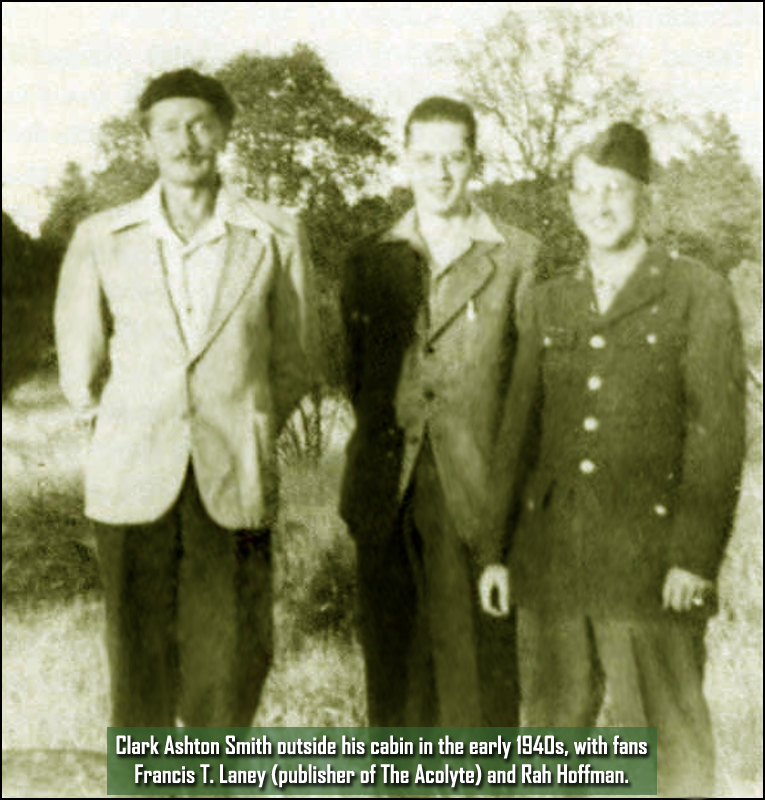

It was toward the latter part of Smith’s last years that the present writer — on two different occasions — had the pleasure of meeting him and his wife Carol at their home in Pacific Grove: in August of 1958 and in September of 1959. I recall with warmth and gratitude the unstinted way in which the Smiths gave of their hospitality and made me feel perfectly at home. I somewhat naively anticipated the poet to speak in a voice as sententious and orotund as that of a sorcerer in one of his tales, but to my considerable surprise Smith spoke in a deep, quiet, pleasant voice that put me instantly at ease. With his trim mustache and his handsome, distinguished features, he seemed a perfect gentleman, affable but not unctuously so, civilized and tolerant, about whom there hovered a certain aura of individuality that would have set him apart anywhere but not in any blatant, affected manner: that true individuality which comes from within and has nothing of the theatrical in it.

Of that first visit I recall in particular a delightful picnic we held on the beach about a block and a half east of their home. It was literally a “golden afternoon” with but a few fleecy clouds high overhead, with the gulls crying about us and the waves lisping among the rocks. Smith wore his beret and Mrs. Smith an immense straw hat which gave her the piquant appearance of a twentieth-century enchantress. With Mrs. Smith generously purveying the food from a straw hamper, we ate a simple but tasty repast of good, crumbly wheaten bread piled with miniature slabs of a sharp cheddar cheese, all washed down with one of the good red wines of California poured into paper cups: a wine of pomegranates from Hyperborea held in goblets of crystal and orichalch could not have tasted any better. Our conversation was informal and covered a wide range of topics, occasionally spiced by some wise, witty, and often ironic comment from Smith on the contemporary political and international scene.

My second visit featured, among other things, a lengthy discussion apropos divers literary figures, especially Poe and Baudelaire. The discussion reached its climax when Smith, with an unforgettable intensity, read aloud in French one of the powerful sonnets of Baudelaire. Smith commented afterwards, “That’s terrific stuff!” I nodded my head in agreement and said, “Well, it certainly wasn’t written by Alfred Lord Tennyson!” Then we both laughed, breaking the tension. Earlier, upon my noticing and commenting upon a “complete works” of Poe in some eight or ten volumes on a bookshelf in the dining room, Smith confided that he had read virtually everything written by Poe that he had been able to obtain.

However, it was during my first visit that Smith showed me his portfolio of drawings and paintings. I must confess myself somewhat taken aback by their deliberately primitive technique, having become somewhat spoiled by the technical excellence of Smith’s verse and prose; but there were a number of demonic heads which struck me as powerful and original. Smith’s sculptures, on the other hand, as deliberately primitive as the paintings, impressed me far more favorably and suggested something Egyptian or Mayan or Peruvian of the Inca period, without being quite the same as those. These carvings of Smith’s possess a quality rare in sculpture, which generally surrenders its essence at once to the beholder, especially sculpture of a conventionally technical perfection. Smith’s carvings grow gradually in the onlooker’s appreciation: the more one sees them, the more fascinating they become, adumbrating an essence never fully revealed but extending itself infinitely.

Smith was as generous and fine a friend as Sterling must have been. I happened to lack only one of Smith’s volumes of poetry, the slender reprint collection Nero and Other Poems, published by The Futile Press. Smith took a copy he had given and inscribed to his wife, cut out the inscription page, wrote in a new inscription to me and them gave me the book gratis. I protested — somewhat feebly, I admit — but Clark and Carol insisted I keep it. Thanks to their dual generosity, today I have in my personal library this copy of Nero and Other Poems or, in the words of Smith’s inscription, “this relic from an ironically named printing press.”

The Bard of Auburn remained the poet to the very end. He composed his last poem “in the midst of the Sabbath pandemonium of dogs, brats and autoes” of June 4th, 1961. A little more than two months later, at the age of sixty-eight, Clark Ashton Smith died quietly in his sleep at his home in Pacific Grove. Neither the science-fiction nor fantasy magazines even mentioned Smith’s death. He died as he had lived for the most part, as an outsider.

Overall, Smith was by no means a prolific writer, except in the sense of creating many writings of a high literary merit. There are about 140 tales extant, about forty poems in prose, and probably about six-hundred poems in verse. For a person who dedicated most of his life to poetry, Smith wrote comparatively little. He maintained only about ten or fifteen correspondences of any importance or length. Smith, with his relatively small output of work, provides a striking contrast to those authors whose complete collected works fill one, two, or three full library shelves, or sometimes even more. But if the quantity of his overall output is negligible, the quality is the reverse.

Overall, Smith was by no means a prolific writer, except in the sense of creating many writings of a high literary merit. There are about 140 tales extant, about forty poems in prose, and probably about six-hundred poems in verse. For a person who dedicated most of his life to poetry, Smith wrote comparatively little. He maintained only about ten or fifteen correspondences of any importance or length. Smith, with his relatively small output of work, provides a striking contrast to those authors whose complete collected works fill one, two, or three full library shelves, or sometimes even more. But if the quantity of his overall output is negligible, the quality is the reverse.

His poems and tales form an integral complement to each other. If Smith had written nothing else but his first volume of poems, The Star-Treader, he would still take rank as a unique poet. Marked by an astonishing technical command and assurance, and by an immense vocabulary used with unerring and creative precision, it is as remarkable an achievement today as it was almost a century ago when it was published in 1912. Ebony And Crystal, published in 1922, features all the themes and background in The Star-Treader — cosmic-astronomic, mythological, necromantic — but not only have the poet’s technical and metrical skills attained their perfection, but a new and undeniably universal theme manifests itself — that of love. An important technical innovation is Smith’s revival of that unjustly neglected and deprecated metre in English, the alexandrine. Standing apart from the volume and Smith’s overall output of poetry, the compressed epic “The Hashish-Eater; or, The Apocalypse of Evil” remains an unparalleled masterpiece of cosmic invention and imagination. Its apparently endless pageant of wonders and episodes forms a veritable catalogue of things to come in Smith’s tales of 1929–1937.

The remarkable love poems in Ebony and Crystal find their complement on an extended scale in the even more remarkable love poems that make up most of Sandalwood, published in 1925, and concluding with nineteen translations from Les Fleurs du Mal of Baudelaire. After the cosmic and exotic splendors of The Star-Treader and Ebony and Crystal, and the oftentimes monumental tone of those two volumes; the tender, muted, vertumnal tone of this third major poetry collection comes as a surprise. Many of the poems are cast into beautiful forms of his own invention that suggest the old French rondeaus, triolets, ballades, and villanelles without actually being the same. The poems in Sandalwood are above all remarkable for their haunting, song-like effects, with all manner of refrain and echo-like devices. Like Ebony and Crystal, Sandalwood is a talismanic, touchstone volume. The nineteen poems from Baudelaire, as well as Smith’s Baudelairian translations elsewhere, establish Smith as a sovereign translator of the French genius, far superior to Edna St. Vincent Millay or even Arthur Symons.

Of Smith’s tales and extended poems in prose, they are prodigies of invention whose style is integrally one with their themes. They synthesize and extrapolate the backgrounds, concepts and stylistic elements of Smith’s three major early poetry collections. Smith’s unique type of science fiction (contributed mostly in the 1930s to Wonder Stories) represents a return to the cosmic-astronomic material of his very first volume of some twenty years earlier. As a perfectly logical consequence Smith’s tales employ the same immense vocabulary to be found in his poetry; a vocabulary used with a precision fully as creative and as masterly as that evident in his poems. Even the same or similar phrase-patterns and mannerisms reappear, forming in their entirety a worthy congener to “The Hashish-Eater.” What should one call them? Tales of death? Tales of splendor? Tales of beauty? Tales of deathly beauty? Tales of necromancy? Tales of demonology? Tales of magic? Tales of the supernatural? Tales of sorcery? Tales of metamorphosis? Tales of wonder? Tales of cosmic irony? Tales of deity, destiny and nemesis?

Perhaps, after all, the label “weird tales” serves as well as any.

Such prose demands an unusual and careful quality of reading to be fully grasped and appreciated. Merely regarded as short stories told in a heavily poetic style, Smith’s fictions would appear extraordinary. Regarded more exactly as extended poems in prose, his tales are nothing less than astonishing. To sustain a poem in prose for one or two pages is not an impossible feat; but to sustain one for ten, fifteen, even twenty pages, as Smith has undeniably done on many occasions, must be accounted a technical achievement of genius. Regarded as strange parables of love and death, or as quintessences of beauty, fear, love, wonder, ineffable strangeness, and much else; the tales of Clark Ashton Smith must in all truth take rank as something unique in the annals of prose fiction.

There are certain things in the works of a literary creator of which the industrious and systematic student can cite — themes, concepts, style, evolution, influence. But there is something which cannot be treated or understood in this way: the genius which manifests itself as the “sheer daemonic strangeness and fertility of conception” (to use Lovecraft’s happy and perceptive phrase). It is almost as if Smith were literally from another sphere than our own, inspired by some otherworldly genius or daemon. In the crystal of his mind’s eye Smith beheld strange, ineffable things — curious pageantries of doom, of death, of beauty, of love, of wonder, of destiny, of stars and planets, and of the cosmos. Let us therefore be grateful to him for the enchantment and ecstasy and revelation he created for kindred souls. And let us salute the passing of a generous and a noble spirit whose like we shall not see again. Perhaps somewhere in the long circle of eternity there will come a people who will take unhesitatingly to their hearts Smith’s brilliant creations in verse and in prose.