Written On the Hearts of Men: Swords From the Desert

Thursday, October 8, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

These fragmentary histories were jotted down on “date leaves, bits of leather, shoulder blades, stony tablets or the hearts of men.” But, put into words by men born and bred to war who spent most of their lives in the saddle, the written hadith have a real ring to them. Here we find no lengthy memoirs, no monastery-compiled chronicles, or histories written long after events. We have the word-of-mouth narrative of men who were on the scene.

– Harold Lamb, in a letter to Adventure magazine, concerning the traditions of the Arabs.

While Swords From the Desert (Bison Books) is a light-weight in page-count when matched against its hefty companion volume, Swords From the West, it definitely holds its own in quality. Weighing in at a “mere” three hundred and seven pages, it’s crammed full with the timeless adventure tales for which Harold Lamb should be more justly renowned.

Lamb scholar and series editor, Howard Andrew Jones, has written introductions for every Harold Lamb collection published by the University of Nebraska Press. In my opinion, the intro for Swords From the Desert is his best yet, mainly due to the new insights opened up to readers regarding the creator of all these classic stories, Harold Lamb. Within the introduction, Jones reveals that Lamb was an operative in Iran for the OSS during World War Two, gathering intelligence which helped thwart Axis subversion and facilitated the delivery of aid to our at-the-time allies, the Russians. Judging from the short reports excerpted, Lamb was quite possibly one of the most honorable and perceptive “spies” ever employed by American intelligence. After the war, the U.S. State Department still felt compelled to draw upon the well-traveled author’s expertise for several years.

Scott Oden, author and Friend of The Cimmerian, has written a most excellently succinct foreword to this volume, but I have discussed that elsewhere. Suffice it to say that Mr. Oden was the best man for the job, in my opinion.

The collection begins with “The Rogue’s Girl.” In his introduction, Jones sounds almost apologetic for the story’s inclusion, noting that it probably belonged in Swords From the West, but that this volume needed another tale far more than its massive companion did. I think this is a case of necessity bringing about a happy outcome. If most readers do as I did, and read “West” first, then this tale does a fine job of easing the reader from the more European viewpoint of that volume and into the Arab-centric stories featured in Swords From the Desert (though, upon reflection, I think that reading “Desert” then “West” would work about as well).

The “rogue’s girl” of the story is one Jeanne: a tough, red-haired denizen of medieval Paris’ Thieves’ Quarter. She, along with two companions, stumbles upon a dying man, one obviously of high station. Lamb depicts the two ruffians and their reactions in this manner…

Giron was one of the most skilled dice coggers and picklocks in the city, while his companion, Pied-à-Botte, was a veteran mockmonk and mumper. They felt aggrieved that the fallen man had not even a belt worth taking on him, and they had no mind to set their necks in a noose to help him in his dying.

Jeanne seeks aid from ibn Athir, an Arab physician and reputed alchemist who dwells nearby. They bring the wounded seigneur to his flat. Later, the girl asks a potion of the Arab. He mixes it, telling her that one of the ingredients is “star dust brought from the Egyptian desert where the heart of a flying star fell.” Interesting provenance, that, in light of modern discoveries.

The story proceeds, gathering momentum, intrigue and plot-twists as it goes. All in all, a fine tale to launch the collection. Jeanne is an engaging and resourceful heroine, and not the last we’ll encounter in this book. The plot and characters are reminiscient of those found in C.J. Cherryh’s An Angel With a Sword (1985), though I think it nearly impossible that Ms. Cherryh ever read this never-reprinted story from 1932.

“The Shield” moves the setting a big step towards the East and introduces the first main Arab protagonist of the collection, Khalil el Khadr. Khalil of Yamen is an old friend to your humble blogger. I first met him in the pages of Durandal, which short novel was my initial encounter with Lamb’s outstanding fiction. In that book, he was a capable and steadfast sword-brother to Sir Hugh. In “The Shield,” which forms a sort of “prequel” to Durandal, we find Khalil in Constantinople in 1204, on the eve of the siege launched by the “Franks” of the Fourth Crusade. Abou Asaid delineates Khalil’s character in these terms:

“Of well-sired horses and edged weapons and girls who walk with antelope grace — of such matters thou art conversant.”

Khalil encounters all three, and much besides, before he rides out the Damascus Gate of Constantinople, having witnessed the first fall of a city which had stood unvanquishable for a thousand years.

Now we arrive at what Howard Jones called “the jeweled center” of this collection: the tales of Daril ibn Athir. He is not one and the same as the “ibn Athir” in “The Rogue’s Girl,” (though that character is similar and perhaps a test-run for his later name-sake). In fact, as Jones points out, there seem to be two nearly identical, but different, “Daril ibn Athirs” within the three adventures below. We will cross that bridge when we come to it.

The first tale is “The Guest of Karadak.” We find Daril in the Nejd. He is a veteran (and very successful) warrior who, reaching the age of “fifty and eight,” has resolved “to see new lands and visit the throne rooms of far kings.” Reaching a mid-life crisis, Daril does not buy the medieval Islamic equivalent of a ‘Vette or a Winnebago. He adopts the title of hakim (ie.,  “physician”), for he has had much experience in the arts of healing during his years as a warrior and reaver, paradoxically. Withal, he does not forswear the sword. Instead, he gives away his non-essentials and sets out for the court of Jahangir, Light-of-the-Faith, Mogul of Ind.

“physician”), for he has had much experience in the arts of healing during his years as a warrior and reaver, paradoxically. Withal, he does not forswear the sword. Instead, he gives away his non-essentials and sets out for the court of Jahangir, Light-of-the-Faith, Mogul of Ind.

Daril’s talents as a healer are soon required once he disembarks in the Iranian port of Bandar Abbasi. He also draws the unwanted attention of Mirakhon Pasha, chief henchman to the ruler of Iran. Daril sets out across the desert, bound for Afghanistan, alone.

The hakim does not enjoy his solitude for long. By the time this tale reaches its thundering and bloody conclusion, Daril will see the mighty thrown down and justice measured out.

In “The Road to Kandahar,” we find that Daril ibn Athir has reached the midpoint of his journey, traversing the Valley of Thieves in Afghanistan. His small caravan is bushwhacked by ruffians (imagine that) who are beholden to al-Khimar, the Veiled One, a “prophet” bent upon stirring up the Pathans against the government of the Mogul, Jahangir.

The rest of this most excellent yarn is concerned with Daril seeking bloody vengeance upon the Veiled One and his minions. He is aided in this by Mahabat Khan, the viceroy of Jahangir.

There are those who see an influence upon Robert E. Howard’s “Black Colossus” emanating from “The Road to Kandahar” (Scott Oden is one). I see an influence, but I feel that it is minimal. Talbot Mundy depicted something similar to the Veiled One in his King — of the Khyber Rifles, only in Mundy’s case the hidden leader was a woman. In my opinion, Rohmer’s The Mask of Fu Manchu was the stronger influence (though Rohmer may have read “Kandahar”). All that said, “The Road to Kandahar” is a rippin’ yarn, full of blood and intrigue.

The third tale of Daril ibn Athir is “The Light of the Palace.” However, as Jones notes in his introduction, this “Daril ibn Athir” cannot be the same as the hakim in the two tales preceding. He sails directly to Hindustan and comes at the court of Jahangir from the south. He also meets and befriends Mahabat Khan with no sign of any previous acquaintance. Despite that, this Daril ibn Athir is nearly identical with his previous incarnation in every other respect.

It’s best not to worry overmuch regarding such continuity problems. It seems apparent that Harold Lamb was quite enamored with his Arab physician, but had a tale to tell that required a different backstory.

By the time “The Light of the Palace” is done, Daril has seen an emperor grovel and himself put the most powerful woman of his age in debt to him.

By the time “The Light of the Palace” is done, Daril has seen an emperor grovel and himself put the most powerful woman of his age in debt to him.

Until I’d received Swords From the Desert, I had yet to read any of the adventures of Daril ibn Athir. I am very glad to make his acquaintance. He is a man of compassion, but also one of honor who will not take it from anybody. It’s a pity that Lamb wrote no more tales of Daril, as he did of Khlit the Cossack.

The last two stories in Swords From the Desert are “The Way of the Girl” and “The Eighth Wife.” Both are fine tales and well worth a read. However, they also illustrate something that seems to be given slight regard when critics write about Harold Lamb (when that fortunate happenstance occurs). Namely, the fact that Mr. Lamb did not short-change his adventures (or his audience) when it came to strong women. In this volume alone we have Jeanne, Irene, Radha, Nadra and Zuleika. I am not forgetting Nur Mahal (also known as Nur Jahan), one of the beauties and powers of her time. Lamb devoted an entire historical novel to that personage. One that bears her name.

Just as “The Rogue’s Girl” led me into a world where the heroes saw with Arab eyes and spoke with an Arabic tongue, the appendix to Swords From the Desert brings Harold Lamb (and his readers) back to the tales found in its companion, Swords From the West. As was the case with the first adventure in this volume, many of the letters penned by Lamb that appear in the appendix are there in the cause of expediency, filling out an otherwise slim book. Still, I think their placement most fitting. Simply because Mr. Lamb wrote stories featuring Muslim heroes, never think for a moment that he ever thought less of the men who founded and literally “held the fort” to the bitter end in Outremer.

Lamb was no fan of the “debunking” regarding the Crusades, which was in fashion following the horrors of World War I. Here is an excerpt from a letter Harold wrote to Adventure magazine in early 1931:

That (the Crusaders) should lose their conquests was inevitable, when the new masses of Moslems, trained in the Mongol method of fighting, came against them from the East. At the end, they were dozens against hundreds — garrison posts against armies. Degenerate they were not.

Their devotion and their chivalry cast a light upon an age otherwise dark and grim and treacherous. No words of ours can alter what these men did. They reached the summit of daring. They drained the cup to the very dregs of suffering and shame. They followed the light of their star, until they died. And in spite of all that modern cynics can say, the Crusades will always remain a cherished memory.

Reading this book, I am once again struck by the impression (and I see no reason to ever change my opinion) of what a decent and even-handed man Harold Lamb was. He called ’em as he saw ’em, and he saw things better than most, in my opinion.

I will close with these words from Scott Oden’s fine introduction…

Welcome to the old Orient as Harold Lamb knew it.

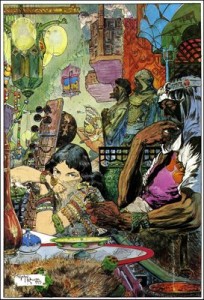

*Art by Edmund Dulac, Ken W. Kelly and Michael Wm. Kaluta.