The Call of Kathulos: Secret Oceans and Black Seas of Infinity

Thursday, February 19, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

In his first letter to H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard informed HPL that he considered the Man From Providence to be superior to Machen or Poe. In other words, the finest horror writer of them all. In another letter (ca. June 1931), Howard wrote to Lovecraft that “the three foremost weird masterpieces” were Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Machen’s “The Novel of the Black Seal” and last, but not least, “The Call of Cthulhu.” Thus, it is not surprising that some trace of REH’s enthusiasm for HPL’s landmark tale might be found in Howard’s own yarns.

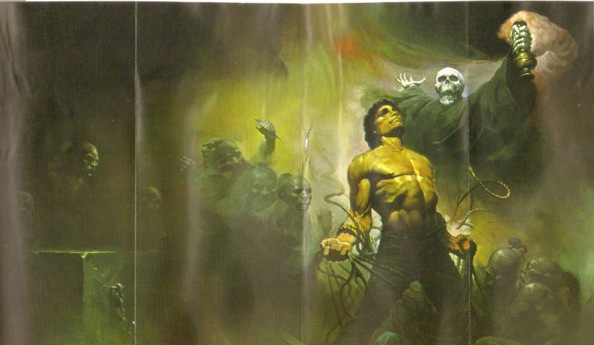

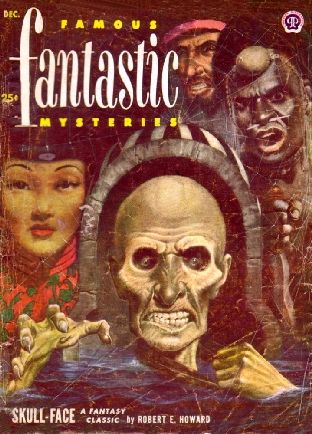

“Skull-Face” would seem to echo with whispers out of R’lyeh. That is not to say “The Call of Cthulhu” was Howard’s only source of inspiration for his tale of Kathulos of Atlantis. Far from it. Over at the Official Robert E. Howard Forum, I went into some depth regarding the influence of Sax Rohmer’s writings upon “Skull-Face.” As I’ll demonstrate below, it appears that a Rohmer novel might have exerted some influence upon “The Call of Cthulhu” as well.

“Skull-Face” and “The Call of Cthulhu” both begin with revelatory dreams. Costigan’s is a “dream” induced by hashish. Through the haze of it he glimpses the visage of “the Master,” Kathulos of Atlantis. The dreams of Henry Wilcox, wherein the artist sees visions of Cthulhu, Lord of R’lyeh, are the catalyst that sends Professor Angell off on his quest to find out the truth behind the Cthulhu cult. Through dreams, Cthulhu holds Wilcox in “mental bondage,” and exerts a malign influence upon other “sensitives” throughout the world. Kathulos is the hidden master of the House of Dreams, using drugs to control many of his servants and is also a wielder of great mesmeric power, holding minions like Zuleika in thrall. On the last page of “Skull-Face”, Stephen Costigan admits, “At night I dream of them,” referring to Kathulos’ still-sunken brethren. I can think of no other major work of fiction by Robert E. Howard which is so pervaded by dreams and dream-imagery.

Like “The Call of Cthulhu,” “Skull-Face” is redolent with references to letters, documents and newspapers. Other than the “The Riot at Bucksnort” and “The Dead Remember” (both written at a much later period), the use of such in Howard’s works is quite rare. Rohmer employed epistolary devices rather sparingly as well.

“Skull-Face” is also fraught with “investigators” of every stripe. Sir Frenton (as well as Schuyler) makes a pretty good stand-in for Professor Webb in “The Call of Cthulhu.” John Gordon combines many of the functions of Thurston and Inspector LeGrasse admirably. Morley and Rokoff, like Angell and Johansen, die because they “know too much.”

World-spanning, murderous cults are a central feature of both stories. Both tales convey the impression of dark, unseen forces seething just below the surface. Each cult has its distinctive, grim symbol. The lackeys of Kathulos all bear the Mark of the Scorpion. The devotees of Cthulhu always seem to  have a green-stone eidolon of their deity around somewhere. Old Castro speaks of his “undying masters” in China, while Rokoff was permanently silenced before he could reveal what he learned in Mongolia. Both cults promise a “dark empire” for the faithful, one where believers can be “free and wild and beyond good and evil.” The two cults also seem to draw much of their cannon-fodder from the Caribbean and west Africa, as well as other colonialized peoples.

have a green-stone eidolon of their deity around somewhere. Old Castro speaks of his “undying masters” in China, while Rokoff was permanently silenced before he could reveal what he learned in Mongolia. Both cults promise a “dark empire” for the faithful, one where believers can be “free and wild and beyond good and evil.” The two cults also seem to draw much of their cannon-fodder from the Caribbean and west Africa, as well as other colonialized peoples.

“Voodoo” ceremonies that are bloodily interrupted by the protagonists are set-pieces in both tales, though not the climactic battles in either. The “screech and roar” of “black leopards” that Costigan hears when he takes on Santiago’s congregation is paralled by the “(a)nimal fury and orgiastic license” that LeGrasse encounters in that unholy Louisiana bayou. Both Santiago and Old Castro seem to hail from the Caribbean. From his description, Santiago might be kin to Saul Stark, tracing his lineage back to the “black kings of Atlantis.” Castro, on the other hand, is a mestizo. It might be, like a better-known Castro, that the secret priest of Cthulhu hails from Cuba.

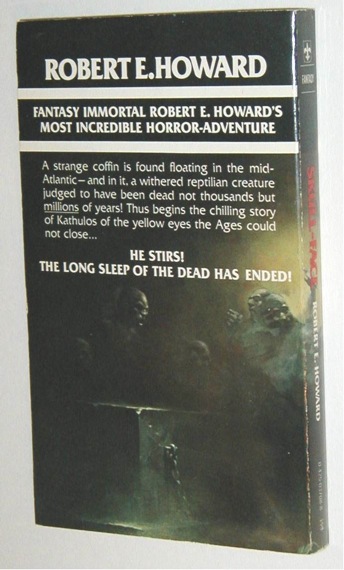

Cuba is the setting for Rohmer’s 1921 novel, Bat Wing. We know from Dan Harms’ The Necronomicon Files that HPL read Bat Wing not long before he wrote “The Call of Cthulhu.” We also know that REH had Rohmer’s novel on his own bookshelf. One chapter of the book is named “The Call of M’Kombo.” The “M’Kombo” referred to is a Beninese houngan who “calls” and influences his victims through their dreams. Sound familiar?

Both tales also share in common crucial “shipboard scenes.” In the case of “The Call of Cthulhu,” the European crew of the Emma is attacked by the “half-caste” crew of the Alert. The men of the Emma triumph, but not before their own ship is sunk. Sailing the captured schooner, the crew of the Emma then encounter Cthulhu. In “Skull-Face”, Von Lorfmon’s ship finds the sarcophagus of Kathulos off Senegal (shades of HPL’s “Brava Portuguese” and not far from Benin). The crew, made up of Greeks and Africans of various persuasions, could almost be an Atlantic version of the combined crews of the Emma and the Alert. While similar in many respects, the two scenes differ in a crucial way. Lovecraft’s scene depicts the end of Cthulhu’s bid to dominate the world, while Howard uses his chapter to show the beginning of Kathulos’ efforts to bring back the glories of Imperial Atlantis.

Not only do the advents of Kathulos and Cthulhu share much in common, but the very titles of the chapters in which the two monsters rise from the briny deep recall each other to a remarkable degree. In “The Call of Cthulhu,” the title of the chapter in which the crew of the Emma discovers Cthulhu is “The Madness From the Sea.” In “Skull-Face,” the chapter in which Von Lorfmon discovers Kathulos is entitled “The Dead Man From the Sea” (it’s almost an anagram of HPL’s title). Other headings from “Skull-Face” that could have been plugged into “The Call of Cthulhu” are “Black Wisdom,” “Ancient Horror” and “The Black Empire.” Nor would one of the epithets of Kathulos, “The Son of the Ocean,” seem incongruous if applied to the Lord of R’lyeh.

For me, none of the points above really registered until I happened to reread the last chapter of “Skull-Face.” In it, John Gordon delivers what is more or less a soliloquy that, in my estimation, basically restates many of the points in the first and penultimate paragraphs of “The Call of Cthulhu.” For instance, Gordon says, “I have come to believe that mankind eternally hovers on the brinks of secret oceans of which it knows nothing.” Compare that with the second sentence from “The Call of Cthulhu”: “We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity.” Gordon goes on to say, “We have been face to face with an ancient horror with a fear too dark and mysterious for the human brain to cope with.” He concludes that, “The universe was not made for humanity alone.” Consider those sentiments in light of HPL’s much-quoted line about “correlated contents” and also with, “some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light.” Lovecraft’s narrator, Thurston, says that, “I have looked upon all that the universe has to hold of horror, and even the skies of spring and the flowers of summer must ever afterward be poison to me.” When Costigan informs Gordon that he possesses a new-found appreciation for life and love, Gordon advises the American that, “The best thing is to forget all that dark interlude, for in that course lies light and happiness.”

In all of the above, I am in no way seeking to deny Robert E. Howard’s innate genius, nor am I in any way attempting to refute all those who have noted the influence of Sax Rohmer upon REH’s “Skull-Face.” I myself have spent quite a bit of time detailing Rohmer’s probable influence over on the REH Forum. However, in my opinion, it appears that “The Call of Cthulhu” was a major source of inspiration for the novella that Lovecraft himself singled out as “powerful” and “memorable.” As he so often did, Robert E. Howard took elements from authors he admired and transmuted them into a thunderous, blood-soaked yarn as only he could tell.

*I’d like to thank [redacted] for his suggestions concerning “grim symbology.”