Merritt’s The Ship of Ishtar From Planet Stories (Paizo)

Monday, December 7, 2009

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

I enjoyed the rare and original fantasy of [The Ship of Ishtar], and have kept it longer than I should otherwise, for the sake of re-reading certain passages that were highly poetic and imaginative. Merritt has an authentic magic, as well as an inexhaustible imagination.

Klarkash-Ton, as usual, was right on the money. As one who recognized a kindred genius and spirit in Robert E. Howard long before the majority of his peers, CAS knew magic, poetry and imagination when he beheld it.

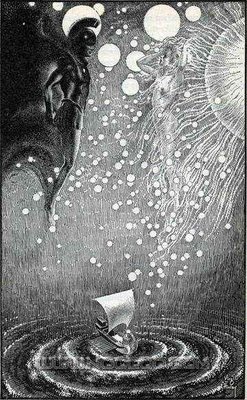

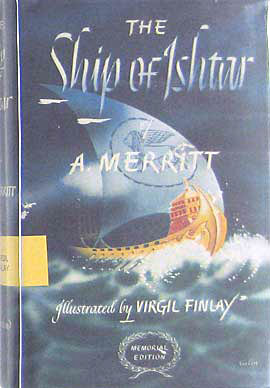

My copy of the Paizo edition of The Ship of Ishtar came in the other day. Despite the fact that I own three other imprints of this fantasy classic, I’d been anticipating the delivery of this edition for months. Erik Mona and his crack team of pulp-hounds at Planet Stories have outdone themselves on this project. Going back to the 1949 Borden “Memorial Edition,” they have issued the most complete text in sixty years, included all of the classic Virgil Finlay illustrations from two different editions (something never done before) and allowed Merritt (and CAS and REH and HPL) fan, Tim Powers, to write the introduction.

Powers, a noted author in his own right, was an inspired choice. The man gets Merritt. His introduction, entitled, “On These Strange Seas In This Strange World,” is one of the best analyses and tributes devoted to The Ship of Ishtar that I have read. Here’s one passage:

This novel, like the Ship of Ishtar itself, is timeless — the opposite of timely — and in fact it may not be possible to write a book like this in these present times. Somehow, in the early 1920s, Merritt managed to write a genuinely pagan book, one that simply didn’t deal with, but assumed, the pre-Christian fatalist dualism, with its particular loyalties and indifferent cruelties. A modern writer would not let Kenton deal with slaves and conquered crews the way he does, and would be constantly aware of Freud and political correctness. A modern writer, that is to say, would not be able to unselfconsciously let his story play out naturally, with no placatory gestures toward modern sensibilities.

Exactly. When The Ship of Ishtar hit the stands in 1924 between the covers of Argosy All-Story magazine, nothing like it had ever seen print in American popular culture. Despite being drenched in blood, sex and the supernatural, the American public took to the novel like Islam to the desert. Merrit’s ground-breaking work would eventually go through twenty-plus printings and sell millions before the end of the twentieth century. It would seem almost certain that Robert E. Howard, a long-time and faithful reader of Argosy, was one of those millions of readers.

The novel begins in a Park Avenue penthouse. There we find John Kenton. The scion of a wealthy family, Kenton was a playboy archaeologist before he volunteered to serve in the Great War. He came back from Belleau Wood as damaged goods.

Hag-ridden by a great restlessness, thus he had returned; his attitude toward life, like thousands of others, profoundly changed. The world he knew had lost its zest; the one in which he could be happy he did not know where to find; he could not formulate even what it might be.

As Steve Tompkins once noted, there is an existential gulf that separates pre-WWI writers like Wells and Burroughs from their post-WWI literary descendents. A. Merritt bridged that gulf, and one can read sentiments similar to Kenton’s voiced by Stephen Costigan in REH’s “Skull-Face,” which was written four years after the debut of The Ship of Ishtar.

Kenton soon finds himself mystically transported from Manhattan to the deck of the Ship of Ishtar. It is but the first of several seemingly capricious translations he will suffer, being swept back and forth by forces beyond his control. Some readers have criticized Merritt for this, but there was definitely a method behind his madness. Merritt used this narrative device to propel the tale forward at break-neck speed. Kenton (and the reader) continually finds himself in the thick of the action, only to then discover himself back in his penthouse. Upon his return, events have always moved forward in his absence, forcing him to adapt to and conquer his environment. The first time Kenton is returned to our world, he finds the clock still chiming the same hour as when he left. We see the same sort of temporal relativity in Howard’s Kull story, “The Striking of the Gong,” which was written several years later.

Returning to the timeless World of the Ship, Kenton learns that the Ship of Ishtar is a floating battlefield where the priestess of Ishtar, Sharane, and the priest of Nergal, Klaneth, wage a millenia-old struggle as proxies for their respective deities. Kenton ends up at cross-purposes with the Nergalite faction, killing several priests (quite bloodily) with his bare hands before being chained to an oar-bench (just as Kull and Conan would be later). His partner in misery is a Viking named Sigurd. They swear blood-brotherhood and plot the downfall of their enslavers. Kenton, no pansy to begin with, becomes born-again hard, his rage and hatred tempering his body and soul:

As though he had tapped some ancient spring, some still pool of archaic indifference both to life and death, the cold current ran through him. And never again, although then he knew it not, was Kenton to feel for either life or death that respect or fear which, in his own world, were their legitimate shadows. All that he then realized was that whatever spirit of weakness within him there had been — was gone.

Help comes in the form of Gigi, a black-eyed, swarthy “stunted giant” (shades of Bran Mak Morn’s Grom) and Zubran, a sardonic Persian. Both men had been tricked into serving Klaneth and wish an end to their captivity. Between the two of them, they effect Kenton’s escape, but he is then suddenly swept back to our world.

This brings up the other purpose for what a few consider an intrusive plot device. Kenton finds himself back in his Manhattan penthouse, free, still rich and in the best shape of his life. Why go back? This choice is proffered to Kenton several times in the novel and it is obviously not an accident on Merritt’s part. Life, luxury, filthy lucre. What’s not to like? What does the World of the Ship present as a counter-offer? A near certainty of pain and bloody death. Also, brotherhood, vengeance, a life worth living and the finest woman in all of fantasy literature: Sharane, flame-haired priestess of Ishtar. Kenton never hesitates. If that isn’t the decision of a (proto-) Howardian hero, I don’t know what is.

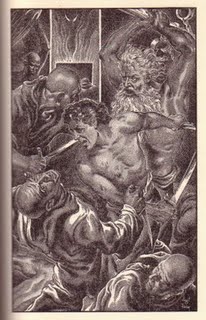

Kenton returns and frees Sigurd the Viking. Reaching the deck, they are

Kenton and Sigurd

confronted by Nergal’s acolytes:

There were eight of the black robes facing them. The Norseman’s oar struck, shattering the skull of one like an egg shell. Before he could raise it again two of the priests had darted in upon him, stabbing, thrusting with their spears. Kenton’s sword swept down, bit deep into the bone of an arm…

Merritt was always justly famed for his action sequences.

In all honesty, there is just too much coolness to cover in one blog entry. Bottom line: buy this book. Perhaps then you’ll see what Clark Ashton Smith, C.L. Moore, Robert E. Howard, Edmond Hamilton, H.P. Lovecraft, Leigh Brackett, Michael Moorcock, Gardner Fox, Jack Williamson, Karl Edward Wagner, Tim Powers and others saw in Merritt and The Ship of Ishtar. Speaking of Mr. Powers, I’ll end this review with another excerpt from Tim Powers’ “On These Strange Seas In This Strange World”:

There’s no self-conscious auctorial irony here, no post-modern deflation of drama. This is pure adventure — like the protagonist John Kenton, the reader himself is swept out of his modern room into the tumultuous world where the goddess Ishtar and the god Nergal are perpetually in conflict, and the reader experiences the action, rather than simply notes it, as Kenton fights his way up from being a despised galley-slave to winning the priestess Sharane and ultimately to challenge the gods.

*Art by Virgil Finlay