Lupoff and Chabon Talk John Carter of Mars at ERBzine

Friday, March 19, 2010

posted by Deuce Richardson

Print This Post

Print This Post

Those TC readers who have bothered to check the links I’ve posted in my ERB-related entries probably already suspect that I hold Bill Hillman’s ERBzine website in high regard. Such suspicions would not be unfounded. Mr. Hillman hath builded a mighty temple to the Lord of Tarzana that hangs amidst the æther in erudite splendor.

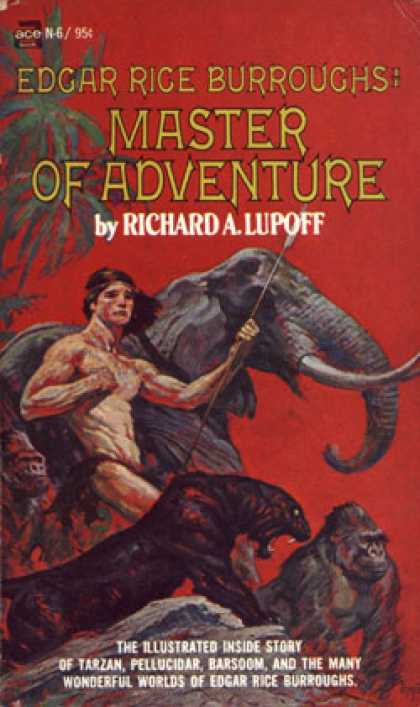

This last January, Bill presented to his readership a most excellent symposium betwixt two major Edgar Rice Burroughs fans: Richard Lupoff and Michael Chabon. Mr. Lupoff, a long-time Friend of The Cimmerian, authored the first serious look at ERB and his works, Master of Adventure, as well as editing ERB volumes for Canaveral Press. Michael Chabon (a past recipient of the Pulitzer Prize) is on record as being a fan of of Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber. In his ERBzine interview (conducted by Lupoff), Chabon reveals his life-long love for the fiction of Burroughs.

Chabon starts off the interview by telling Lupoff about when he first moved to LA in the mid-’90s and tried to get his screenplay, The Martian Agent, filmed. Turns out that one of the many auctorial hats Chabon wears is that of “steampunk author.” The basic premise of the screenplay was that the British Empire managed (through precocious technology) to reach the Red Planet in the 1890s.

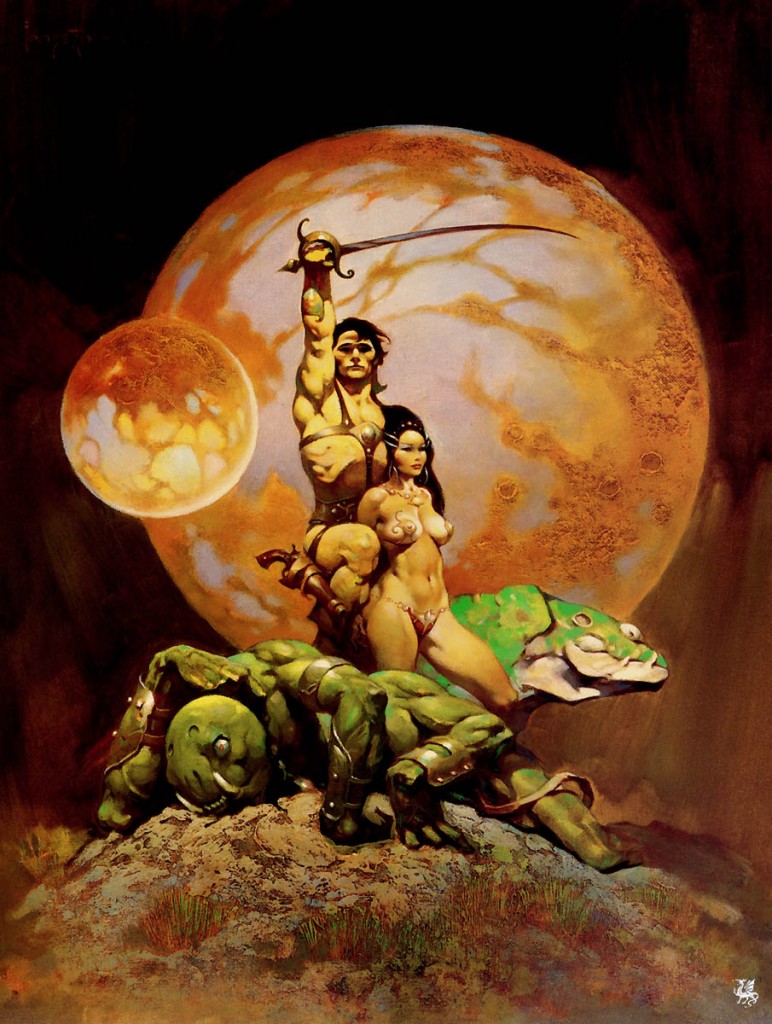

The project was optioned by Fox and FX spec work was done by ILM, but the whole affair was stillborn when the annointed director, Jan de Bont, fell from grace. However, in a happenstance worthy of a Burroughs novel, Chabon met one of the former ILM guys who’d worked on the project at a Christmas party in 2008. By way of that chance encounter, Chabon was put in touch with Andrew Stanton, the director for the Disney production of John Carter of Mars. Faster than a Barsoomian panthan could shout, “Kaor!”, Chabon was doing the rewrite on Stanton’s and Mark Andrews’ script for the John Carter project.

According to Chabon, the script was already in “good shape” when he got to it. When asked by Lupoff as to whether the script would be closely based on ERB’s first novel, MC explained it this way:

I guess I’d say if all goes as planned, the first three films — were there to be three films — would more or less cover the same ground as the first three novels in terms of where we would end up, and what would be known to be true.

But the books — they’re serialized novels, from a pulp magazine in 1912 and 1915 or whenever. They weren’t really written with a two-hour, 21st-century major studio motion picture in mind. There are changes that have to be made. There’s not a precise one to one correspondence, as with the Harry Potters — it’s not like that. Nor is it a complete departure, not by any means. The idea was to gather up the important threads of story from all of the first three novels and weave them into a coherent, three part whole, yet with each part standing on its own. As if ERB had conceived the first three books as a trilogy, which he did not, since even with his wild imagination he had no reason to believe, as he was writing the first John Carter novel, that there would ever be a second.

Dick Lupoff then goes on to note that, after a recent rereading of A Princess of Mars, he didn’t find it that good of a novel. Chabon basically concurs. I, myself, concur to a certain extent. As a novel, “APoM” has many faults. However, it should be kept in mind that (other than the only-recently published Minidoka) A Princess of Mars was the first work of fiction that ERB ever put to paper. As a boy, Burroughs was actively discouraged from any activity that smacked of imagination by his domineering father. In fact, an argument could be made that Robert E. Howard was proffered more encouragement in his formative years than ERB ever was. So (as Chabon notes), Burroughs poured out all of that stifled creativity into his first novel. Some elements, like Barsoomian telepathy and “radium guns” with ranges over fifty miles, were quietly dropped (on the whole) by ERB when he returned to Barsoom in Gods of Mars and later novels. In my personal opinion, a truly great editor could have sent back the manuscript and requested Burroughs change or tighten up the elements that bother people like Lupoff, Chabon and myself here in the twenty-first century.

Newell Metcalf, the editor for All-Story Magazine, wasn’t up to such a task, but he apparently requested some changes (several of which were rescinded for book publication). Still, Metcalf deserves a place at the Table of Editors in literary Valhalla for recognizing that he had a storytelling genius on his hands. For all his faults, ERB could spin a yarn. Just as importantly, Burroughs was possessed of an imagination of almost unprecedented fertility. With the merest of terrestrial inspirations, the Man From Tarzana could extrapolate worlds nearly undreamt of by previous authors and set therein tales which still stir the imaginations and pluck the heart-strings of the less-earthbound among us today.

For those following along at home, we have now reached the point in the Lupoff-Chabon interview that I hold in slightest regard. Firstly, Lupoff cocks off something about Barsoomian “ray guns,” artifacts which never existed on ERB’s Mars. Apparently emboldened by Mr. Lupoff’s blunder, Chabon goes on to say that ERB’s Tharks were inspired by Afghani tribesmen from the works of Kipling. Lupoff then volleys back that faux pas by implying that the British Empire never ever defeated the Afghans.

In all fairness, Chabon correctly calls Barsoomian firearms “radium rifles” (essentially, guns firing explosive-tip shells, according to ERB) in his response to Lupoff. However, MC then goes on to compound Lupoff’s technological error by making a major ethnological one of his own. “Afghani tribesmen”? Really? Exactly where is this stated by Edgar Rice Burroughs? In my humble opinion, when one speculates on the sources for freshly-wrought peoples/species in the works of an author of imaginative fiction, it is always best to look closest to home first. At the very least, examine what peoples/species profoundly interested said author.

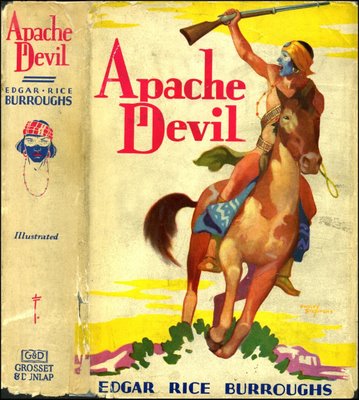

To the best of my knowledge, ERB never once mentioned Afghan tribesmen in his fiction nor in his correspondence. On the other hand, he chased Geronimo’s Apaches with the 7th Cavalry in the late 1890s. In case either esteemed author forgot, I’ll remind them that A Princess of Mars begins with a hostile encounter involving Apaches. Burroughs’ Tharks are a caricature of Apache culture as Edgar Rice Burroughs saw it at the dawn of the twentieth century (he later made amends in Apache Devil and The War Chief). Such is my opinion and I stand by it.

Then Lupoff opines that the British “got whipped” by the Aghans. This comment is presented without modifiers. Lupoff and Chabon seem to think that the First Anglo-Afghan War ended in January of 1842 with the massacre at Gandamak, the casualties of which were overwhelmingly civilians (and the result of a broken treaty on the part of the Afghans). They appear to forget (or simply not know) that the army of the British East India Company returned and accomplished nearly all of its objectives by the end of 1842.

Chabon mentions “gatling guns” (which the British never used in Afghanistan to the best of my knowledge). Chabon couldn’t be referring to the Second Anglo-Afghan War because the British Army didn’t begin employing the similar “Maxim gun” until 1885. Once again, in the end, the British did not get “their asses handed to them” (as Chabon states).

Lupoff and Chabon both seem to off-handedly imply that the goal of the British East India Company (and later, the British Empire) during the nineteenth century was to annex Afghanistan (as opposed to neutralizing it as a threat and preventing Russia from taking it over). I’d like to see them back up that implication with anything concrete. I wouldn’t be disputing their comments so vigorously except for the fact that…

A little later in the interview, the two authors return to the subject of “imperialism” in a big way. Mr. Lupoff starts it off by noting that Wells’ War of the Worlds was really about the British Empire in India (news to me). Chabon’s reply is this:

Adventure fiction as we most commonly understand it is about imperialism in one degree or another. All the great archetypes, the prototypes from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan and John Carter, H. R. Haggard, and all the way up to, even the western novel, The Virginian, all the way through to James Bond — they’re all about empire — the interaction between empires and colonies as they are colonized.

My jaw dropped whan I read that. I guess all “modern adventure fiction” should be shoved into a box (made of some imported, colonial wood, I assume) stenciled with the one, chilling word: “Imperialism.” Tarzan was born and grew up amongst hominids in an area of Africa not controlled by the homeland of his parents (ie, the British Empire). He frequently pointed out the foibles of his (genetic) countrymen and seemed to prefer his native surroundings (and the peoples thereof). John Carter wasn’t born on Barsoom, but he essentially “went native” (and sided against the “white” Therns). David Innes frequently scoffed at the attempts of Abner Perry to import concepts from the “Outer World” to Pellucidar.

All of the fiction that Chabon refers to was written by authors in a Western cultural milieu during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One facet of that milieu was “imperialism” (however one might like to define it). Chabon seems to ignore the fact that those writers were also working in a tradition stretching back to Homer. Was Odysseus (in The Odyssey) an “imperialist”? Was Cuchullain? How about Grettir the Strong? Is every wandering protagonist in the Western cultural tradition an “imperialist”? Is anyone (of European background) who strides beyond the fields he or she knows to find adventure and face adversity a secret agent of “imperialism”? Does this rubric not also apply to adventurers in, say, Muslim or Chinese literature? Just some wonderings by this humble blogger.

Back on more amenable ground… Mssrs. Chabon and Lupoff also discuss Edgar Rice Burroughs’ inveterate use of subtle (and, sometimes, not so subtle) satire in his fiction. Lupoff noted this facet of Burroughs in Master of Adventure (which book I recommend). Twenty years before I read that illuminating and ground-breaking text, while still a grade-schooler, it was obvious to me that ERB was using the freedom provided by the genre of imaginative fiction to comment upon the human condition and the foibles thereof. Monoliterate aficionados of “mainstream” or “realistic” fiction just do not seem able to wrap their brains around the idea that “weird” or “speculative” fiction allows authors to isolate and exaggerate certain concepts and thereby examine them more clearly. Why didn’t Swift simply send Gulliver wandering around Britain or Ireland? Why did Lewis Carroll dispatch Alice through the Looking Glass? I would think the answer is obvious.

Please, gentle readers, do not be put off by my quibblings and forego reading the interview. I may have disagreements with parts of it, but, on the whole, it is well worth your while. As Mr. Lupoff announces at the end of it all: “Anyway… I’m so happy we’ve done this.” Today, sixty years after ERB’s passing, we’re all just brothers in the fraternity he created.