Lonely Mountain, Crowded Expectations; Or, Prelude as Successor

Saturday, October 25, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

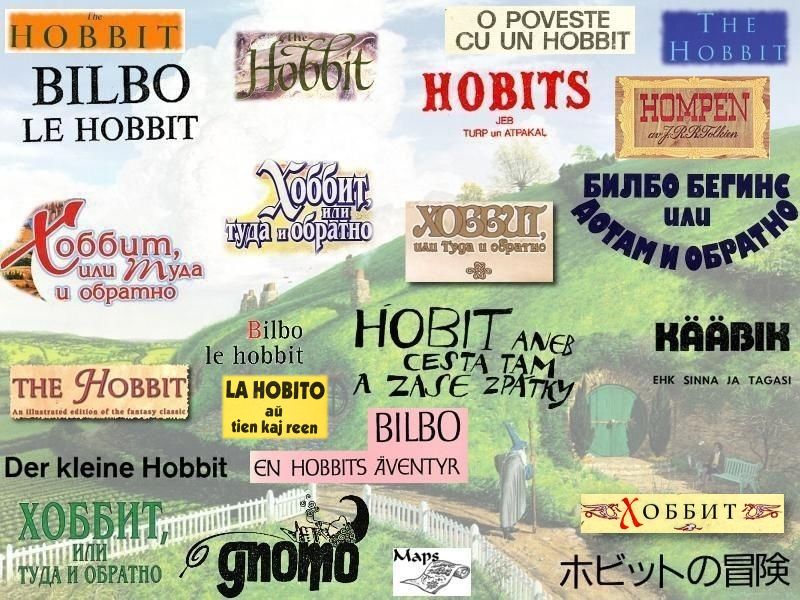

Too many of my waking hours are given over to thinking about the Hobbit films due in December of 2011 and December of 2012; no sooner is my attention directed elsewhere than the voluble and value-adding Guillermo del Toro is interviewed again and — sproing! — my thoughts ricochet back to the movies he’s about to make. After all, it won’t hurt to have something to which I can look forward after moving to a Hooverville and while shuffling along on Hoover leather (The Internet is of course rendering Hoover blankets obsolete). Admittedly my druthers would have been a movie about the wrath of Fëanor, the wanderings of Húrin, the fall of Gondolin, or the last days of Númenor. But any Silmarillion-based movie would be hobbit-free, and hobbits shift units and sell tickets. Me, I tolerate rather than love them, although I would never go as far as Michael Moorcock, who quipped of Sauron, “Anyone who hates hobbits can’t be all bad,” or the younger Charles Saunders, who once expressed (he has since mellowed) a profound relief that there were no black hobbits. Admiration and affection for Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin I have aplenty; I just don’t love hobbits qua hobbits. But many do; adoption agencies that offered hobbit orphans would be forced to hire extra security for crowd control.

In his magisterial two-volume The History of the Hobbit John D. Rateliff backhands “critics who would prefer The Hobbit to conform to and resemble its sequel in every possible detail.” Guilty as charged; I try and mostly succeed in cherishing the book for its own self, and almost fainted when, in the dealers’ room at the 2006 World Fantasy Convention in Austin, I came face to face with a first edition 1937 Hobbit. But reading-sequence is destiny, and I first read the “enchanting prelude” in the spring of 1971, a few weeks after hurtling through The Lord of the Rings. As a result, what really got my pulse pounding like hammers in dwarven smithies were what Tolkien, looking back from the vantage point of LOTR‘s Second Edition, described as “references to the older matter: Elrond, Gondolin, the High-elves, and the orcs, and glimpses that had arisen, unbidden, of things higher or deeper or darker than [The Hobbit‘s] surface: Durin, Moria, Gandalf, the Necromancer, the Ring.” Although not immune to the beguilingly unique properties of The Hobbit, I responded the most to premonitions and foreshadowings of the later work, the design features of the Eohippus from which the later Arabian stallion could be extrapolated. So for me “higher or deeper or darker” is the way to go in the impending movies, because so many millions of filmgoers will plant themselves in multiplex seats as vividly aware of the previously-viewed-even-if-chronologically-“later” Peter Jackson films as I was of the previously-read-although-chronologically-“later” LOTR back in 1971. Some of the posts at Tolkien-oriented and other genre sites reflect apprehension that Guillermo del Toro and Peter Jackson will “spectacularize” or “bombastify” the source material, inflate a children’s classic into a swollen epic, and such protectiveness is laudable, but barring an Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind-style memory-scrub, the audience can’t be made to unsee The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. Ergo higher, deeper, darker.

Del Toro and Jackson are both sometime horrormeisters, and can be expected to seize upon non-kid-lit moments like the orc-head impaled on Beorn’s gate and the warg-skin nailed to a nearby tree after the shapeshifter’s night reconnaissance. The “creaking and hissing” of the Mirkwood spiders as they gloat over their captives is right up del Toro’s alley as well: “What nasty thick skins they have to be sure, but I’ll wager there is good juice inside.” Do spiders have lips? If so, the words “good juice inside” should be pronounced with lipsmacking relish.

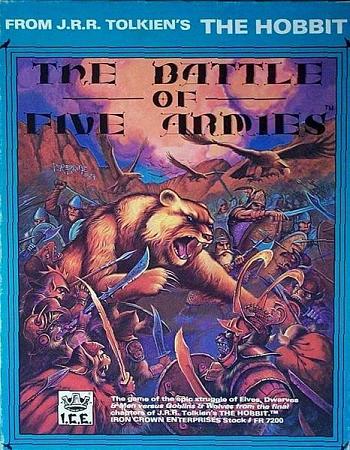

And given the blockbuster imperative of more is more (with the corollary that less is less, and therefore unacceptable), the visitation of Smaug’s wrath on Esgaroth, a few thrilling paragraphs in JRRT’s telling, is certain to escalate into something like the February 1945 Dresden firestorm. By higher, deeper, and darker I don’t mean a half hour of pyrotechnics or a metal-meets-meat approach to the Battle of Five Armies à la Stephen Pressfield or Paul Kearney’s The Ten Thousand. Nor, although Tolkien himself marveled, in his December 16, 1937 letter to publisher Stanley Unwin, at how “even Sauron the terrible peeped over the edge” of what “began as a comic tale,” am I angling for an unconscionable text-deviation like issuing Smaug a palantír so he can be in constant communication with the Dark Lord in Dol Guldur throughout the first of the new movies. Instead, my agenda is filling the vacancies that will be left by aspects of The Hobbit that won’t translate to any adaptation other than the 1977 Rankin/Bass Kinderspiel.

The narration, for starters. In later years Tolkien made no secret of his misgivings about the tendency on the part of the book’s narrator to talk down to readers and, if a story in print rather than onstage or onscreen can be said to possess a fourth wall, break that wall. John D. Rateliff’s Mr. Baggins is doughty in defense of the narrator’s voice as “an essential element in establishing the tone of the story and hence of the book’s success,” one that makes the narrator himself, both playful and at pains to capture and retain the attention of the children who in effect are listening to him, “one of the most important characters in the tale.” But he won’t be a character in the movie; an attempt via voiceover to present him as one would be an irreparable alienation effect for too much of the audience.

With a narrator absconditus, the 2 new films will need other sources of information (Notice I don’t say exposition; the Medvedites of the world are convinced Hollywood hates the word patriotism, but Hollywood — even Hollywood outsourced to Wellington — really, really hates the word exposition). What I’m after here might be demonstrable by turning to the two songs of the very first set piece in The Hobbit, when the thirteen dwarves stop in at Bilbo’s hobbit-hole. The first is a washing-up song, in which the guests appall their host with mock threats to break his glassware, annihilate his crockery, and render his larder unusable. Although a child-delighter, no way that song goes into the movie; too Seussian. But the second song, “Far Over the Misty Mountains Cold” — not to be confused with Led Zep’s “Misty Mountain Hop” — which sweeps the previously recalcitrant Bilbo “away into dark lands under strange moons” and conjures for him the depredations of Smaug and the sad comedown of dispossession — that’s a challenge I’m betting composer Howard Shore and probable lyricist Philippa Boyens will be unable to resist (The “places deep, where dark things sleep” mentioned in “Far Over” always read to me like a presentiment of the Balrog and the Matter of Moria, although the drafts in The Return of the Shadow: Part One of The History of The Lord of the Rings indicate that Tolkien’s original intended foe for Gandalf on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm was “merely” a Black Rider, not a Balrog). The two songs constitute something of a tonal tug-of-war, one noticed by John Rateliff as well: “Against the comedy of confused expectations on all sides is set this poem describing the lost kingdom of the dwarves and its fiery destruction by the dragon.”

Much of what I’m looking for in terms of higher, deeper, darker comes clad in dwarf-mail. Whereas the Rings films contained multiple hobbits but only one Dwarf, the Hobbit films will contain multiple Dwarves but only one hobbit, and therefore afford an opportunity for a do-over of sorts. Although John Howe, Alan Lee, and the production designers triumphed with the look and feel of Moria in The Fellowship of the Ring — the greatest and deepest of dwarrowdelfs, implying an entire chthonic civilization — Gimli’s chief function in the Jacksonian scheme of things was to sit down on a succession of whoopee cushions and intercept one custard pie after another with his face; a shame, as John Rhys-Davies easily sold the serious dialogue he was given, and could have made, for example, the character’s Glittering Caves of Aglarond prose poem in The Two Towers sing. But with thirteen Dwarves (although some of them will be but stumpy extras; Tolkien wasn’t exactly even-handed in his sharing-out of speaking roles) plus the army that arrives for the climax, del Toro should be able to convey the pitted rockface of their culture and collective experience much more thoroughly (One of the delights of Douglas A. Anderson’s The Annotated Hobbit is a collection of 1938 American reviews of Tolkien’s book, two of which invoke Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, a 1937 release, but an association that would have mortified the Disneyphobic Tolkien). Return to Bag-End, part the second of Rateliff’s The History of The Hobbit, includes a resonant sentence cut from the Prefatory Note included in the book’s Second Edition in 1951: “Dwarves had already known a long and troublous history in the world before the days of Thror, and when he wrote of old he meant it: in the ancient past, remembered still in the songs of lore that the dwarf-kin sang in their secret tongue at feasts to which none but dwarves were bidden.”

If Dwarf-lore must remain a feast to which none but Dwarves are bidden, at least the chance to journey in company with thirteen of them will permit us to catch a little of the smell and savor of that feast, learn a little of the “long and troublous” history. Elsewhere, in the Appendices of The Return of the King, Tolkien terms the Dwarves “a tough, thrawn race for the most part, secretive, laborious, retentive of the memory of injuries (and of benefits), lovers of stones, of gems, of things that take shape under the hands of the craftsman rather than things that live by their own life.” My ten-year-old self hotfooted it to several dictionaries upon encountering that winningly flinty old word thrawn, the Scottishness of which now seems to anticipate the accent Rhys Davies adopted for Gimli in the Peter Jackson films; a case can be made that no finer example of the mot juste exists in all of fantasy. Tolkien’s Dwarves don’t necessarily make the best first impression, nor did they endear themselves to him when he was initially sketching his legendarium, as The Book of Lost Tales documents. They’re a dour, only-truly-at-home-underground bunch; Gandalf displays a barbed insight into Dwarven values in “the Quest of Erebor” when Glóin disparages hobbits: “I suppose you think them simple because they are generous and do not haggle; and think them timid because you never sell them any weapons.” Maybe it’s fitting that some delving is required to reach the ore of the best qualities of this “race apart.”

Del Toro and Jackson don’t have the rights to any of the material in The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, or The History of Middle-earth, which is regrettable because the revenger’s-tale aspect of Thorin Oakenshield’s mission could be deepened and darkened by an allusion or two to the old, old vendetta between Dwarves and dragons. In “The Quest of Erebor” — the pendant to The Hobbit which recontextualizes events through the prism of Gandalf’s grand strategy for saving the West, first published in Unfinished Tales and also available in The Annotated Hobbit (Second Edition, 2002) — wizard admonishes dwarf-grandee as follows: “Smaug does not lie on his costly bed without dreams, Thorin Oakenshield. He dreams of Dwarves! You may be sure that he explores his hall day by day, night by night, until he is sure that no faintest air of a dwarf is near, before he goes to his sleep: his half-sleep, prick-eared for the sound of — dwarf-feet.” But a case can be made that the scaly folk and the longbeards have been figuring in each other’s nightmares since the Battle of Unnumbered Tears in the First Age:

For the Naugrim [Dwarves] withstood fire more hardily than either Elves or Men, and it was their custom moreover to wear great masks in battle hideous to look upon; and those stood them in good stead against the dragons. And but for them Glaurung and his brood would have withered all that was left of the Noldor. But the Naugrim made a circle about him when he assailed them, and even his mighty armour was not full proof against the blows of their great axes; and when in his rage Glaurung turned and struck down Azaghâl, lord of Belegost, and crawled over him, with his last stroke Azaghâl drove a knife into his belly, and so wounded him that he fled the field, and the beasts of Angband in dismay followed after him. Then the dwarves raised up the body of Azaghâl and bore it away; and with slow steps they walked behind singing a dirge in deep voices, as it were a funeral pomp in their country, and gave no heed more to their foes; and none dared to stay them.

(I’m not aware of any evidence that those First Age war-masks survive into the Third Age, but they would make a killer visual for the Battle of Five Armies) But even without Silmarillion-gleanings, the filmmakers enjoy a wealth of back-story in the form of what Gandalf, in “The Quest of Erebor” styles “feuds and disasters on the far frontiers more than two hundred years ago.” Thorin is the heir to those disasters, and del Toro recently said “To me a lot is hanging in the narrative in the relationship between Bilbo and Thorin — obviously because out of the Dwarf group the transformation that Thorin goes through, and the way Bilbo’s character reaffirms itself in light of greed and the desire of ownership that Thorin experiences once they find the treasure trove. . .” My own favorite word-portrait of Thorin can be found not in The Hobbit but the portion of the aforementioned “Quest of Erebor” that Tolkien did squeeze into the ROTK Appendices:

The embers in the heart of Thorin grew hot again, as he brooded on the wrongs of his House and of the vengeance upon the Dragon that was bequeathed to him. He thought of weapons and armies and alliances, as his great hammer rang in his forge; but the armies were dispersed and the alliances broken and the axes of his people were few; and a great anger without hope burned him, as he smote the red iron on the anvil.

He is both smiter and smitten, both a king in exile (from the Smaug-usurped Lonely Mountain) and an anger-heated piece of metal upon which the blows of a great hammer have fallen. A very accomplished (theater-trained?) actor, as well as someone better able than was the long-suffering Rhys-Davies to withstand the facial excruciation of “dwarf-ifying” prosthetics, is required for this role; by the end, the audience should reel as the character addresses Bilbo as “child of the kindly West,” informs him that he “[goes] now to the halls of waiting, to sit beside [his] fathers until the world is redeemed,” and ruefully realizes how Smaug-like he himself became as soon as the dragon-sickness went to work on him: “If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.”

Here’s hoping del Toro and screenwriters Jackson, Boyens, and Fran Walsh manage to convey that Thorin & his followers, whom del Toro has jestingly likened to the Dirty Dozen and the Magnificent Seven, are triple exiles, first from Moria, then from the Grey Mountains of the far north from which they were driven by dragons including a “cold drake,” and lastly from the Lonely Mountain, now the seat of Smaug the Magnificent. “Durin’s Folk,” Appendix III in ROTK, tells us “the Dwarves delved deep at that time, seeking beneath Barazinbar for mithril, the metal beyond price that was becoming yearly ever harder to win. Thus they roused from sleep a thing of terror that, flying from Thangorodrim, had lain hidden at the foundations of the earth since the coming of the Host of the west; a Balrog of Morgoth.” (A footnote that’s always fascinated me suggests “released from prison” as an alternative to “roused from sleep,” speculating that the demonic being was already stirring thanks to “the malice of Sauron”

The Dwarves’ memories of their grievances are longer than their beards, and their tribulations mark them like welts. The more I think about it the more I conclude that what’s needed to do even fast-paced justice to the long and troublous history of Thorin’s kind is a prologue like the one that gave the screenwriters fits but ultimately did its job so well in The Fellowship of the Ring; del Toro saw fit to begin Hellboy II this past summer with something similar. Six, seven, or eight minutes briefing the uninitiated on the abandonment of Moria to the Balrog and the ensuing War of the Dwarves and the Orcs, which as related in the “Durin’s Folk” Appendix was the showcase, in the years before the publication of The Silmarillion and the “Wanderings of Húrin” fragment, for Tolkien’s matchless gift for saga-stuff. Such a prologue might be miserly with names — Gil-galad and Elendil aren’t identified during the Dagorlad sequence in Fellowship — but we would still glimpse the ill-advised coming of the rightful lord Thrór, “a little crazed perhaps with age and misfortune and long brooding on the splendour of Moria in his forefathers’ days,” to the wrested-away kingdom, prideful as “an heir that returns.” The contemptuous separate expulsions of his head and body “many days” after his entry, to the accompaniment of “orc-laughter in the shadows,” and the jeers of Azog, who has gone so far as to brand Thrór’s brow with his own name in dwarf-runes: “I wrote it! I killed him! I am the master!” Insult on the iron-shod heels of injury as loyal fellow wayfarer Nàr is tossed a pittance-bag, “few coins of small value” as a “fee” to deliver a message to the other “beggar-beards.” His flight as the Orcs emerge, “hacking the body and flinging the pieces to the black crows.” The furious clangor of hammer on anvil in every dwarrowdelf as the news spreads, the muster of a last great host, the “death and cruel deeds by dark and by light” as the maddened weapon-forgers turned weapon-wielders hunt down Azog. The climactic Battle of Azanulbizar, “at the memory of which the Orcs still shudder and the Dwarves weep.” The slaying of Nàin by Azog and of Azog by Dàin Ironfoot, and the sinister hint of what the new hero senses or surmises, there on the very doorstep of Moria: “. . .hardy and full of wrath as he was, it is said that when he came down from the gate he looked grey in the face, as one who has felt great fear.” The insult answered at last: “They took the head of Azog, and thrust into its mouth, the purse of small money, and then they set it on a stake.” The chastened mood of the survivors: “If this is victory, then our hands are too small to hold it.”

In the actual Hobbit Tolkien refers to a goblin-grudge “against Thorin’s people, because of the war which you have heard mentioned, but which does not come into this tale.” But the prologue we’ve just outlined, like the loss of the Lonely Mountain to Smaug, would inform the rest of the first of the two new movies, moments like Bard’s grim assessment of the advancing dwarf-host: “They do not understand war above ground, whatever they may know of battle in the mines.” Or Gandalf’s words to Ironfoot: “Bolg of the North is coming, O Dàin, whose father you slew in Moria. Behold! The bats are above his army like a sea of locusts. They ride upon wolves and Wargs are in their train!” (Evidently the War of the Dwarves and Orcs did creep into Tolkien’s tale a bit) Swiftly establishing the brutal mystique of Azog as a fearsome Dwarf-bane in a prologue will lend blunt force trauma to the appearance of his payback-lusting son Bolg just before the outbreak of general hostilities.

As for Smaug, he must bestride the earth like a saurian colossus, even posthumously; the leadup to the Battle of the Five Armies is really a succession struggle, a dispute over who will be the next dragon king. Listen, as Thorin fails to do, to the warning delivered by Roäc son of Carc (the Raven Anti-Defamation League-endorsed counterweight to the cawing “spawn of perdition” that torments Conan in The Hour of the Dragon):

“The news of the death of the guardian has already gone far and wide, and the legend of the wealth of Thror has not lost in the telling during many years; many are eager for a share of the spoil. Already a host of the elves is on the way, and carrion birds are with them hoping for battle and slaughter. By the lake men murmur that their sorrows are due to the dwarves; for they are homeless and many have died, and Smaug has destroyed their town. They too think to find amends from your treasure, whether you are alive or dead. “

Del Toro continues to talk not just a good but the best of all possible games when it comes to Smaug; he’s recently extolled draconitas in general as “Fear and awe inscribed in our very genes. Dragon and man tangled in the dreams of an unending spiral of X’s and Y’s,” creatures “equally feared and admired, cherished and longed for as a lost creature of Eden.” And he’s well aware that Smaug’s surroundings are an externalization of his essence: “Understanding that designing Smaug you have to design Lonely Mountains, not Lonely Mountains, inside and out, because it will tell you who he is in a way that — to use a majority example — in the way that the first time you go inside: Tony Montana in a white suit walking in a marble palace — you know exactly who he is — the gold chains. . .”

Smaug as Tony Montana is a diverting conceit; since reading that GDT interview earlier this week I’ve been unable to stop imagining a red-gold dragon lolling on his hoard and inviting Bilbo to say hello to his little friend or explaining that “In this country, first you get the money, then you get the power, then you get the woman,” all in Al Pacino’s version of a Marielito accent. More serious guidance for voicing Smaug is available in this passage from Tom Shippey’s The Road to Middle-earth :

He speaks in fact with the characteristic aggressive politeness of the British upper class, in which irritation and authority are in direct proportion to apparent deference or uncertainty. ‘You have nice manners for a thief and a liar’ are his opening words to Bilbo (their degree of irony unclear). ‘You seem familiar with my name, but I don’t seem to remember smelling you before. Who are you and where do you come from, may I ask?’ He might be a testy colonel approached by a stranger in a railway carriage; why has Bilbo not been introduced? At the same time the ‘bestial life’ of the worm keeps intruding, as he remarks on Bilbo’s smell and boasts parenthetically ‘I know the smell (and taste) of dwarf — none better’, or when he rolls over, ‘absurdly pleased’ like a clumsy spaniel, to show the hobbit his armoured belly.

Is it so wrong to associate the ruling class of any era with reptilian speech patterns? (Well, perhaps that’s unfair to reptiles, who haven’t really been running things since the Dragon Kings of Elder Hyperborea) Were Ian McKellen not so indelibly associated with another character, the voice he uses in his 1995 film Richard III, which relocates Shakespeare’s schemer –now half Duke of Windsor, half Oswald Mosley — to an increasingly Blackshirted British Thirties, would be purrfect for Smaug.

In any event, del Toro is righter-than-right to zero in on the design of the wyrm’s digs, which should be as eloquent as a drug-lord’s luxury lair or Blofeld’s hollow volcano in You Only Live Twice. Tolkien, like Robert E. Howard, was extraordinarily attentive to symbolic lighting effects in treasure-scenes:

Beneath him, under all his limbs and his huge coiled tail, and about him on all sides stretching away across the unseen floors, lay countless piles of precious things, gold wrought and unwrought, gems and jewels, and silver red-stained in the ruddy light.

Del Toro and his cinematographer should highlight that description, and also this one of the elf-combatants in the Battle of Five Armies: “Their hatred for the goblins is cold and bitter. Their spears and swords shone in the gloom with a gleam of chill flame, so deadly was the wrath of the hands that held them.” Christopher Lee’s Saruman touched upon the atrocious origins of the Orcs in The Fellowship of the Ring, and little would be so conducive to a higher, deeper, darker Hobbit than a screenplay that found a way to reinforce the “We have met the enemy and he is us” underpinnings of the Elves’ “cold and bitter” hatred:

All those of the Quendi [Elves] who came into the hands of Melkor, ere Utumno was broken, were put there in prison, and by slow arts of cruelty were corrupted and enslaved, and thus did Melkor breed the hideous race of the Orcs in envy and mockery of the Elves, of whom they were afterwards the bitterest foes.

I get a kick out of Scott Oden’s “weird fascination with Orcs,” but for me to reconfigure them as an unlovely-but-arguably-racially-profiled warrior-race, unrestricted free agents looking for a destiny of their own is to risk losing the plot. It’s precisely the fact that they were gengineered in the hells beneath the halls of a Dark Lord — “And deep in their dark hearts the Orcs loathed the Master whom they served in fear, the maker only of their misery” — the tension between slavery and sentience that characters like Gorbag and Shagrat evince, that renders them so compelling.

That having been said, the northron-orcs of The Hobbit do differ from Sauron’s conscripts; as John Rateliff writes “The goblins are presented for the first time as something more than swordfodder, having their own (admittedly wicked) culture and civilization, complete with poetry, commerce, an apparently thriving slave-labor industry, a hierarchical society from the Great Goblin on top down through the warriors to the slaves, and xenophobia.” In view of del Toro’s interest in an archaic arms race as part of the mythology of Hellboy II, he might be intrigued by Tolkien’s notion that “It is not unlikely that [goblins] invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once, for wheels and engines and explosions always delighted them.” William Manchester’s classic The Arms of Krupp never mentioned that the dynasty had goblin-blood in its veins. . .

This whole post isn’t just a selfish attempt to rip a beloved book out of small, innocent grasps. Tolkien himself left the start of a trail of adaptation-crumbs for del Toro and Jackson to follow. In 1960 he embarked upon a retrofitting of The Hobbit to render the “enchanting prelude” a little bit less enchanting and a little bit more of a prelude. The rewritten chapters are available in The Return to Bag End, where they provoke a magical piece of what-iffery from John Rateliff:

We cannot know what else Tolkien would have added to the story, had the 1960 Hobbit or Fifth Phase continued beyond this point. Bilbo could not have met Arwen at Rivendell, for we know she was at that time in the middle of a decades-long visit to her grandparents, Galadriel and Celeborn, in Lórien. But did Bilbo’s lifelong friendship with Aragorn (then a ten-year-old living in Rivendell with his mother and being raised by Elrond) begin during his visit there, either on the outgoing or the return trip? Did Legolas Greenleaf fight in the Battle of Five Armies? Would more light have been cast upon the storm-giants of the Misty Mountains, or the source of Beorn’s enchantment, or would we have learned a little more about the elusive Radagast? Would the Spiders of Mirkwood have been made more horrific, àla Shelob, and the wood-elves absolved of all blame in the treatment of the dwarves? Would Balin’s visit in the Epilogue include some mention of his plans for Moria? And most importantly, would the Ring have been presented in more sinister terms throughout, with hints of his corruptive influence even on one such as Bilbo?

After such knowledge, what forgiveness? asks T. S. Eliot in “Gerontion.” After the knowledge that millions have acquired by reading The Lord of the Rings, and tens of millions have acquired by watching the Peter Jackson films we can neither “forgive” the Ring nor travel “back in time” to perceive it as a relatively innocuous, invisibility-conferring trinket. Similarly, after Gandalf the White and even Gandalf the Grey it will be quite difficult to retrench to the more limited and rather part-time wizard of The Hobbit. Which is why, ensnaggled in a thicket of litigation though the Tolkien Estate and the corporations financing the new movies may be, I burn for a side-deal to be cut allowing access to “The Quest of Erebor.” That material’s entrée to Gandalf’s oft-veiled Valinorean perspective would redouble higher, deeper, and darker: “. . .I used in my waking mind only such means as were allowed to me, doing what lay to my hand according to such reasons as I had. But what I knew in my heart, or knew before I stepped on these grey shores: that is another matter. Olórin I was in the West that is forgotten, and only to those who are there shall I speak more openly.”

But what he does say in “The Quest” is strikingly open, as when he confides that his reasoning at that time was “that of a captain, a member of a Council of War,” one preoccupied with Sauron’s ever-longer reach: “Smaug he might use with terrible effect.” So too is Gandalf’s take on Thorin revealed to have been that “He was involved, as I saw only too well, in the net of Sauron’s designs, a dark strategy beyond his powers, and beyond his grasp.”

John Rateliff is less fond of “the Quest” than I am: “Fascinating though it is, ‘The Quest of Erebor’ does set one unfortunate precedent: it diminishes Bilbo in the reader’s eyes, casting him very much as a silly fellow puffing and bobbing on the mat. Gandalf, after describing Bilbo as ‘rather greedy and fat’, says the hobbit ‘made a complete fool of himself’ and ‘did not realize. . .how fatuous the Dwarves thought him. . .Thorin was much more . . .contemptuous than he perceived.'” And yet Gandalf also deems Bilbo “neat-handed and clever, though shrewd, and far from rash. And I think he has courage. Great courage, I guess, according to the ways of his people.” It seems to me that this high praise from the Middle-earth sojourner from whom one would most desire praise balances out his more exasperated assessments. “The Quest” is always going to be read as an afterthought, a postprandial morsel, and for anyone/everyone who’s read The Hobbit and LOTR first, Bilbo’s stature is impervious to shrinkage. Far from talking down to young readers, the second half of The Hobbit raises them up to a height where the perils and rewards are a dizzying departure and to keep up with Bilbo, they must grow up like he does. The recollection of that process makes the Gandalfian snark in “The Quest” enjoyable rather than belittling (Part of the cumulative power of Tolkien’s characterization of his wizard is the way the stress of Gandalf’s responsibilities as “the Enemy of Sauron” unleashes itself every so often in flashes of asperity, like heat lightning: “This dwarvish conceit that no one can have or make anything ‘of value’ save themselves, and that all fine things in other hands must have been got, if not stolen, from the Dwarves at some time, was more than I could stand at that moment.”

In effect a continuation of “The Quest of Erebor,” the 1960 Hobbit rewrite didn’t get all that far; Tolkien tested the “new” chapters on a friend, and as Rateliff tells it

We do not know this person’s identity, but apparently her response was something along the lines of ‘this is wonderful, but it’s not The Hobbit.’ She must have been someone whose judgment Tolkien respected, for he abandoned the work and decided to let The Hobbit retain its own autonomy and voice rather than completely incorporate it into The Lord of the Rings as a lesser ‘prelude’ to the greater work.

My own inclination is to reply across the decades to the unidentified test reader that “This is wonderful, and it’s The Hobbit as it might well have been.” And I would quibble with Mr. Rateliff’s word “lesser”; yes, a prelude can labor under something of a disadvantage in that it comes first, but there is nothing lesser about Smaug the Magnificent and the Battle of Five Armies. Witness this Tolkien passage: “Messengers had passed to and fro between all their cities, colonies and strongholds; for they resolved now to win the dominion of the north. Tidings they gathered in secret ways; and in all the mountains there was a forging and an arming.” The more dangerous the ancient northern world into which Gandalf coaxes Bilbo is shown to be, the more impressive his gradual adjustment — while preserving his defining decency — will be.

In a medium-hopping sort of way, the Hobbit films represent a second chance for Tolkien’s discarded 1960/Fifth Phase version. Del Toro has said ” The first film will stand on its own, and the second will be a transition and fusion with Peter’s world. I plan to change and expand the visuals from Peter’s, and I know the world can be portrayed in a different way. Different is better for the first one,” but in other interviews he has emphasized the seamless incorporation of The Hobbit into the greater work as a desideratum, with an ultimate goal of a five-film, two-director whole. Can the earlier adventure “retain its own autonomy and voice” as part of such a grand continuum? The worry for many Hobbit-lovers is that charm will be sacrificed on the altar of consistency; characters and events, particularly in the pre-Lonely Mountain chapters, are going to be forced to put away childish things even as they were in the process Tolkien began in 1960. But for me results that approximate “The Quest for Erebor” or those redone Fifth Phase chapters will be quite livable with, and livable-for. A stage suitable for the great Smaug, a Thorin who rises to the occasion, and then falls, and then rises again, a Volstaggian Bombur, an Elvenking-thesp who can make music with lines like “Long will I tarry, ere I begin this war for gold,” or “You are more worthy to wear the armour of elf-princes than many that have looked more comely in it,” the latter of which always reminds me of Amalric’s double-take in “Black Colossus”: “By my finger bones, Conan! I have seen kings who wore their harness less regally than you!” But also a stage spotlighting a casting coup who performs much the same miracle Robert De Niro pulled off in The Godfather Part II: uncannily presaging the older Bilbo without simply doing an Ian Holm impersonation.

As we have already seen, in 1965 Tolkien adduced “glimpses that had arisen, unbidden, of things higher or deeper or darker than [The Hobbit‘s] surface”; if new glimpses arise, only this time bidden, in the 2011 and 2012 movies, so be it, provided they are indeed satisfyingly higher, deeper, and darker.