“I’ll Kill the Mama-Mfuka”: The Trail of Bohu in 2009

Thursday, March 5, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

He saw Naama, its dark battlements thrusting against the sky of Land’s End. He saw the Erriten bathing in the emerald of mchawi. He saw the cities of the East Coast crumbling in blood-smeared ruin. He saw a cloud of darkness crawling inexorably northward…thousands upon thousands of armed men, and others who were not human at all, a cloud thicker than a thousand swarms of locusts and a thousand times more destructive. He saw the turrets of Gondur torn apart, stone by stone, and the stelae flung down to shatter in the streets. He saw his people dragged screaming to altars to be sacrificed to the Demon Gods. He saw the Erriten towering gigantic and triumphant, dominating all of Nyumbani. He saw the seed the Mashataan intended to sow to replace the children of the Cloud Striders…

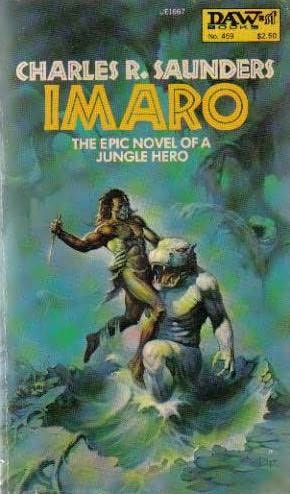

Charles R. Saunders never left Imaro, nor did Imaro leave him; instead, the possibility of further publication left both of them for two decades after The Trail of Bohu (1985). The last of the three Saunders heroic fantasies from DAW Books in the Eighties, Bohu is its creator’s favorite because, as he informs us in an Author’s Note at the end of the revised-and-self-published 2009 edition, “it was the first Imaro novel that I wrote from scratch…Completing a novel that did not include previously published material was a major milestone in my development as a writer.” Those of us who pounced upon the 1985 version (insofar as its non-sea-to-shining-sea distribution allowed) have also always cherished Bohu for boasting the biggest budget, the most ambitious special effects, and the most on-location filming. Nyumbani grows by leaps and bounds, and the effect is as exhilarating as the opening of “Black Colossus,” wherein Shevatas orients himself in the ruins of Kuthchemes with a tour d’horizon encompassing fabled realms to the southwest, the east, and the north, all of which he knows “as a man knows the streets of his town,” or the scene near the end of The Fellowship of the Ring during which Frodo, his perspective newly panoptic thanks to the Seat of Seeing, in effect watches as the slavering jaws of the world war launched by Sauron close around Middle-earth.

We carry within the wonders we seek without us, Sir Thomas Browne wrote, There is all Africa and her prodigies in us: The Trail of Bohu in particular carries within it a prodigious number of African prodigies, both civilized (the glory that was Kush and the grandeur that was Great Zimbabwe) and barbaric — the trail in question leads past the most notorious killing fields in the history of southern Africa. The novel begins with inclement weather, with weather, in fact, that does not know the meaning of the word clemency. A storm is brewing at the southern end of Nyumbani, and the phrase “end of Nyumbani” applies in more ways than one. As we witness the enormities occurring in the High Chamber of the Erriten of Naama, which herald enormities greater still, the theme of both “The Call of Cthulhu” and “The Shadow Kingdom” swells again, the theme of man as an eviction-inviting squatter in a condemned edifice. In the words of Abadu, a character in David C. Smith’s novel Oron, “Humankind holds its life and its lands but precariously — and perhaps not at all.”

Naama is what Nyumbani has instead of Capetown, the peppercorn tufts of hair of the eldest Erriten Chibenguela are the trademark of a fantasticated Hottentot (the Khoikhoi of Cape Province), and the flat-topped massif on which the lightning-crowned citadel rises is of course Table Mountain, but this site-choice is anything but the way-down-yonder whimsy of de Camp and Carter’s Conan of Aquilonia, in which Yanyoga, the last bastion of the serpent-men to which the stumblebum Thoth-Amon flees, is situated at the southernmost extremity of the Thurian/Hyborian continent. In 2009 it is worth remembering that Saunders wrote The Trail of Bohu in 1983-1984, when the South African townships were burning, the smoke therefrom wafted all the way to American campuses, and the dubious constructiveness of the U. S. policy of constructive engagement was more apparent with each passing week. Apartheid’s ideological and administrative capital was Pretoria, but in the symbolic geography of southern Africa, Capetown is where it all began to go wrong, where the European encroachment came ashore. So there is wit and a withering aptness to the fact that in the symbolic geography of the Imaro saga, Naama is where Nyumbani stops and the dominion of demons begins.

Karl Edward Wagner was ahead of his rather undemanding time in insisting that the best Sword-and-Sorcery can be enjoyed on multiple levels, and where poor old Thongor of Valkarth would need a depth-transplant to be even one-dimensional, Imaro has always been a multi-layered protagonist operating in a multi-tiered world. One of those tiers is thoroughly (but always enjoyably) decolonizing, the counter-projection or super-projection of an African-American writer’s corrective ideas upon his much projected-upon Mother Continent. In his uproarious “City of Madness,” (part of the DAW Imaro but moved to open The Quest for Cush in the 2007 Night Shade edition), Charles Saunders scalpel-handedly subjected that pulp mainstay the Atlantean colony to a mystique-ectomy, and in The Trail of Bohu he Africanizes a plethora of Ophirs and Opars and Opets — all the proposed solutions to a supposed riddle that required, in Basil Davidson’s words, “calling up some more or less mythical people from ‘outside'” — by reclaiming Great Zimbabwe as Nalitali, the capital of an empire in the southern region of the Maguvurunde that joins Cush as a prime mover in the war against Naama. As Henry Louis Gates points out in Wonders of the African World, “Great Zimbabwe’s origins were a metaphor — the central metaphor — for the intelligence of black Africans and their right to govern their own land and nurture their own traditions. What is most ironic is that Europeans located many of their own most far-fetched fantasies in the depths of southern Africa, then argued widely that only non-Africans could have placed them there.” But the irony didn’t stop there; as Saunders prepared the 2009 Bohu, he was forced to deal with the fact that the once-magical place name Zimbabwe was now synonymous with criminality and a personality cult threatening like some mutant tumor to devour an entire nation:

In 1983, the time when I wrote the first version of Bohu, Zimbabwe – the nation formerly known as Southern Rhodesia and Rhodesia – had been independent for only a few years. The name still evoked mystery and intrigue because of its association with stone ruins and hidden history.

That exotic association is gone now. Zimbabwe is embroiled in the type of post-independence conflict that has unfolded throughout the African continent over the past several decades.

Thus, in the imaginary continent of Nyumbani, Zimbabwe has become Amanyani, a name rooted even deeper in legend.

The Imaro series is dominated not only by its hero but by give-and-take between names rooted in legend and associations rooted in reality. History took “Slaves” away from Saunders, left him so concerned about what might be misconstrued as the reduction of genocide to violent entertainment that he excised the novella (incorporated in the first Imaro novel back in 1981) from the 2006 Night Shade version. For background, read his February 19 “My Rwanda Quandary” post at the Drums of Nyumbani blog, and the February 24 reply by TC’s new recruit Deuce Richardson, also at the Saunders website (Forum page).

Nyumbani has entailed choices that it is difficult to imagine, say, Fritz Leiber grappling with when creating the peoples of Nehwon; I’m aware of no evidence that Mongols were ever fazed by the Mingols of the Fafhrd and Mouser stories. And yet it was Leiber, no prisoner of ideology or identity politics, who contended in “Fafhrd and Me” that “Fantasy must be fertilized — yes, watered and manured — from the real world.” Blood, sweat, tears, even the seepage from an incurable wound like Imaro’s — all can be essential nutrients in the processes Leiber recommends, and I can assure anyone inclined to recoil from an apparent politicizing or polemicizing of what Lin Carter and L. Sprague de Camp would have us believe is the most escapist of subgenres that Nyumbani is strengthened rather than weakened by being so clearly adjacent to and contingent upon the history we know, or think we know. We can see a similar technique in David Anthony Durham‘s Acacia: The War with the Mein (2007), a story not only of royal siblings with a suggestion of the Pevensies in the Narnia books but of what an institutionalized-and-intercontinental slave trade does to the enslavers as well as the enslaved.

When interviewed by Morgan Holmes for the latter’s zine Forgotten Ages #18 (REHupa Mailing #136) Saunders emphasized that he “was studying African history, culture and mythology long before Afrocentricity became a part of the landscape.” The Imaro stories are fascinatingly Africa-centered without being tendentiously Afrocentric, and Cush, ruled by the Kandisa and uplifted by the Cloud Striders, is at the center of that centeredness. After an early, skid-greasing atrocity in Bohu Cushite civilization and Imaro’s barbarism confront each other, their instinctive antagonism intensified by the fact that civilization has previously coaxed barbarism into a gilded cage, a cage through the bars of which Imaro’s enemies have just stabbed at him. “A wolf was no less a wolf because a whim of chance caused him to run with the watch-dogs,” muses Balthus in “Beyond the Black River”; “Bloodshed and violence and savagery were the natural elements of the life Conan knew; he could not, and would never, understand the little things that are so dear to civilized men and women.” Imaro has made an effort for five years to understand the little things that mean so much to his wife Tanisha, his only real friend Pomphis, and the Kandisa, but that hard-won understanding is now lost, inundated by Howardian bloodshed and violence and savagery: “All these rains, I waited. I made weapons I did not use, ” Imaro rages, “I played at games. I was like Ngatun in a cage. All that time, you said I must wait before striking at the Naamans.”

This confrontation takes place in the Sakkhar, the Cushite House of the Dead, a backdrop against which the African and the American elements of Saunders’ heroic fantasy stand out in sharp relief. Here I can’t resist revealing that the 2009 Bohu includes a gloriously recidivist callback to the blaxploitation context in which the Imaro series took shape back in the Seventies; challenged as to what he can hope to achieve against a new foe terrorizing much of Nyumbani’s east coast, Imaro answers “I’ll kill the mama-mfuka.” Would that Isaac Hayes were still with us to do justice to that line for an audiobook, or punctuate it with some basso-funkily-profondo on the soundtrack for a movie adaptation.

African reverence for the accumulated wisdom of the ancestors, a culture in which the departed do not depart but linger in an advisory capacity, conflicts with the American imperative to be out from under the dead weight of the past, a yearning to breathe freely oppressed by the necrophile or necromantic aspect of the Sakkhar: “Blindfolded as he was, Imaro saw nothing of the many tiers of niches that contained the previous rulers of Cush. But he did smell an acrid residue of the natron and bitumen used to preserve the flesh of the royal cadavers. The odor matched the bitterness of his thoughts.” Indeed, something about the whole setup stinks, despite the preservatives. A few of us have detected “an acrid residue” ever since The Quest for Cush revealed that the Cushite savior Tiharqua was a whited sepulchre, a Redeemer who thought nothing of damning an entire people in perpetuity for having fought on the wrong side in the Mizungu War. Cush is the counterweight to Naama in the seesaw balance of power known as khephet, but Saunders is also careful to place these Chosen of the Cloud Striders on a different set of scales where they are found wanting. Imaro has always been both human wound and human weapon; the Cushites are anxious not to cure the wound but to deploy the weapon.

One chapter of Bohu whisks us to “mountain-girt Gondur,” seat of the Amhar Throne of the Negus Negusti, Axum’s King of Kings, a setting redolent of the “mighty past” W. E. B. DuBois discerned in “the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and Egypt the Sphinx.” Axum and the mightier realm where Imaro has more or less settled at the novel’ start coexist no more harmoniously than Nemedia and Aquilonia:

For the feud between Axum and Cush was an ancient one, dating back thousands of rains to a day when a golden-eyed shaman decided to worship Atun the sun while his dark-eyed brother chose to honor Alamak the moon. In the rains that followed, the Cushites became the People of Atun, and the Axumites the People of Alamak.

As decades stretched into centuries, Cush grew mighty and prospered, but Axum never shared the bounty of its neighbor. The People of Alamak retreated into their mountain fastness, eking out a grudging subsistence from a harsh, barren land. At Gondur. they built a city of frowning turrets and votary stelae that reached toward the moon and its attendant stars.

Alamak and Atun cannot shine in the same sky…

Every child of Axum learned that proverb from birth. The history of Cush and Axum was one of warfare, interrupted by intermittent periods of peace. Only once had Cush and Axum battled on the same side: a thousand rains ago, for the purpose of ridding Nyumbani of the Mizungus of Atlan.

Other chapters draw upon horrors less rawly recent than the Rwandan genocide that ruled out republication of “Slaves of the Giant-King” for Saunders. In one of the novel’s “Interludes,” we learn that the Erriten have opened a new front in their war on the peoples of Nyumbani: Nongkwaze, a girl blessed, or cursed, with “unkansi,” clairvoyance. “Because of what Nongkwaze saw in the pool,” we are told, “War-drums were muttering throughout the Abamba Highlands.” What she glimpses is what it is intended that she should glimpse:

She saw cattle being slaughtered by the thousands, and the pool turned dark with their blood, and inside her head she could hear their bellows of betrayal and agony… She saw millet fields being set afire, and the flames flared brighter than the sun, and the smoke blotted out the sky…

She saw emaciated men, women, and children laboring like ants to dig out huge pits larger than whole villages…

She saw the sky crack open like a broken groundnut, and the light poured out of the crack like water, and from the light emerged the titanic figures of gods, each one driving a herd of cattle the size of elephants…

She saw the gods pour a never-ending supply of grain into the pits dug by starving people…She saw all the tribes of the Abamba Highlands falling before the spears of the Tsubi, who had eaten the grain and cattle of the gods, and had become like gods themselves…

Her visions are replaced by “a flat black shadow” on the pool’s surface, a shadow that provides “no reflection of moon or stars.” But then genuine illumination has no business here, as the seeress rushes to repeat shadow-taught words to her people “before they slid down her throat and choked her.” Behind her there is laughter for about the space of a sentence, the laughter of Bohu, the catastrophe-catalyst the Mashataan have loosed upon Nyumbani.

The credulous Tsubi are stand-ins for the historical Xhosa. Already traumatized by defeat in no fewer than nine Cape Frontier Wars against the British Empire and facing what Ian J. Knight in his Warrior Chiefs of Southern Africa (1994) terms “deliberate and systematic breaking,” this people harkened to garbled reports of the Crimean War and having fought as long and as hard as was humanly possible, allowed themselves to dream of what might be inhumanly possible. Saunders’ Nongkwaze doppelgängers the Xhosa Nonqawuse: a young niece of the prophet Mhalakaza who in April or May of 1856 having shooed the birds from the kraal’s cornfields, was cooling off in a pool when two strangers appeared. As Noel Mostert tells it in Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa’s Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People (1992):

The names they gave were of men long dead. They instructed the girls to deliver their respects to the kraal and to advise everyone that a great resurrection was about to occur, but to ensure it the people were to kill all living cattle. There was to be no sowing and cultivation. The storage bins were to be emptied of corn and their contents scattered. All witchcraft had to be abandoned. Once these instructions had been complied with, the girls were told preparations had to be made for the new world that would emerge through the resurrection.

The American reader might be reminded of the Ghost Dance of the Plains Indians — when people are about to lose their land, their culture, and their freedom they often lose their skepticism first. Mostert’s recreation of this volitional famine has haunted me ever since I first read Frontiers:

It would be hard to convey the terrible emotional turmoil that the killing imposed. There were sufficient doubts among even the most energetic killers of cattle to create great mental disturbance. There must have been intense regret as one looked at a favorite ox, the winner perhaps of many splendid races, at beloved milking cows, and painful alarm at the sight of the whole herd grazing about the kraal, the wealth of a man, the riches of a chiefdom, the lobala of the brides, and above all, the hallowed animals in the funeral kraal of a deceased chief — meant to die a natural death — all to be sacrificed in faith. It must have been particularly terrifying to contemplate at that marvelous hour, milking time, when the boys went out to their allotted cows, when the swift, purple dusk flickered with numerous fires and the singing that accom¬panied the hour grew steadily more harmonious and cheerful, anticipatory, as all awaited the evening meal; and then knowing that, once carried through to the end there would be an evening when no cows came home, no one went to milk, the milk sacks were empty, and all would be waiting, silent, hungry, songless.

Nor is Bohu. a glutton for the punishment of others, content to rely upon famine and fanaticism. Charles Saunders repeats the phrase “Mfecane… the crushing” five times during the two-page Interlude between Chapters Sixteen and Seventeen of this novel, as if invoking an evil spirit, and the intervening paragraphs are themselves an invocation of the most murderous protagonist in a southern African tragedy:

To the east, a powerful nkosi or chieftain had risen like an awakening giant. When the giant stood, all others trembled in his shadow. Shingane was the nkosi‘s name — Shingane the Mad, Shingane the Terrible, Shingane the Great Elephant.

With the swiftness of fire spreading through dry grass., Shingane had claimed the plume of nkosi of the Mtatwa. an insignificant eastern tribe. He taught the Mtatwa new methods of warfare, and showed them new depths of cruelty. Soon the Mtatwa warriors worshipped Shingane as a god. The Mtatwa women feared him as though he were a devil. But they dared not voice their misgivings, lest they be named as witches by Shingane’s isangoma, or witch-smellers.

Ruthlessly and efficiently, the Mtatwa conquered their neighbors. The young men of the defeated tribes were pressed into service in Shingane’s impis — regiments of warriors. The young women were taken as wives to replace Mtatwa women named witches by the isangoma. All others were slaughtered, and their cattle stolen to augment Shingane’s immense herd.

Shingane’s empire of blood spread through the eastern reaches of the highlands while the Tsubis’ terror dominated the south and west. The highlands were wracked by turmoil, and no tribe trusted its neighbor.

The voice whispering “words of conquest and grandeur and blood” in the attentive ear of Shingane is Bohu’s, and that ear is of course modeled on that of Shaka Zulu (“Shingane” — a conflation of Shaka and Shaka’s younger brother, assassin, and successor Dingane?). The Mtetwa are the Zulus in all but name, and the Mfecane remains the Mfecane. All of the gory details (and details have seldom been so gory) save for Bohu himself are borrowed from the Shakan epic, aspects of which also underlie Pagan in David Gemmel’s The King Beyond the Gate (1985) and Manatassi in Wilbur Smith’s The Sunbird (1973).

The Zulus are not only a warrior people but a people much warred-over by social scientists. Unlike, say, the reinvention of the Vikings by contrarian-historians as misunderstood goodwill ambassadors, ale-fellow-well-met merchant-mariners, interpretations of Zulu-ness in post-apartheid South Africa have often been politically pointed, and poisoned. In creating, or permitting Bohu to create, Shingane, Charles Saunders dipped into the same crimson inkwell as Nathaniel Isaacs, who survived his sojourn at the despot’s court and ogre-fied him in Travels and Adventure in Eastern Africa as “a monster, a compound of vice and ferocity without one virtue to redeem his name from the infamy to which history will consign it. ” H. Rider Haggard’s Zulu warlord in Nada the Lily (1892) “slaughtered more than a million human beings” on the way to an empire in which the sun itself “set redly, flooding the land with blood” so that “all the blood that Chaka had shed flowed about the land Chaka ruled.” Some more recent historians have sought to scour this abbatoir, to argue that Shaka was not only assassinated by his own brothers but character-assassinated by colonial propagandists.

Shingane is Nyumbani’s Shaka-figure, but Shakan elements possibly found their way into the series as early as Imaro, in which Saunders may have been inspired by the anecdotal sources that Stephen Taylor cites in his Shaka’s Children (1992): “Shaka, an mlandwana or illegitimate child, was bullied and teased. It is easy to imagine childhood, in the pastoral, enfolding and prosperous society of the southern Africa savannah, as an Elysium. For Shaka, it was wretched. Boys were responsible for herding and milking; Shaka was put in charge of a cow which was notorious for goring and almost impossible to milk…His youthful fury at the world started to find expression in rebellion. He antagonized the relatives with whom he was living and quarreled with his peers. Powerfully built, he could assert himself painfully…”

Ian J. Knight agrees that “By all accounts. Shaka had a miserable childhood”; the man of destiny “grew up aloof, lonely and quarrelsome.” Being plagued by one’s peers was an incentive to become peerless: “Once, at mealtime, they had forced him to hold out his cupped hands, into which they poured scalding hot curds. Even at his age. Shaka was not one to take such treatment lightly, and his fearsome temper eventually got the better of him, and led to his expulsion from the clan once more. ” Very similar to lmaro’s deformative years, and the upshot was much the same: Taylor quotes one of the first isibongos (praise songs) lauding Shaka as “the stabber who surpasses all others,” and comments that “tales of his early career, of mortal struggles with wild animals and men possessed by demons, are in the classical tradition of myth and legend.” He also stresses how large the people Shaka welded into an abuse-avenging weapon came to loom in the British imagination:

In the imperial gallery of ethnic prototypes — from the dashing Pathans and swaggering Sikhs on the North-West Frontier, to their mettlesome counterparts in the antipodes, the Maoris and Fijians of the south Pacific — the warrior was held to have reached his apotheosis in the people known variously as Zooloos, Zoolahs, or Zulus. The popular image of this figure was the stuff of nightmares: a regimented and celibate man-killer, without fear or pity, he was said to roam southern Africa in swarms akin to the wild creatures there. He went naked but for a bare covering of skins and feathers, carrying a cow-hide shield the size of an ordinary mortal and a short stabbing spear that was as effective in his hands as the gladius of the Roman legions. He lived for conquest and plunder. In short, he represented the elemental brute in Africa that Europeans had decided it was their duty to tame.

T. H. White, whose Celtophobia was a sepsis in the nobility of The Once and Future King, scared himself silly in a 1936 novel called Farewell Victoria. White’s Zulus are “an army of ants, automatically fearless and unforgiving…” Alternately, taking them on is “like fighting a different and incalculable species — a species like the termites. ” Having anticipated the “bug hunt” vocabulary of the wartime Pacific (and postwar, Starship Troopers-style science fiction) he continues to grope frantically for the right words to describe Zulu wrongness: “The Zulus came on, blood-lusting, incomprehensible. These death-dealing stabbers were black, were impossible. Their bodies smelt strangely; their expressions were inhuman; their cries were in a foreign tongue, were those of beasts and cattle.”

But whenever savagery is imputed to a tribe or ethnic group it is only a matter of time before noble savagery is imputed as well; if the “metropolitan” imperial mindset isn’t trying to Romanize the people in question, it romanticizes them. The martial magnificence of the Zulus proved imperishable even as the warriors perished by the thousands at Isandlwana, where they won, and Ulundi, where they lost. Stephen Taylor: “Imperial soldiers recognized a noble foe, savage or not, and the Zulu way of giving battle — charging across open ground in massed ranks, armed with assegai and cowhide shields. in the face of withering fire — was the very stuff of raw courage. With their splendid appearance, burnished black bodies draped in animal skins and ostrich plumes, they were, as Jan Morris has noted, the most spectacular of all the theatrical enemies the British Empire felt itself obliged to fight. On the mounds of Zulu dead, some eight thousand of them, there arose a new paradigm for the warrior nation.”

And that new paradigm was to H. Rider Haggard Haggard what the Mohicans were to James Fenimore Cooper, the difference being that, as Wendy R. Katz points out in Rider Haggard and the Fiction of Empire: A Critical Study of British Imperial Fiction (1987) there existed a real live Zulu culture into the depths of which Haggard at least waded as a colonial official. He was far out in front of the Colonel Blimps and Commander McBraggs of his time in realizing the existence of such depths, maintaining that “in all the essential qualities of mind and body [the Zulus] very much resemble white men, with the exception that they are, as a race, quicker witted, more honest, and braver than the ordinary run of white men.” Allan Quatermain soon seconded his creator on this point: “By what right do we call people like the Zulu savages? They have an ancient and elaborate law, and a system of morality in some ways as high as our own, and certainly more generally obeyed.”

1887 saw the debut of Haggard’s Umslopogaas, “the bravest Zulu of them all,” in Allan Quatermain. Five years later, urged by his friend and one-time collaborator Andrew Lang to consider “how delicious a novel all Zulu, without a white face in it, would be!” he produced Nada the Lily, an origin story for Umslopogaas and an effort to climb Mount Shaka, “to set out the true character of this colossal genius and most evil man, — a Napoleon and Tiberius in one.” Haggard biographer Morton Cohen avers that “Almost every tale of wild adventure in strange lands that appeared after King Solomon’s Mines — and they appeared by the hundreds — showed the Haggard stamp” and that “Zulus could not be otherwise than Haggard pictures them.” Charles Saunders is quite aware of all such predecessors, and if he follows in trespassing footsteps, it is to leave his own imprint and make his own mark.

As for the Crushing of which his Shingane and Nongkwaze are the twin epicenters, Donald R. Morris in his The Washing of the Spears: The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation (1965) memorably refers to the hints of hecatombs in the interior provides by the occasional “spatter of wreckage” from “the seething cauldron of humanity.” These events, from which, unlike Rwanda in 1994, no victims or victimizers survive, were just begging to be fantasticated (but not dehumanized) as Sword-and-Sorcery; Stephen Taylor emphasizes that “The new warlords sought to instill awe among their followers, respect among their allies, and to strike fear into their foes. Zwide — the one who crouches over people so that they may be killed’ — made it known that his mother’s hut was decorated with Dingiswayo’s skull. Matiwane reveled in the isibongo of “the gwalagwala bird who reddens his mouth by drinking the blood of men.”

Perhaps, having noted the poltergeisty presence of the Xhosa bovicide, Shaka’s assegais, and the gone-but-not-forgotten “Slaves of the Giant-Kings” in the Imaro series, we can also cite an example of Saunders’ work being enriched in less sanguinary fashion. The tribally-ostracized, self-exiled Ilyassai is an “African” hero created by an African-American fantasist. The relevance (to use a word hideously overused in the era that saw the character’s inception) of Imaro’s situation in terms of the demographic deformations of too many families might be best addressed by an African-American commentator, but the resonance of that situation in terms of Africa’s much-denied-or-denigrated history is obvious. Imaro makes his way as the “son-of-no-father”; until scant decades ago Africa was considered to be a continent with no patrimony to call its own. To be fatherless is to be bereft of heirlooms or heritage, and thus ahistorical. Until the final chapters of Bohu, Imaro doesn’t know where he came from; Africans were misrepresented as not coming from anywhere at all, in the sense that “”coming from” implies progress or advancement. And with no intent whatsoever of preempting or slighting the variegated political opinions held by visitors to this site, a climactic scene in which Imaro strives to drive his burning resentment inward — to cauterize his defining wound — reads a little differently these days, following a history-accelerating night in November of 2008 and a noon-time ceremony in January of 2009:

You are nothing, you are nothing, you are nothing, you are nothing, the past cried desperately.

That is a lie, said the present.

The present ripped at the past. The past fought back with insidious tenacity. But the present tore the past into shreds that died in acrid puffs of smoke against the blazing fire of his renewed soul.

Soul-renewal is something all of us can always use.

Don’t think of the Imaro novels as homework, but don’t think of them as hackwork either. Among other things they’re an opportunity to meet new monsters; one of Bohu‘s high points introduces anthropomorphic but anthropopagous creatures on loan from Zulu mythology:

For the izingogo were, as Majnun had said, human quadrupeds. Their size approximated that of a full-grown man. but the proportions of their limbs were different. Their arms were longer, ending in broad, spatulate hands. Legs bent like those of a hare propelled the izingogo in bounds of terrifying speed. Their backs were hunched like bows and their bodies, lean as a cheetah’s, were covered with short, wooly hair.

But it was the faces of the izingogo that were their most frightening feature. Save for a slight protrusion of the jaw, those faces were fully human. But when they opened their mouths, the izingogogo‘s jaws revealed the teeth of a carnivore. Those teeth and the strength of their splayed hands were the only weapons the izingogo needed other than their numbers…

Bohu himself ranks as an example of value-for-pagecount with Xaltotun, who isn’t in all that many scenes in The Hour of the Dragon, but doesn’t need to be. His face “forever hidden by a spell of darkness,” his innermost mental sanctum defiantly defended against his masters, Bohu’s is the most interesting relationship of an insubordinate subordinate to his sorcerous supervisors since Khemsa and the Black Seers of Yimsha. His second-guessing of his taskmasters, his discontent, his apparent desire, as one who will have neither the opportunity to reign in the hell of the Mashataan nor to serve in the relative “heaven” of the Cloud Striders, for Something Else — all these make him perversely attractive.

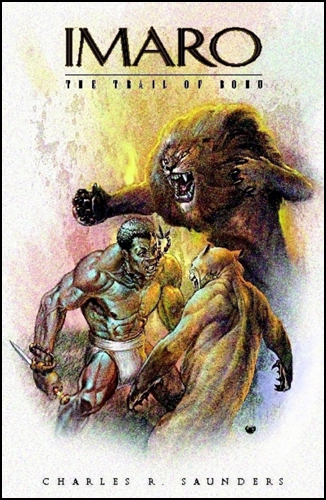

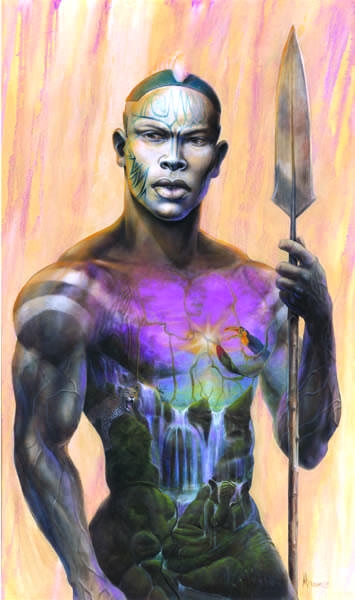

He didn’t make the new cover of the novel named after him; let’s hope artist Mshindo Kuumba is holding him in reserve for next time. Of the six Imaro cover paintings (three DAW, two Night Shade, and one Sword & Soul Media), the most swordly and sorcerous, the only one to depict the warrior battling a demon or monster, is also the worst, Ken Kelly’s for the original DAW Imaro in 1981. Every single person I’ve ever shown that artwork to has opted for a joke about Imaro’s Miles Davis hairstyle or one about Kelly’s oddly Sesame Street-ready hippopotamian antagonist.

I’ve been able to retain a sense of humor, and a bruise-empurpled optimism, about the delayed arrival of George R. R. Martin’s A Dance with Dragons in part because Bohu left me in a Trance with Lions for over two decades — not only plot-threads but also all of us who have read, and re-read, the first three novels were left hanging, left twisting slowly, slowly in the icy wind blowing off the fantasy industry’s cold-shouldering of Sword-and-Sorcery. The continuation and culmination was so near, and yet so far; so written, and yet so unavailable for reading. I would long since have hired the Watergate plumbers to get hold of the manuscript for me were it not for their advancing years and the fact that they were always somewhat less accomplished burglars than Bilbo Baggins.

The Trail of Bohu was always only half of a greater story, and if the third Imaro novel at times reads like a prologue, or travelogue, the fourth will not. Next time, we leave the DAW years behind. Next time, we go from the old being made new again to the new being made available at long last. Next time, all the fleets and armies and marauding swarms set in motion during Bohu are going to reach their destinations. Next time, we traipse through the Gates of Dream and into a region benevolently ruled by triumvirs, a radiant, wish-fulfilling trinity consisting of three words: Never. Before. Published.

And, really, after all these years something just has to be done about Bohu. That mama-mfuka got to be got.