Anima Crackers

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

posted by Steve Trout

Print This Post

Print This Post

From the very beginning of his career, up to the very end, Robert E. Howard wrote stories that involved a man and a woman and a third force that had to be overcome before they could be together. The man, strong and often dark, was Howard’s projection of his self to some extent, and the woman, often blonde, was a projection of his anima, the standard version involving a feminine aspect. From the early days of “Spear and Fang” and “The Hyena” to later works like “Red Nails” and the novelized GENT FROM BEAR CREEK, this “boy meets girl, boy loses girl temporarily to dark menacing Other, boy wins girl” story line appears quite frequently. The dark menacing Other is the shadow. But as has been pointed out by critics like Leslie Fiedler and Richard Slotkin, an unusual aspect of American classic literature is the frequency with which the dark menacing Other becomes the anima; or takes its place.

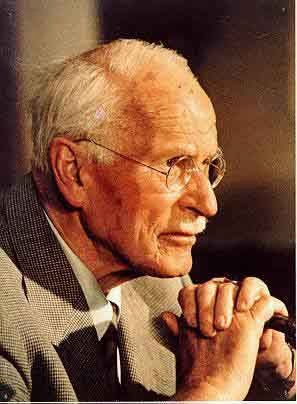

Carl Jung wrote that man has woman spiritually and physically keyed into his basic nature, just as air and food and water are keyed into his being — he is hard-wired, or programmed, to expect these things to exist, in fact cannot survive if they do not. The anima is both the soul-mate that man is looking for, and his feminine side (the “internal other”) — what he expects his woman to be, based on his own experience.

Jung also was the first to note that fantastic literature offered examples of his archetypes, asserting that H. Rider Haggard’s popular creation Ayesha, also known simply as “She”, was a fictitious example of the anima type.

In his ground-breaking piece for REHupa 100 (“Journey Inside: the Quest of the Hero in Red Nails”), Rusty Burke suggested that Valeria represented Conan’s anima, and that Howard was using this story to deal with the integration of the Self — in Jungian terms, coming to grips with sexual maturity, resulting in the integration of what are essentially severed halves, and the completion of a healthy personality. In this he echoed Weird Tales reader Reginald Pryke, who in the October 1937 Eyrie commented that he thought that in Valeria, Conan had “found at last his mate, his long-sought-for companion.”

There are some good reasons for considering Valeria to be an anima figure:

- There is generally a special kind of radiance associated with this archetype– for instance, in film, the anima is usually represented by an actress who glows — who has “star quality”, like a Monroe or a Garbo. Valeria has “lights like the gleam of the sun on blue water dancing in her reckless eyes” and her hair is “golden”.

- A focus on emotional connection — in this case, a negative focus at first, but one which Conan slowly chips away at until she becomes comfortable with the idea of him as mate.

- An origin outside of the normal setting of the story — in this case, a pirate who we are told does not belong in the forest, but “should have been posed against a back-ground of sea-clouds, painted masts and wheeling gulls.”

- A mirroring of traits seen in the male in question — her capacity for swordplay and violence, and her celebrated status mirrors Conan’s.

- A vivid zest for life.

- Offers advice to the male, sometimes quite critical, which makes him rethink his behavior. I think comparing Conan’s amorous advances to those of a stallion fits here.

Although, as noted, Howard used the feminine anima from the beginning, Valeria is probably the major female character in the major canon, and one of the best-realized and legitimate, that is, truly feminine, amina figure.

Dan Stumpf wrote a piece in The Dark Man #1 suggesting that Howard had problems with watching his mother die that he simply could not work out, but which appeared as recurring elements in his fiction. It seems that something similar may actually be a national phenomenon.

Rick McCollum’s essay on “The Valley of the Worm” in THE FANTASTIC WORLDS OF ROBERT E. HOWARD, subtitled “A Gathering of Howard’s Essential Creative Themes”, notes the relationship between the Aryan hero Niord and the brutish Pict Grom, but did not treat this inter-racial male-bond pairing as a Howard creative theme in its own right. For that insight we must turn to the unfortunately named “Come Back To Valusia Ag’in, Kull Honey: Robert E. Howard And Mainstream American Literature” by Marc A. Cerasini. Cerasini’s essay, which appeared in the 2nd The Dark Man, is in direct reference to Leslie Fiedler’s somewhat infamous essay on Twain’s HUCKLEBERRY FINN, called “Come Back To The Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey”.

The heart of Fiedler’s essay is that a special male bonding — chaste, platonic — is seen not only in HUCK FINN, but many major pieces of American literature, most notable Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales, Melville’s MOBY DICK, Faulker’s “The Bear”, and Poe’s “THE NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM”. This kind of pairing is prevalent in much pulp fiction, movies, and TV as well — think The Lone Ranger and Tonto, Miami Vice, even Star Trek.

Cerasini shows a much greater grasp of Fiedler’s essay than many critics, but when he suggests that Howard’s use of this paradigm puts him squarely into the mainstream of American letters, he is reckoning without the fact that Fiedler is widely derided, not accepted.

An example of this is seen in Phillip Rahv’s 1964 New York Review of Books piece in which he asserts (on what evidence, I have no idea) that the editors at Partisan Review originally took “Come Back to the Raft” as “a spoof on academic solemnity”. He concludes that what he calls “the race-sex thesis” (“the dream of a great love between white and colored men”) and the contention that “repressed or sublimated homosexuality is the inner secret of the American novel” are “too prankishly childish to be worth serious examination.”

Fiedler himself responded by complaining of the “shocked and, I suspect, partly willful incomprehension” his piece received. This is a bit disingenuous, for while he did note the chasteness and non-perverse form of these male bondings, he did use highly charged words like “homosexual” and “homoerotic” to describe them, and used a needlessly provocative title. It is true that Jim does call Huck “honey” a time or two, and even wears a dress at one point, but there is really nothing to suggest an other-than-innocent bond. Jim is Huck’s friend, servant, and caretaker in a hostile world. Fiedler seems incapable of using a term like “comradeship” or “sibling love” when he can use “innocent homosexuality” or “unconsummated incest” instead. Since Howard used both these themes (male comradeship in numerous stories in the James Allison, Solomon Kane, and Kull stories in particular, brother-sister love in “Dermod’s Bane,” and a few others) I abhor Fiedler’s choice of terms here.

Some critics will never accept Fiedler simply because, like Northrup Frye and Richard Slotkin, he tries to use Jungian psychiatry and a Joseph Campbellian approach to archetypes to define a mythic, uniquely American consciousness found in our literature. Others reject him for the (rightfully considered unproven) assertion about “the dream of a great love between white and colored men” being a keystone.

I think this part of Fiedler’s work can only be salvaged with a revision. I would remove all references to homosexual love, chaste or otherwise, and simply say the underlying feeling is guilt and regret, a grudging acknowledgement that the white American did great harm to the black man and the Indian, who are actually people after all, and that the white American still holds much of the blame for their current plight. Larry Richter made this comment in a long-ago InterNet discussion:

“For the white man who already has the power of science and scheming, it’s a parable for finding the power of mystery and emotion. Cold rationality, cold technology, and cold disdain find brute strength, blood lust, hate, and magic, and the thus created full hand takes the pot.”

In a non-sexual way, the dark Other completes us — that is why Jungian critics like Fiedler see them as anima figures.

D. H. Lawrence, in “Studies in Classic American Literature”, wrote:

“True myth concerns itself centrally with the onward adventure of the integral soul. And this, for America, is Deerslayer. A man who turns his back on white society. . .. An isolate, almost selfless, stoic, enduring man, who lives by death, by killing, but who is pure white.

You have there the myth of the essential white America. All the other stuff, the love, the democracy, the floundering into lust, is a sort of by-play. The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.”

Yet somewhere in the deep recesses of that stoic killer, there is a small part that wishes it could soften, perhaps. If you wish to describe an impossible dream of a great, male-bonding love between the races, I think the only appropriate context is that of Christian love. “Love your brother”. “Love your neighbor as yourself.” “Forgive those who have sinned against you.” Christian tenets still dominate, as they always have, a great deal of the white American’s thought. And white America knows it has not dealt with darker races in a Christian way, even as it has resisted the acceptance of the essential humanity and brotherhood of other races. It is the ideal of Christian love and forgiveness, however improbably, that the American soul subliminally seeks. I think this is at the root of the inter-racial pairing which does show up inordinately in American culture, and this represents something of a huge blind spot in Fiedler’s work, even for a Jewish critic with a background in Marxist criticism.

Fiedler reworked his original essay into the larger text of LOVE AND DEATH IN THE AMERICAN NOVEL, and it has some additional points that bear on Howard. First, he suggests that the darker partner in the archetypal pairing of white man and other typically bears some evil stigmata in his outward appearance. He cites the skull painted on Cooper’s Chingachgook’s chest, and the scalps on his belt, and the horrid tattoos Melville’s Queequeg carries, along with his shrunken head and pagan idol as examples.

Or the unprepossessing signs may be otherwise physical in nature, as in Poe’s description of Dirk Peters from THE NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM OF NANTUCKET (1850):

This man was the son of an Indian squaw of the tribe of Upsarokas, who live among the fastnesses of the Black Hills, near the source of the Missouri. His father was a fur-trader, I believe, or at least connected in some manner with the Indian trading-posts on Lewis river. Peters himself was one of the most ferocious-looking men I ever beheld. He was short in stature, not more than four feet eight inches high, but his limbs were of Herculean mould. His hands, especially, were so enormously thick and broad as hardly to retain a human shape. His arms, as well as legs, were bowed in the most singular manner, and appeared to possess no flexibility whatever. His head was equally deformed, being of immense size, with an indentation on the crown (like that on the head of most negroes), and entirely bald. To conceal this latter deficiency, which did not proceed from old age, he usually wore a wig formed of any hair-like material which presented itself- occasionally the skin of a Spanish dog or American grizzly bear. At the time spoken of, he had on a portion of one of these bearskins; and it added no little to the natural ferocity of his countenance, which betook of the Upsaroka character. The mouth extended nearly from ear to ear, the lips were thin, and seemed, like some other portions of his frame, to be devoid of natural pliancy, so that the ruling expression never varied under the influence of any emotion whatever. This ruling expression may be conceived when it is considered that the teeth were exceedingly long and protruding, and never even partially covered, in any instance, by the lips. To pass this man with a casual glance, one might imagine him to be convulsed with laughter, but a second look would induce a shuddering acknowledgment, that if such an expression were indicative of merriment, the merriment must be that of a demon.

There is much similarity here with Howard’s description of Grom and Grom’s people from “Valley of the Worm”:

I will take up the tale at the time when we came into jungle-clad hills reeking with rot and teeming with spawning life, where the tom-toms of a savage people pulsed incessantly through the hot breathless night. These people came forth to dispute our way–short, strongly built men, black-haired, painted, ferocious, but indisputably white men. We knew their breed of old. They were Picts, and of all alien races the fiercest. We had met their kind before in thick forests, and in upland valleys beside mountain lakes. But many moons had passed since those meetings.

I believe this particular tribe represented the easternmost drift of the race. They were the most primitive and ferocious of any I ever met. Already they were exhibiting hints of characteristics I have noted among black savages in jungle countries, though they had dwelt in these environs only a few generations. The abysmal jungle was engulfing them, was obliterating their pristine characteristics and shaping them in its own horrific mold. They were drifting into head-hunting, and cannibalism was but a step which I believe they must have taken before they became extinct. These things are natural adjuncts to the jungle; the Picts did not learn them from the black people, for then there were no blacks among those hills. In later years they came up from the south, and the Picts first enslaved and then were absorbed by them. But with that my saga of Niord is not concerned.

We came into that brutish hill country, with its squalling abysms of savagery and black primitiveness. [. . .]

His name was Grom, and he was a great hunter and fighter, he boasted. He talked freely and held no grudge, grinning broadly and showing tusk-like teeth, his beady eyes glittering from under the tangled black mane that fell over his low forehead. His limbs were almost ape-like in their thickness. He was vastly interested in his captors, though he could never understand why he had been spared; to the end it remained an inexplicable mystery to him. [. . .]So Grom went back to his people, and we forgot about him, except that I went a trifle more cautiously about my hunting, expecting him to be lying in wait to put an arrow through my back. Then one day we heard a rattle of tom-toms, and Grom appeared at the edge of the jungle, his face split in his gorilla-grin, with the painted, skin-clad, feather-bedecked chiefs of the clans. Our ferocity had awed them, and our sparing of Grom further impressed them. They could not understand leniency; evidently we valued them too cheaply to bother about killing one when he was in our power.

And our initial introduction to Solomon Kane’s blood-brother, N’Longa, shows his appearance is not one to inspire confidence:

“[T]wo eyes glimmered at him from the darkness. . .Now a form took shape [. . .] This man [. . .] was lean, withered and wrinkled. The only thing that seemed alive about him were his eyes, and they seemed like the eyes of a snake.

The man squatted on the floor of the hut, near the doorway, naked save for a loin-cloth and the usual paraphernalia of bracelets, anklets and armlets. Weird fetishes of ivory, bone and hide, animal and human, adorned his arms and legs.”

Notice that Grom, though a Pict and therefore white, is “primitive and ferocious”, and his people “were exhibiting hints of characteristics [. . .] noted among black savages in jungle countries” and note his ape-like features and “gorilla grin”. (Remember also that the gorilla was then thought to be a vicious and dangerous beast, not the timid and retiring beast modern science has shown it to be.) Dirk Peters, though half white, is similarly apish and his mirth recalls that of a demon. Like Chingachgook’s belt of scalps, N’Longa bears fetishes of human flesh and/or human bone along with those of animals. Yet in all of these cases, our white heroes, in a spirit of open-mindedness rarely seen outside of fiction, come quickly to embrace these men as boon companions and they prove to have stout and true hearts, if not hearts of gold.

Both Slotkin and Fiedler spend some time on fitting Melville’s MOBY DICK into their scheme of the great American theme. For Slotkin, it is the Great Hunt, a variation on the initiation of the Hero into new life through the ritual of the hunt. For Fiedler, it is also a kind of re-birth, where the immersion of the Hero in the blood of his slain quarry is a stand-in for the plunge into and return from the underworld. He also remarks that the dark brother stands in as a midwife of sorts in the classic American theme.

For Howard, “The Valley of the Worm” is the Great Hunt story, and it contains elements related to these discussions. True, the hunt is conceived of as an act of revenge, but it is a Great Hunt nonetheless. In fact, Ahab’s hunt for the whale is no less predicated upon revenge. But other parallels apply. In Fiedler’s view, the animal in the American novel is a monstrous embodiment of natural power, which cannot be killed until “the last day”. Like Faulkner’s bear, or Melville’s whale, there is a sense that the being represents a great power of the natural world, and its hunt must be a sacred rite if it is not to be blasphemy. It is also a part of this rite that the hunter be bedecked with symbols and fetishes of the natural world; for instance, the Pequod (itself named after an extinguished Amerind tribe) is noted to be bedecked with ivory and scrimshaw decorations taken from dead whales; it is a kind of cannibal ship hunting its own kind. Niord goes this one better; he arms himself not with a fetish or symbol of the natural world, but with a truly potent force from nature, when he takes the venom of the dead monster-snake Satha to tip his arrows against the greater force of nature, the Worm. He performs various rites to signify the solemn nature of what will be his final hunt:

“At the mouth of the valley I broke my spear, and I took all the unpoisoned shafts from my quiver, and snapped them. I painted my face and limbs as the Aesir painted themselves only when they went forth to certain doom, and I sang my death-song to the sun as it rose over the cliffs, my yellow mane blowing in the morning wind.

Then I went down into the valley, bow in hand. Grom could not drive himself to follow me. He lay on his belly in the dust and howled like a dying dog.”

As noted, Grom does not participate directly in the hunt, but he is there to bear witness, and to carry Niord’s last words back to his people. And, as emphasized in the closing line, to grieve:

“And while Grom howled and beat his hairy breast, death came to me in the Valley of the Worm.”

Ahab dies because he hates the thing he hunts — so too does Niord. The Great Hunt, according to Slotkin, is the American version of Indian initation hunts, which put great stress on the love of nature, even the thing you hunt. To fall victim to hate is to fall victim. Howard’s tale of the Worm is in synch with this classic American theme as well.