Sewer Charons, Scarab Beetles, and Salieri-ism

Sunday, March 8, 2009

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

Dickens was meant by Heaven to be the great melodramatist; so that even his literary end was melodramatic. Something more seems hinted at in the cutting short of Edwin Drood by Dickens than the mere cutting short of a good novel by a great man. It seems rather like the last taunt of some elf, leaving the world, that it should be this story which is not ended, this story which is only a story. The only one of Dickens’ novels which he did not finish was the only one that really needed finishing…

Dickens dies in the act of telling, not his tenth novel, but his first news of murder. He drops down dead as he is in the act of denouncing the assassin. It is permitted to Dickens, in short, to come to a literary end as strange as his literary beginning.G. K. Chesterton, Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens

Darting come-hither glances at potential posthumous collaborators since Charles Dickens’ death in 1870, The Mystery of Edwin Drood has been completed more often than Form 1040-EZ. Dan Simmons‘ new novel isn’t just another attempt at closure and conclusiveness. Instead, Drood — the heftiness of which, as with The Terror (2007) before it, would better suit a tome intended for the bookstores of Brobdingnag than a burden to be borne by puny, hernia-prone hominids like us — plays with Chesterton’s already playful suggestions of a “melodramatic” or “strange” literary end for Dickens, of an interrupted assassin-denunciation, of the “something more” seemingly “hinted at in the cutting short of a good novel.”

Sometimes I think Harlan Ellison’s last major contribution to the fantastique, the purple-and-gold or black-and-red genres, was his part in the “discovery” of Dan Simmons. The Song of Kali (1985) so lastingly traumatized some of us that while watching Slumdog Millionaire we had to calm ourselves with reminders that Mumbai is a reassuring 1,677 kilometers away from Calcutta. Ever since that first novel, Simmons has succeeded at almost everything he has sought to do – and he has sought to do things undreamed of by even the most imaginative horror, science fiction, and dark fantasy specialists.

A particular gift has been his willingness to accept gifts from his (and every scrivener’s) betters; again and again in his work, the Muse’s most favored clients take Simmons on as a client, become for him intermediary or demiurgic Muses, Valar of sorts. They supply him with armatures – Keats and Chaucer in The Hyperion Cantos (1990, 1991), Dante and Eliot in The Hollow Man (1992), trench-poets Wilfred Owen, Robert Graves, and Siegfried Sasoon in “The Great Lover” (1993) Homer and Shakespeare in Ilium (2003) – or themselves as characters: Mark Twain in Fires of Eden (1994), Hemingway in The Crook Factory (1999). Drood concerns itself with the final five years of Dickens’ life, and the internal and external agencies that ensured said finality.

Like Robert E. Howard and J. R. R. Tolkien, Dickens is one of my favorite writers, but for me to try and describe his feats as a novelist would be like organizing a walking tour of Jupiter were that planet to prove walkable; any such endeavor is defeated in advance by sheer scale. He doesn’t come up very often at this site, because he’s in effect a bandwidth-burster, but we can at least note that in Supernatural Horror in Literature H. P. Lovecraft credits him with “occasional weird bits like ‘The Signalman,’ a tale of ghostly warning conforming to a very common pattern and touched with a verisimilitude which allies it as much with the coming psychological school as with the dying Gothic school.” HPL’s dual alliance also shows up in A Christmas Carol, the ghosts of which are didactic, yes, but winningly weird.

In addition to being the source of hundreds of cherished English language passages, the great man is the subject of another such in George Orwell’s celebrated Dickens essay:

What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens’s photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man of about forty, with a small beard and a high colour. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry — in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.

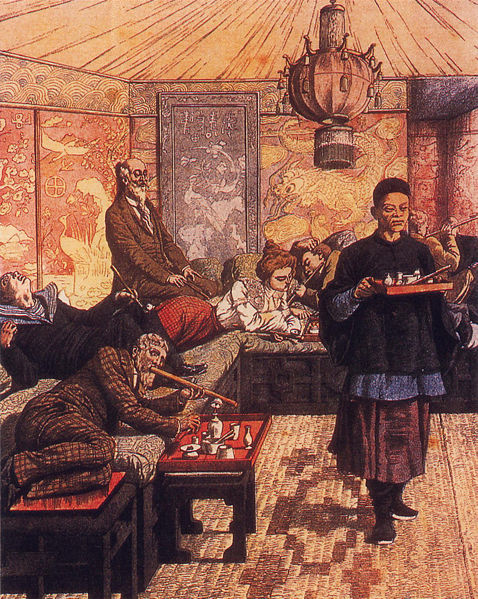

Orwell’s is not the Dickensian phiz of Drood; for starters, the author is well past forty and more selfishly set in his ways than generously angry. Just as rank has its privileges, brilliance exercises a sort of eminent domain, bulldozing the humbler hopes of family members and friends. This Dickens is hellbent on performing himself to death in reading tours with much of the hysteria of rockstardom and energy drainage almost as sinister as the psychic vampirism of Simmons’ early masterpiece Carrion Comfort (1989). More importantly, we see him through the jealousy-narrowed or opiate-dilated eyes of Wilkie Collins, for whom the older writer is a sometime mentor, publisher, and co-playwright, but a round-the-clock gall and goad. Collins is tortured by rheumatic gout and even more so by a “constant knowledge, as painful and as irrevocable as Adam’s awful awakening after being seduced into eating from the apple from the Tree of Knowledge,” that he, the lesser artist, is doomed to be drawn to, and covetous of, the greater artist’s Flame Imperishable. The title of Lillian Naylor’s Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian Authorship (2002) is if anything tactful; elsewhere, Collins has been reduced to “The Dickensian Ampersand.”

In a footnote to his annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature S. T. Joshi lists as “[approaching] the domain of the weird” the following Collins works: “The Dead Secret (1857), The Woman in White (1860), No Name (1862), The Moonstone (1868), The Haunted Hotel (1870), and the short story collections After Dark (1856), The Queen of Hearts (1859), and Little Novels (1887).” The Woman in White and The Moonstone are still read today, albeit mostly by genre-genealogists, and the writer’s attraction to at least the exurbs of the uncanny colors the contents of Drood in livid and lurid shades: “murder, death, corpses, crypts, mesmerism, opium, ghosts, and the streets and alleys of that black-biled lower bowel of London that [Dickens] always called ‘my Babylon’ or ‘the Great Oven.'” The novel even finds room for Lascars, and Lascar is not just a noun but a password, a means, like boma, kumiss, khukri, ghee, dacoit, askari, and jezzail, of entry to stories wherein midlife crises would be fripperies and colonoscopies and credit default swaps have no jurisdiction.

Interviewed by Joan Gordon for Science Fiction Studies #91 (Nov. 2003), China Miéville acknowledged “a whole tradition of ‘underground London’ books, of which Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere (1998) is probably the most well-known and successful. Partly it’s because it’s such an old city, and it’s been constructed on top of earlier layers. There are rivers that have been covered up by the city, and tunnels and construction, of which the tube (the subway trains) are a relatively recent but culturally weighty addition. Of course, the idea of things lurking around below the surface is such a potent image it’s no surprise that it features heavily in literature.” Howard and Lovecraft chipped in with the tunnels beneath London of Skull-Face and (outside the capital) the Exham Priory of “The Rats in the Walls.” Drood too explores a “terrible London beneath London”; the city that rules so much of the world cannot extend that rule to its own underworld, a domain of feral children, “Chinamen” as outrageously pulpy as the Black Scorpion Tong in the 1977 Doctor Who serial The Talons of Weng-Chiang, and others who’ve learned its labyrinth of “cellars, sub-cellars, sewers, caverns, side caverns, buried ditches, abandoned mines from some age before the city existed, forgotten catacombs and partially constructed tunnels.” Among those others may be a figure known as Drood, “a darkness in the heart of the soul’s deepest darkness” whose breath reeks of the “grave dirt and sewer-sweetness of the dead, bloated things floating in an Undertown river” and whose origins reek of the occult Egypt that made Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” so much fun.

Simmons has always excelled at the macabre, and Drood serves up rats that could swallow the alligators beneath New York City without chewing, monstrous scarab beetles of Cronenbergian invasiveness, and graveyards past which it is difficult to whistle one’s way:

Gravediggers had to leap up and down on new corpses, often sinking to their hips in rotting flesh just to force the reluctant new residents down into their shallow graves, these new corpses joining the solid humus of festering and overcrowded layers of rotting bodies below. In July, one knew immediately when one was within six city blocks of a cemetery – and there was always a cemetery nearby. The dead were always beneath our feet and in our nostrils.

But all of this is refracted through, and in crucial chapters redacted by, our narrator’s laudanum addiction. The second paragraph of Dickens’ Edwin Drood introduces us to John Jasper, whose opium dream provided the first paragraph, “the man whose scattered consciousness has thus fantastically pieced itself together.” The man telling us Drood is Wilkie Collins, whose consciousness becomes more scattered and less pieced together with each new potential overdose and each new humiliating confirmation of his literary inferiority; Dan Simmons gleefully revealed to Mary Ann Gwinn of the Seattle Times that “There’s a little, squeaky noise novelists make when they find the perfect unreliable narrator — and Wilkie was it.”

So Drood the novel and Drood the archfiend of that novel come to us courtesy of a paragon of unreliability, a memoirist who is to reportorial veracity what Bernie Madoff is to the incubation of nest eggs. Is Dickens worthy of the consecrated, canonized rest that will be his if he’s buried at Westminster Abbey? Or does he deserve not immortality but what Collins seemingly, seethingly plans, a hastened mortality and consignment to a lime pit?

I wouldn’t want The Terror a page shorter or a degree warmer, but during certain Drood chapters the reader feels as if he or she is living every last day of Dickens’ last five years alongside the great man and the wretched Collins. Simmons himself has made the inescapable comparison to Salieri and Mozart, but at least in Amadeus we weren’t awash in the acid reflux of Salieri’s soul for nigh on 800 pages. Squirmily larval where Dickens is a lepidopterist’s delight, Collins will never best the other man’s worst book even if he lives to write and rewrite well past the heat-death of the universe. That doesn’t keep him from peevishly slagging the Dickensian oeuvre to us: Little Dorrit is “a plotting disaster,” Great Expectations “a disappointment of a book, if one were to ask me,” and Bleak House “a conspiracy of auctorial incompetence wrestling with narrative dishonesty.” But then he also says of his own books “I loved none of them. They were, like my children, mere products.”

Despite its weird fiction wraparound and the fact that Guillermo del Toro has furnished both a blurb and the folding green to lock up the film rights, Drood is no The Terror or Summer of Night (1991). But the novel is as cruelly caustic a study of the throes of literary envy as master-satirist Martin Amis’ The Information (1995), save for the fact that Amis’ Richard Tull and Gwyn Barry were all his own creation, whereas Charles Dickens and Wilkie are on loan from literary history – a history that may be startled by the state they’re in when Dan Simmons gives them back.