Gunslinging Ghostbusters

Monday, February 23, 2009

posted by Steve Trout

Print This Post

Print This Post

“He was always a devil,” snarled old Job. “[. . .] The black dog! The fiend from Purgatory’s pits!”

“Well, we’ll soon see if he’s safe in his tomb,” said Conrad. “Ready, O’Donnell?”

“Ready,” I answered, strapping on my holstered .45. Conrad laughed.

“Can’t forget your Texas raising, can you?” He bantered. “Think you might be called on to shoot a ghost?”

“Well, you can’t tell,” I answered. “I don’t like to go out at night without it.”

“Guns are useless against a vampire,” said Job, fidgeting. . .

— Robert E. Howard, The Dwellers Under the Tombs

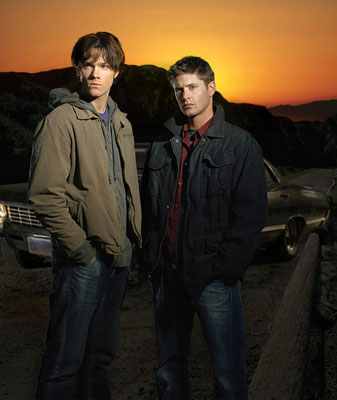

Not if you’ve got the right load, apparently. In the long-running CW series Supernatural, brothers Dean and Sam Winchester — I’m sure the name intentionally invokes both the gun-maker and the nation’s most famous haunted mansion — are quick to pull out their street-sweeper shotguns and blast away at all kinds of things ghostly and inhuman, usually with a load of rock salt. This is a play on the old idea of salt as a purifying substance, an idea common to pagan and older Roman Catholic rituals, but adds highly to the dramatic action quotient of the show. In other scenes, the brothers use salt to form a protective barrier that evil spirits cannot cross. This actually has precedent as supernatural lore, which is not always the case in this show. Later on, another famous gun-maker, Samuel Colt, becomes the source of two important plotlines, one involving a special gun that will kill vampires — and anything else.

We recently picked up the DVDs for Season One and Season Two, and watched them over the space of two weekends and a few rare Tennessee snow days. It probably worked out to a malevolent spirit being dissolved by shotgun blasts every 16-18 hours or so — never got tired of the effect, though. Sometimes, the beings they face don’t care for the touch of iron, so they use iron loads as well. Another effect used very commonly in the show is for the ghosts to move in jerky stop-motion cuts, an effect used in quite a few horror movies these days — I believe it started with Japanese movies like Ringu and The Grudge. I think the reason this effect is unsettling is that our primate ancestors, being hunters and often hunted, had to devote a lot of the brain to instantaneous vector analysis — the same skills we use nowadays to catch a football or safely navigate a left turn. It is against the norm that we are hard-wired to expect for something to move from one point to another without crossing the space between — it freaks our vector-based defenses. Against such an enemy — one moving through HPL’s oft-invoked “non-Euclidean geometry” — “no can defense,” like the nonpareil crane kick from The Karate Kid.

Like The X-Files and The Night Stalker before it, the show has a smorgasbord of monsters, demons, ghoulies and ghastlies to entertain. The brothers are on the road constantly, covering uncanny USA coast to coast. Due to the age of Dean’s traveling cassette collection, the show has an 80’s soundtrack ranging from punk to pre-Silver-Bullet-Band Bob Seger to Southern mullet rock, with the latter predominating.

I’m surprised Steve Tompkin’s feet weren’t burning with eagerness — a little Blackwoods humor there — to tell you about the Supernatural episode “Wendigo” when he mentioned the show in his post about the Fear Itself episode “Skin and Bones,” which I’ve been hoping to catch ever since. Other good stand-alone episodes include “Scarecrow”, about a fertility god who requires annual sacrifices, “The Benders,” about the family of cannibal hillbillies, and “Something Wicked” which features an Eastern European witch called a “shtriga” — a word strikingly similar to “Stregoi-“, the first part of Howard’s Stregoicavar, the “Witch-town” of “The Black Stone.” The writers on this show are obvious fan-boys and girls, judging from all the movie paradigms they pilfer, from haunted asylums to invisible hook-handed killers, to creepy little girls to killer clowns, just to name a few.

But while all the episodes were good, what I enjoyed best were those which dealt with the overlying story arc that ran through both seasons, finally culminating in a two-part finale. It’s a very dark theme of long-sought vengeance against the demon that killed the mother when the younger brother, Sam, was still an infant — a quest that has consumed their father and made him a night-stalking “hunter” who insists on them following in his footsteps.

Since they seem to be making it up as they go along, sometimes the supernatural “lore” is shaky. When asked about the significance of the number 40 in “Phantom Traveller,” Dean replies curtly, “Biblical numerology. It means death.” Um, not exactly. The reason 40, as in “40 days and 40 nights”, appears so frequently in the Bible is that it is a Hebrew idiom, best translated as “an indeterminate, but pretty long time.” I think it really means something like “I counted all my fingers and toes, and you counted all your fingers and toes, and then we gave up counting.”

Sometimes, it’s almost brilliant, though, as in “What Is, and What Should Never Be.” Here the writers reconcile the Western idea of a genie as a powerful being that can grant any wish with the Near Eastern idea of a djinn as a deadly evil spirit. They do this by having the djinn induce a fantasy in its victim that makes him believe his wishes have come true, while it feeds on his life-force ultimately causing his demise. I’d be more impressed if I didn’t suspect the idea was taken from Alan Moore’s “For the Man Who Has Everything” in which Superman is stuck in a fantasy based on his heart’s desire by a sorcerous parasitic plant called the Black Mercy. In Superman’s case, he is normal and living on a Krypton which never exploded — in Dean’s case, he is normal and living in a world where his mother never died, and he never became a ghostbuster. At any rate, it’s a very poignant episode and shows the tensions within the characters very well.

Like Josh Whedon’s Angel and Buffy The Vampire Slayer, the show deftly flits between humor, horror, action and angst, and it’s well worth the time spent. Since Robert E. Howard’s ghostbuster stories get about as much respect as O’Donnell’s decision to bring along his .45 — which does turn out to be a lifesaver when the “dwellers” emerge — it’s good to see stories in a similar vein making good on the small screen.