“Lawless Speculation and Sharply Realised Detail”

Sunday, December 7, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

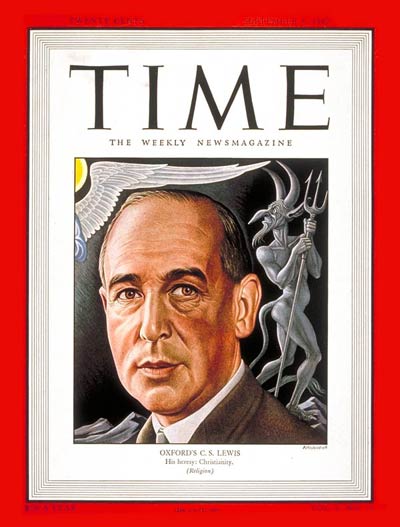

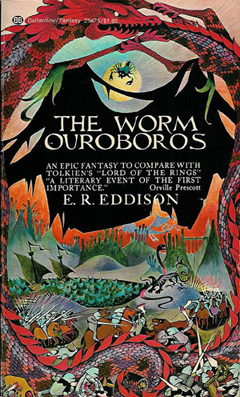

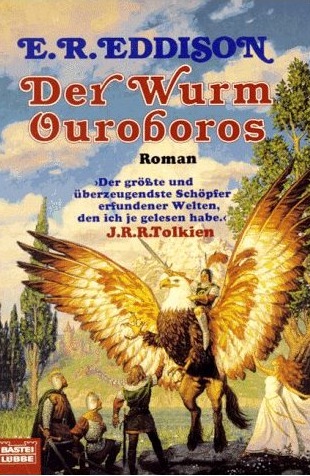

Even the Elect who revere The Worm Ouroboros may never have come across C. S. Lewis’ “A Tribute to E. R. Eddison.” Although this blurb-as-bullseye can be found in the On Stories and Other Essays on Literature collection, I’d like to quote the entire paragraph here, because Lewis makes every word count:

It is very rarely that a middle-aged man finds an author who gives him, what he knew so often in his teens and twenties, the sense of having opened a new door. One had thought those days were past. Eddison’s heroic romances disproved it. Here was a new literary species, a new rhetoric, a new climate of the imagination. Its effect is not evanescent, for the whole life and strength of a singularly massive and consistent personality lies behind it. Still less, however, is it mere self-expression, appealing only to those whose subjectivity resembles the author’s: admirers of Eddison differ in age and sex and include some (like myself) to whom his world is alien and even sinister. In a word, these books are works, first and foremost, of art. And they are irreplaceable. Nowhere else shall we meet this precise blend of hardness and luxury, of lawless speculation and sharply realised detail, of the cynical and the magnanimous. No author can be said to remind us of Eddison.

(In terms of reminding us of Eddison, had Christopher Marlowe or John Webster known, been steeped in the Norse sagas, they might have produced plays that would strike us as “Eddisonian”)

Lewis’ “lawless speculation and sharply realised detail” are exactly what I crave from fantasy, as well as the sense of a “singularly massive and consistent personality” expressing itself on the printed page. Fortunately, writers like Steven Erikson, Paul Kearney, and most recently Joe Abercrombie have appeared just in time to do for me what Eddison (and, epochally, Tolkien) did for CSL: keep my middle-aged self from being frozen in carbonite.

The rightness of Lewis’ few lines about Eddison demonstrate that much more was going on in the former’s comments on The Lord of the Rings than mere donnish solidarity or the synchronization of Inkling-watches. But is Eddison’s world (nominally Mercury) “alien and even sinister”? In a way, yes, no matter how much we’ve suited up in Homeric or Malory-supplied armor; the Worm-author represents a 20th century relaunch of the heroic temperament at its most heedless and high-handed. In this he outdoes Tolkien or even Howard; after all, to the extent that external and internal enemies permit, Kull and Conan settle into being pragmatic and progressive rulers. As much as I hanker to see Eddison’s masterpiece filmed with the resource-largesse and CGI wizardry of Peter Jackson’s LOTR films, I’m not holding my breath; while Jackson & Company did not go so far as to beat the swords of the Rohirrim into plowshares, the very idea of a warrior-people was an iffy one for them. Hence the compensatory emphasis throughout The Two Towers on refugees fleeing the Uruk-hai and the vulnerability of the women and children of the Mark. The roast-beast-fed bellicosity of Eddison’s work would have had the filmmakers on the phone screaming for Jimmy Carter.

That having been said, the antagonists of The Worm are irresistibly pittable-against one another; they elicited some of the finest descriptive passages of critic Douglas Winter’s career in his foreword to the 1991 Paul Edmund Thomas-edited trade paperback from Dell. Here he sketches those killing gentlemen Juss, Spitfire, Goldry Bluszco, and Brandoch Daha:

Valiant in war, courtly in speech and stance, these are heroes in the classical sense, superhuman, violent, passionately alive, with the ferocious good looks and fate of fallen angels; if there is a single certainty, it is that those who befriend them will die. The Demonlords are demigods who struggle for a kind of savage nobility, forever pursuing a sentimental, romantic code that places word before deed, deed before dishonor. Their trials are many, and painted brightly with blood.

Arrayed against the Demonlords are the Witches of Carcë, purveyors of a blackness which “no bright morning light might lighten” (p. 362). Their king is the crafty warlock Gorice XII, an egromancer “full of guiles and wiles” (p. 39). Skilled in grammarie, he lurks forever in his citadel, which stands “like some drowsy dragon of the elder slime, squat, sinister, and monstrous” (p.354). At his side are his warlords: brave Corund, the bearish Corsus, the insolent Corinius, and the “landskip of iniquity” (p. 366), the renegade Goblin Gro, philosopher, schemer, and traitor by nature. No blacker and more dastardly crew of scoundrels could be found; yet Eddison’s passion for them is obvious and intense.

For decades the knowledge that I have a standing invitation to visit Gorice XII in his fortress-seat has been a consolation prize for never getting to see the inside of Barad-dûr. As for Gro, is there a more beguiling character in fantasy? Even Tolkien, otherwise leery of Eddison’s strength-worship, wrote ‘I disliked his characters, always excepting the lord Gro.” The Gray Mouser is a direct descendant, and I would wager that although the parents of Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane were Adam and Lilith, a conceptual paternity test would reveal plenty of DNA from Gro as well as Melmoth.

Winter’s notion of an author’s “obvious and intense” passion for his villains is useful in a much wider context, too. Joss Whedon was clearly enchanted by the Big Bads of Buffy‘s strongest seasons (the Master, Spike and Drusilla, Angelus, the Mayor), and at least fond of the subsequent and less well-received Adam and Glorificus. Conversely, for some of us the really unforgivable failing of the seventh volume of Stephen King’s Dark Tower series was the facile, flippant fates meted out to the Crimson King and that Dark Man in a non-Howardian sense, so powerfully introduced in The Stand and still so vivid in The Eyes of the Dragon, Randall Flagg. It can’t be said didactically enough: Be good to your baddies and they’ll be good to you.

(For a characteristically informative and perceptive article on The Worm by John D. Rateliff, click here)

Returning to Lewis, he was an eagle-eyed tale-appraiser, and I wish we had his thoughts on Eddison’s 1926 Styrbiorn the Strong, or for that matter on later fantasists like Guy Gavriel Kay, Tad Williams, George R. R. Martin, and Robert Jordan. On Stories also contains “The Mythopoeic Gift of H. Rider Haggard,” the lethally effective finish of which deserves a place in the arsenal of anyone who’s ever been moved, or forced, to defend Robert E. Howard’s heroic fantasy:

No one is indifferent to the mythopoeic. You either love it or else hate it ‘with a perfect hatred.’

This hatred comes in part from a reluctance to meet Archetypes; it is an involuntary witness to their disquieting vitality. Partly, it springs from an uneasy awareness that the most ‘popular’ fiction, if only it embodies a real myth, is so very much more serious than what is generally called ‘serious’ literature. For it deals with the permanent and inevitable, whereas an hour’s shelling, or perhaps a ten-mile walk, or even a dose of salts, might annihilate many of the problems in which the characters of a refined and subtle novel are entangled.

(“An hour’s shelling” was of course no mere idle imagery-indulgence for the World War One vet Lewis)