Long Ago, Far Away, and So Much Better Than It Is Today?

Sunday, April 27, 2008

posted by Steve Tompkins

Print This Post

Print This Post

I think it’s fair to say that during 2007 we here at TC‘s Centcom were both anniversary-minded and Tolkien-minded, but fell down on the job when it came to being Tolkien anniversary-minded. In other words, we celebrated the diamond jubilee of “The Phoenix on the Sword” and the miracle of filial piety that saw The Children of Húrin into bestselling print as a near-novelistic standalone, but we spaced on the 30th anniversary of The Silmarillion, that gateway to the First and Second Ages of Middle-earth. Unfinished (but unbeatable) tales, false starts better than the true finishes of most fantasists, and all the priceless detritus of what Tom Shippey termed “intense and brooding systematization” would follow, but the 1977 book came first — as it also did, in its earliest form of The Book of Lost Tales, in Tolkien’s creative life.

The Simarillion‘s thirty years at large in the world have played out as something of a Thirty Years War. Ted Nasmith’s painted realizations of Silm.-scenes are far more vivid than the poor-visibility-or-soft-focus efforts of certain mistier Tolkien illustrators, but he was fairly mild-mannered when he described the work as “magnificent but underappreciated.” It occasionally seems to me that Mein Kampf hasn’t been reviewed as vitriolically and vindictively as The Silmarillion. Much-purchased upon publication but anecdotally little-read, dismayingly “like the Old Testament,” “as boring as the endless legalistic pedantries of Leviticus,” “a telephone directory in Elvish,” or “a stone soup of the most mouth-mangling names ever seen in print.” One worthy speculated that someone capable of reading The Iliad “for pleasure” might just about be able to enjoy The Silmarillion — his disbelief that any such freak existed, or should be permitted to exist, was so tangible it might as well have been in Braille. The Time reviewer back in October of 1977 bemoaned the absence of “a single, unifying quest” and “a band of brothers for the reader to identify with.” As it happens The Silmarillion‘s central narrative does indeed feature a single unifying quest, and it’s the stuff of nightmares, the nightmares endured and perpetrated by a band of literal brothers hagridden by an overbold oath sworn in haste and repented at sorrowful leisure.

Many, many Tolkien fans have been unable to forgive the book for not being The Lord of the Rings. This criticism confounds me; Some Girls isn’t Exile on Main Street, and Exile wasn’t Aftermath, but so what? Hardly more receptive have been some Tolkien critics and scholars who ought to know better, read better — as initiates bask in the current golden age of Tolkien Studies it might seem like the act of an ingrate or churl to harbor a pet peeve about this, but I do. Patrick Curry’s Defending Middle-Earth: Tolkien, Myth and Modernity (1997) alternately dressed JRRT in forest green or reconfigured the reserved Edwardian and rose window Catholic as an unlikely, waistcoat-wearing shaman of postmodernism, backhanding The Silmarillion all the while because. . .no one really read it. Janet Brennan Croft’s War and the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien (2004) made skillful use of Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory, and even devoted its Chapter Three to “World War I Themes in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.” Yet Croft was comfortable ignoring The Silmarillion‘s war to end all warriors, one which spans hundreds of years and tens of thousands of casualties, and, stasis-sealed in stalemate and attrition, reminds us in every chapter of how the Western Front came to resemble a gargantuan, technologically upgraded medieval siege. Marjorie Burns’ Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien’s Middle-earth (2005) flaunted the same sin of omission. Norse and Celtic elements are as integral to The Silmarillion as are hydrogen and oxygen to water; the book is so northern that compasses point quiveringly in its direction, but Burns barely bothers with it.

Luckily, not all Tolkienists are as blinkered in this respect as Croft and Burns: of the Silm.-immersive studies I’ll mention two by Verlyn Flieger, Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World (1983, revised 2002) and Interrupted Music: The Making of Tolkien’s Mythology (2005), and what is for me the most exciting JRRT-related book of the Aughties, John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-Earth (2003). These were joined in late 2007 by Walking Tree Publishers’ The Silmarillion Thirty Years On, edited by Allan Turner, which contains Michael Drout’s “Reflections on Thirty Years of Reading The Silmarillion,” one of the best and bravest Tolkien pieces ever written. Drout is the William C. H. and Elsie D. Prentice Associate Professor of English at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, and as an academic he’s a survivor in a milieu where self-exposure might as well be indecent exposure, a wallow in the slough of subjectivity. He admits, but does not apologize for, “the exceptionally personal nature of this essay,” and the unusual approach could not be a better fit for an exceptionally personal work like The Silmarillion. The nine-year-old Drout, hard-pressed by a problematic relocation and the splintering of his parents’ marriage, collaborates movingly with the professor who’s enough of an Anglo-Saxon specialist to merit a place among Harold Godwinson’s housecarles on Senlac Hill (Stop by his blog, Wormtalk and Slugspeak, for, among other attractions, a stimulating discussion of when Beowulf came into being, with choices like Migration Period, Conversion Era, Golden Age, Viking Raids, Reform, or Anglo-Danish Rule)

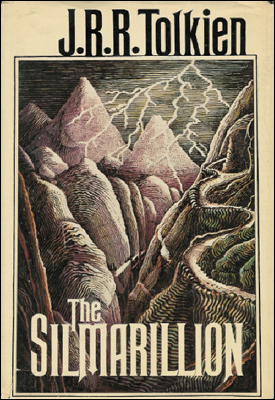

Some of the appeal “Reflections on Thirty Years of Reading The Silmarillion” holds for me has to do with experiential overlap. Drout writes “Waiting for me under the Christmas tree that year [1977], a gift from Santa Claus mixed in among the various Star Wars toys my brother and I had coveted, was a copy of the book, the cover illustrated with a colorized version of Tolkien’s drawing ‘The Mountain-path.'” Same deal in the Tompkins household, and the Christmas mass we attended that morning, after the presents had been unwrapped but before serious enjoyment could begin, was the draggiest, most temporally distorted I ever endured.

Drout was new to my native region at the time: “We had been used to living on the ninth floor of a high-rise building in New York City, where having enough heat was never a problem (too much heat was), so it was very difficult to adjust both to the new frugality brought on by the energy crisis and the typical New England approach to keeping houses chilly. ” For me it was the opposite; that just-shy-of-cryogenic “New England approach” was the norm, and the flamethrowerish blasts of heat typical for New York City buildings almost killed me when I went off to college. The Great Blizzard of February 1978, which lives in New England folk-memory thanks to winds that threw their weight around like hurricanes and civilization-canceling accumulations that sneered at the best efforts of snowplows, snowblowers, and the National Guard, serves a backdrop to Drout’s essay. He plunges back into his most prized Christmas present while “it [is] easy to feel as if Morgoth was winning, as if the bitter cold we all felt was rushing out of the gates of Angband.”

Morgoth (the first and infinitely more powerful of Middle-earth’s two Dark Lords) is indeed winning for chapter after chapter after chapter. The Silmarillion is more of a downer than the average bottomless pit; Ted Nasmith paintings like “The Kinslaying at Alqualondë,” “Flight of the Doomed,” “The Hill of Slain,” “The Burning of the Ships,” and “Finduilas Is Led Past Túrin at the Sack of Nargothrond” hint at what readers should expect. Drout quickly confronts the fact that as compared to LOTR, the constituent texts of The Silmarillion are “far more unforgiving, close engagements with death and entropic destruction, the theme (as Tolkien put it in ‘Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics’) ‘that men, each man and all men and all their works shall die.'” And never more so than in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, of which Drout recalls: “My favorite part of The Silmarillion that year was Chapter 20: “Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad,” nine pages of almost unmitigated disaster poured upon all the heroes of the previous chapters.” The Eldar, The Fair Folk, Tolkien’s supposedly spoiled darlings, bring this on themselves. Here it might be most efficient to quote the Prophecy of the North, the curse Mandos, the Doomsman of The Silmarillion, launches like a salvo of cruise missiles at the rebel Elves:

Tears unnumbered ye shall shed; and the Valar will fence Valinor against you, and shut you out, so that not even the echo of your lamentation shall pass over the mountains. On the House of Fëanor the wrath of the Valar lieth from the West unto the Uttermost East, and upon all that will follow them it shall be laid also. Their Oath shall drive them, and yet betray them, and ever snatch away the very treasures that they have sworn to pursue. To evil end shall all things turn that they begin well; and by treason of kin unto kin, and the fear of treason, shall this come to pass. The Dispossessed shall they be forever.

(Dispossession, the import of which keens like a coronach through so much modern fantasy, was a Tolkien specialty) And so it goes; here is Drout’s casualty report:

But even “hard-hearted” would be a litotes for describing the way Tolkien treats his characters in The Silmarillion: Miriel, Finwë, Fëanor, Aredhel, Eöl, Angrod, Aegnor, Fingolfin, Fingon, Beleg, Orodreth, Gwindor, Thingol, Celegorm, Curufin, Caranthir, Dior, Nimloth, Turgon, Glorfindel, Amrod, Amlas, and Maedhros are all killed by violence or by wasting away, and those are merely the main Elves who die.

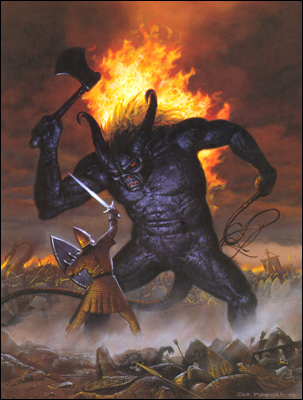

If that reads like the premise for the most engrossing Icelandic saga never written, it isn’t a coincidence. Bloodlines and bloodfeuds often elbow individual characters aside as the protagonists of The Silmarillion. Few of the Elves survive a sufficient number of pages for much to be achievable in the way of characterization, but they are at their most human, which is to say fallible and culpable, throughout. Fëanor, who crafts both the Silmarils and the outrages that lead Mandos to pronounce sentence, is if not a black Prometheus like KEW’s Kane, then certainly a crimson one, a pyrotechnic event. Although he scorns Morgoth with the most Shakespearean diss in the whole fantasy genre (“Get thee gone from my gate, thou jail-crow of Mandos!’ And he shut the doors of his house in the face of the mightiest of all the dwellers in Eä”, Fëanor actually recapitulates the artistic/demiurgic imperative that motivates Morgoth when, in his original guise of Melkor, he is present at the Creation, the heights and depths to which genius can be spurred. “Love not too well the work of thy hands and the devices of thy heart” might be The Silmarillion‘s cardinal warning, which Fëanor ignores. Tolkien tells us that he is “consumed by the fire of his own wrath,” and indeed he dies “wrapped in fire and wounded with many wounds” — the Balrogs who bring him down in effect fight fire with fire.

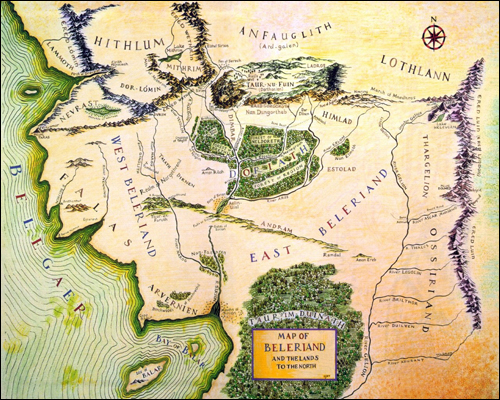

Of the lordly Thingol Tolkien writes “Wide were the countries of Beleriand, and many empty and wild, and yet he welcomed not with full heart the coming of so many princes in might out of the west, eager for new realms” — this Elvenking could almost be the emperor Alexius, fretting at the arrival of the First Crusade. And yet, through the application of what Christopher Tolkien described as a “characteristic tone, melodious, grave, elegiac, burdened with a sense of loss and distance in time,” a terrible beauty is born, if the reader consents to sup his fill of sadness.

Sadness is of course a thoughtcrime in the U.S. of A., even more of a hanging offense than not wearing a flag lapel pin. It is in “defense” of this alien and seditious emotion that Drout says certain things about as well as anyone ever has: “If sad things happen to them, people will be sad, and there is nothing abnormal about it and nothing to be done beyond waiting for the sadness to pass. Sadness is a part of being human. It is not something to be cured or treated.”

From sadness Drout proceeds to a sister-feeling:

Once we recognize the inevitability of death and loss, we are, I think, ripe for nostalgia, a feeling that has been (perhaps deliberately) misunderstood as a kind of tedious affectation, the indulgence of an old man endlessly talking about the great days of his youth. That stereotyping is the trivialization of a very central human emotion, and nostalgia is far more significant than its bad reputation would indicate.

Nostalgia is, in fact, as natural a response to time’s unidirectionality as are antibodies to pathogens:

War, famine, death of one’s lord, the commission of crimes: these things all could lead to that condition most horrible to the Anglo-Saxons, exile. But there is another kind of exile as well, one that is forced upon all individuals, not just the guilty and the unlucky: that is the exile from one’s past that is created by the forces of time. Time pushes relentlessly into the future, separating us further and further from childhood, then from youth, and all the while from those whom we have loved.

Every paradise is lost, that’s what paradises are for. The angel with a flaming sword is essentially supernumerary; all that mortals can ever do with a paradise is lose it by evicting and exiling themselves. And we are most of us therefore susceptible to the same temptation that animates Xaltotun as much as does the Heart of Ahriman in The Hour of the Dragon: look homeward, malign angel. But when the Noldor, the self-propelled outcasts of The Silmarillion, look homeward, a special and arguably sadistic refinement comes into play, as Drout points out: “The Elves do not merely remember their past as perfect; it still exists, across the seas, in Valinor and Tol Eressëa, and the actual existence of this paradise makes their separation all the more poignant.” We humans aren’t as lucky (or is it unlucky?) as Tolkien’s Elves, but Valinors of sorts are available to us, be they the green-gold stun grenade of a spring day, the Polaroid poignance of that one page it might be easier to skip in the photo album, or a chance hearing of a long-ago hit single that ruled the airwaves all during one of those cusp-between-adolescence-and-adulthood summers when possibility and probability were still in equipoise.

Few supervillains have ever rivaled Morgoth in the creation of nostalgia through “the destruction of every beautiful city (Menegroth, Nargothrond, Gondolin). The silmarils are lost and Beleriand is in ruins.” Coming to The Silmarillion from an Iliadic background, this urbicidal emphasis mesmerized me (If I’m not careful, I can even lapse into pining for purple-towered Python); it was like watching jackboots smashing a succession of the most ornate dollhouses and elaborate dioramas ever created. Drout stresses that eucatastrophes (Tolkien’s coinage for climactic, predicament-dissolving mega-events like the Incarnation or the providential completion of Frodo’s mission) are scarce in the book:

Tolkien may have intended the War of Wrath to be one, but the chapter as it stands, perhaps because it happens mostly in very swift, skeletal narration, has a very different emotional effect than the horns of Rohan. Perhaps this eucatastrophe (the hosts of the Valar arriving from the West) is diminished in The Silmarillion because the price paid for it, the undercutting of the victory, is given more narrative space than the victory itself: the theft of the silmarils by Maedhros and Maglor, and the eventual loss of the jewels makes much of the war seem as if it was fought for naught. But for me this does not diminish the power and the beauty of The Silmarillion, quite the opposite.

(While it is as silly to look for isomorphism between World War One and The Silmarillion as it is between LOTR and World War Two, a longstanding complaint among the Blimpish who still lobby for a more old-fashioned, patriotic, it-was-worth-it treatment of the Great War is that the Allied victories in the titanic battles of the summer and fall of 1918 have always had far fewer books, or pages within books, devoted to them than the butchershop bungles of 1915-1917. And just as everyone who has read about 1918 after 1939 has done so knowing that it would all need to be done over again, everyone who comes to The Silmarillion from Rings knows that the Free Peoples are going to have to do it again, with unnervingly less overseas assistance, against the next Dark Lord.)

“A work of art can do more than comfort or encourage or distract or console,” Drout reminds us. To harrow is the legitimate function of a few black-beaked works; the lack of overt consolation can be perversely consolatory for certain sensitivities. Drout writes “Tolkien’s world has provided a master narrative, the workings out of a pattern of building and loss, triumph and fall, beauty and wreckage, that seems to me to lie beneath all of human history, both the immediately personal histories of individual lives and the vast sweep of peoples and nations.” This talk of “a master narrative” and “the vast sweep of peoples and nations” summons more than just The Silmarillion and the appendices to The Return of the King; “The Hyborian Age” is right there with them, which is why I cling to the minority opinion that the exclusion of Howard’s pseudo-history from both Skull-Face and Others and last year’s two-volume The Best of Robert E. Howard was wrongheaded and shortsighted. And Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane stories owe much of their brutal power to the fact that we witness the vast sweep, the triumphs and falls, the beauty and wreckage, through the unmeetable blue eyes of a single accursed actor.

“For Tolkien, the answer to these tragedies of being human was his religion, but for people who lack his gift of faith, there may be no consolation, merely acceptance: but that can be almost enough.” To which I would add, almost enough if fictional but heartfelt tragedies are presented artistically and cathartically. Guy Gavriel Kay assisted Christopher Tolkien in assembling The Silmarillion for a year, and it’s no coincidence that his own epic fantasies The Fionavar Tapestry and Tigana also manage the feat with which Drout credits the 1977 book, to “shape grief and loss and fear into order and beauty.”

Aeschylus poor-mouthed his plays as “slices from the great banquet of Homer,” and however much I dote on it, The Children of Húrin exists in a similar relationship to The Silmarillion. As Christopher Tolkien revealed back in 1977:

To bring [The Silm.] into publishable form was a task at once utterly absorbing and alarming in its responsibility toward something that is unique. To decide what that form should be was not easy; and for a time I worked toward a book that would show something of this diversity, this unfinished and many-branched growth. But it became clear to me that the result would be so complex as to require much study for its comprehension; and I feared to crush The Silmarillion under the weight of its own history.

Although the younger Tolkien has since been hard on himself in second-guessing the many decisions he was forced to make with his father’s drafts spread out on a Procrustean bed, far from being crushed, The Silmarillion is now perched gloriously atop its own complex history. To which we bring histories of our own; all honor to Michael Drout for sharing his, and prompting reflections that without this one book, the past thirty years would have been more like a garbage scow than an argosy, a shotgun shack than a Gondolin or City of Wonders.

The Internet teems with would-be trailers or pre-vis pitches for a filmed Silmarillion; here’s one scored to the great Howard Shore getting his Wagner on. The artwork varies wildly in quality (thank the Valar for Nasmith), but over the course of seven minutes you get a sense of how the master narrative passes “from the high and the beautiful to darkness and ruin,” for “that was of old the fate of Arda Marred.” Perhaps it’s the fate of any Arda we can ever hope to know.